ON A SUMMER DAY in Zambia’s capital, Lusaka, I stood by helplessly as a young woman struggled to communicate why she had come to the University Teaching Hospital, the largest medical facility in the country. The intensity of her pain was agonizing to watch, as it rose from her abdomen to her chest, escaping momentarily through a series of whimpers. Lying alone in a sparse, dimly lit room marked simply “side ward,” she was isolated from the other 28 beds outside the door, most occupied by women who had ventured some distance across this Southern African nation to be treated for cancer or who were simply too sick to return home between treatments.

“She is 36 and has two children, but her husband divorced her when she got sick,” Amy Sikazwe whispered to me as we crept out of the room. A breast cancer survivor since 2005, Sikazwe now works as the publicity secretary for Breakthrough Cancer Trust Zambia, founded in 2001 to educate women about early detection and prevention of breast and cervical cancer.

Sikazwe offered to take me, an 18-year survivor of breast cancer from the U.S., on one of her frequent visits to the women’s cancer ward, which Sikazwe’s organization established at the hospital in 2002.

I learned that although the nonprofit had been instrumental in providing a place for female cancer survivors to seek treatment away from home, this particular woman’s story reflected many issues that the hospital couldn’t address—including the late detection of cancer in a culture where many women fear desertion if they seek care, and patients’ poor understanding of their own medical needs or treatment.

The woman before me had cervical cancer and feared that her cancer had metastasized. But as nurses attempted to gather information from her, they realized that she had little knowledge of her medical history. Now close to death, all she could say with certainty was that she had been abandoned by her husband and might never again see her children.

The woman’s plight is a familiar one in Zambia. About 3.2 million women, ages 15 and up, live in this developing nation, where cervical cancer is the most frequently diagnosed and deadly cancer in women. Among every 100,000 Zambian women, about 53 were diagnosed with cervical cancer and 39 died of the disease in 2008. By comparison, in the U.S., cervical cancer ranks 12th in cancer incidence and 13th in cancer mortality. Among every 100,000 American women, eight are diagnosed with cervical cancer and between two and three die of it each year.

But the tide may be beginning to turn, as the severity of the cervical cancer situation has spurred Zambian and American health care professionals to collaborate on innovative ways to address the problem. Today, a multipronged effort—which takes advantage of Zambia’s existing resources and honors its traditions—is aiming to help save lives. It’s a strategy that’s not unlike anti-cancer efforts in other resource-poor countries and in U.S. communities where researchers have learned that the best approaches for one group of people aren’t necessarily the most effective ones for another community.

Cervical Cancer at Home and Abroad

Now home to a population of nearly 13 million people, the Republic of Zambia was established in 1964 when Northern Rhodesia changed its name after gaining independence from the British. Located east of Angola and bordering the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north and Zimbabwe to the south, Zambia is a diverse country. More than 70 ethnic groups bring their own languages and cultures to the nation’s fabric.

I initially left the Zambian hospital sure that the cancer challenges in Zambia are vastly different from ours at home, with cervical cancer a prime example. The progress made against cervical cancer in the U.S.—where deaths have plummeted by 70 percent since the 1940s—is one of the biggest success stories in American health care. But it’s not a story that is universal.

Since the introduction in 1943 of the Pap test, which can identify precancerous lesions on the cervix, prevention and early detection of the disease have been the norm among American women. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2008, 75 percent of American women 18 and older had a Pap test within the prior three years. And since 2006, availability of the HPV vaccine—which can prevent the viral infections that cause most cervical cancer—has promised to continue to reduce cervical cancer diagnoses and deaths in the U.S. But developing nations like Zambia currently lack the financial means and infrastructure to make Pap tests and HPV vaccination widely available.

In fact, by any measure of health and health care, the differences between Zambia and the U.S. are stark: Zambia is one of many African countries with a high incidence of HIV and AIDS, with an estimated 13.5 percent of the adult population living with the disease, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), compared with the U.S. rate of less than 1 percent. Average life expectancy among Zambians is 48 years, while Americans can expect to live an average of 79 years, according to WHO data. And infant mortality in Zambia is 69 out of every 1,000 births—10 times the U.S. rate.

So it shouldn’t come as any surprise that cancer outcomes in Zambia are poor as well. Even so, when American physician Groesbeck P. Parham, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, headed to Lusaka in 2004 to study the prevalence of abnormal Pap smears among HIV-positive women, a project funded by the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Center for AIDS Research, he and his collaborators were shocked by their findings. Of 150 women seeking or receiving anti-retroviral medications for HIV, 140 exhibited cervical abnormalities. It was one of the highest rates ever reported in a population.

“Women in resource-constrained countries like Zambia were starting to live longer with HIV, thanks to anti-retroviral therapy,” Parham explains, “but they were at risk of dying of a cancer that can be prevented through early detection with a simple Pap test.”

The data were so compelling that Parham teamed up immediately with the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia, the CDC in the U.S., Zambia’s Ministry of Health and the University Teaching Hospital to establish two cancer prevention clinics in government-run public health facilities in Lusaka in January 2006.

Parham saw it as his calling to go to Zambia and remain there to help develop a comprehensive cervical cancer prevention program. “In 2005, I made a bargain with God,” he says. “I asked him to take me and put me in a place in the world where I could serve the most dispossessed women on the planet, and if he did, I would go and stay until he told me to come home.”

Screening That Works

When Parham first told me about the screening clinics, I envisioned a scenario similar to my own annual Pap test, during which a doctor scrapes cells off my cervix and sends them to a pathology lab for analysis. But the Pap test alternative he described—which has now screened more than 65,000 Zambian women—was unlike anything I knew.

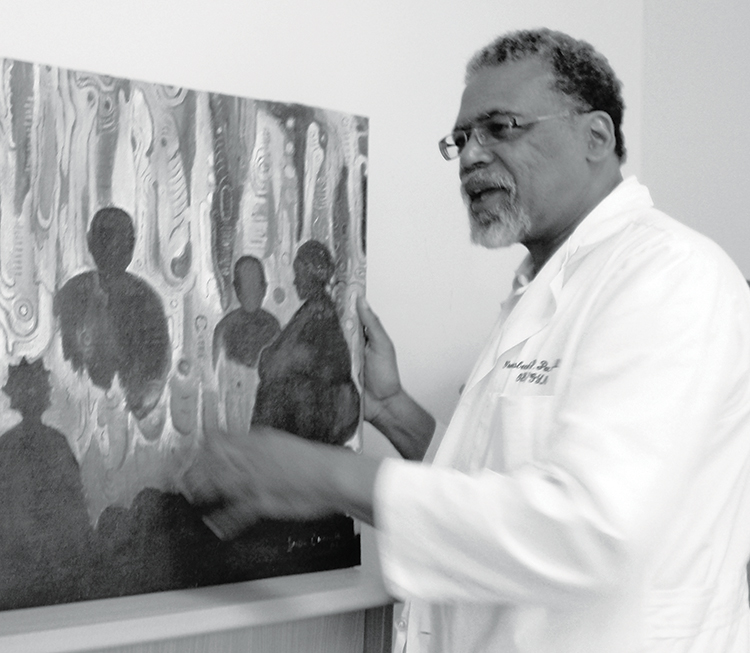

Women in Zambia were living longer with HIV, thanks to new drugs, says American physician Groesbeck P. Parham, “but they were at risk of dying of a cancer that can be prevented through early detection.” Photo by Cynthia Ryan

Parham and his colleague Mulindi Mwanahamuntu, a gynecologist at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, needed a screening strategy that was inexpensive and accessible, and that worked with the available resources of a nation that has just 15 gynecologists. The first two clinics employed two nurses, who began training others. In the last six years, the program has expanded to 18 clinics with 18 nurses in two regions.

The clinics use a low-tech screening approach known as “visual inspection with acetic acid,” or VIA, which has been introduced in a number of developing nations over the last decade. To screen with VIA, the nurses coat women’s cervixes with vinegar, which turns precancerous cells white. After taking pictures of the cervixes with digital cameras, the nurses email the photos to doctors and consult with the physicians via cell phone. The nurses can then destroy precancerous lesions during the same visit by freezing them—a procedure called cryotherapy. The plan, according to Parham, is to expand the VIA screening clinics to every one of Zambia’s nine provinces.

Accumulating evidence suggests that VIA works. In one study of women in the Tamil Nadu region of India, published in 2007 in the Lancet, an international team of researchers found that even a single round of VIA screening can significantly reduce cervical cancer deaths. In a statement issued in July 2011, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said there’s growing evidence that VIA with cryotherapy is a “safe, acceptable and cost-effective approach to cervical cancer prevention.”

In Zambia, an added benefit of VIA is that many women seem to feel more at ease when treated by a female nurse, says physician and public health specialist Sharon Kapambwe, a native of Zambia who runs the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program. “A lot of the women prefer to be seen by someone they can relate to.”

As I spoke to Parham and Kapambwe, the Zambian screening program began to remind me of cancer prevention efforts tailored to communities at home. In parts of Appalachia, for instance, fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) are being used in place of more sensitive and expensive colonoscopies for colorectal cancer screening because they are simpler, more affordable and more accessible to a rural U.S. population.

Just as FOBT may not be the gold standard for detecting colorectal cancer, IA may not be the “best” screening for cervical cancer by Western standards. But Paul Blumenthal, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Stanford University School of Medicine in California, points out that within the constraints of a low- or middle-resource country, the visual inspection method is an effective technology.

Anything you do in life has strengths, benefits, limitations,” says Blumenthal, who directs the Stanford Program for International Reproductive Education and Services and was a pioneer in the use of VIA in developing countries. “Good is never the enemy of the best.”

Effective screening and prevention strategies can be performed by trained nurses.

by Suzanne Byan-Parker

In impoverished countries, medical technologies and physicians are lacking, and patients can’t afford to travel long distances for medical visits. But researchers are now implementing effective cervical cancer screening and prevention strategies that rely on available resources, can be performed by trained nurses and avoid repeat clinic visits.

In the last decade, a growing number of nations—including Zambia, Thailand and India—have been using a procedure called visual inspection with acetic acid, or VIA. It’s an easily performed, accurate and cost-effective way to detect cancerous or precancerous cells. During the procedure, a woman’s cervix is treated with a vinegar solution, which causes abnormal cells to turn white. Trained nurses may freeze and destroy the abnormal tissue—now visible to the naked eye—during the same clinic visit.

Research suggests that a woman who is screened with VIA once in her lifetime reduces her risk of being diagnosed with cervical cancer by 25 percent.

In the future, sensitive tests for the human papillomavirus (HPV)—the virus that causes most cervical cancer—may prove even more useful than VIA. An HPV test, called careHPV, which was developed by Qiagen and the nonprofit PATH organization, is currently in clinical trials. It costs less than $5, can be self-administered and provides results in less than three hours. A trial of more than 130,000 Indian women, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2009, found that women 30 to 59 who received HPV screening were half as likely to develop advanced-stage cervical cancer or die of the disease during eight years of follow-up as women who weren’t screened.

Kitchen Parties and Alangizis

Finding technologies that work within available resources is just one component of Zambia’s Cervical Cancer Prevention Program. In order to provide information to women who might not visit a medical clinic, Parham and his colleagues have sought the expertise and collaboration of Alangizis, Zambian women who already hold positions of credibility in their communities as traditional marriage counselors.

Alangizis convey information about married life to brides through one-on-one counseling and at kitchen parties—the equivalent of an American bridal shower. When the Cervical Cancer Screening Program was being established, Kapambwe and other Zambians working on behalf of the program reached out to the Alangizis and asked them to join in efforts to educate young women in the nation’s villages. To date, Parham and his coworkers have trained more than 60 Alangizis to communicate information about cervical cancer detection and prevention to the women they counsel.

Kapambwe explains that the Alangizis can “package the message about cervical cancer, make it one of the things talked about,” in addition to advice on serving husbands, getting along with extended family, and other domestic matters. Alangizis explain the science of sexual relations, Kapambwe says, and they “are trusted to provide accurate information.”

An Alangizi’s role in spreading the message of cervical cancer prevention is similar to likeminded efforts in the U.S. that use laypeople to reach medically underserved populations. For instance, researchers from New York City, Philadelphia, Denver and Los Angeles have teamed up with the National Black Church Initiative to educate men and women about cancer through their churches. Even in my own work with homeless cancer patients in Birmingham, Ala., I’ve learned to depend on community insiders—the men and women who have struggled with cancer on the streets—to share their stories with other homeless individuals.

Just like in Zambia, I’ve found, information about cancer prevention and detection is often most effectively explained by trained members of a person’s own community, in terms they understand.

Women’s Stories

Before departing Lusaka, I had the opportunity to meet with two women in the cancer ward at the University Teaching Hospital. Both Cecilia Mumba and Joyce Musonda were completing treatment for cervical cancer, but their personal stories couldn’t have been more different.

Before she got sick, Mumba, 50, worked as a midwife in the city of Luanshya in the Copperbelt province of Zambia. After experiencing symptoms of menopause, she noticed a clot of blood in February 2010 and knew that something was wrong.

“I went to the doctor and he did an ultrasound,” Mumba told me. “There were fibroids, heavy bleeding, cramping, gushes of blood.” She asked her gynecologist to meet her at a private hospital in Luanshya. He did a vaginal exam and “knew right away that I had cervical cancer,” she recalled.

A biopsy was performed and within two days Mumba had a diagnosis: stage IIA cervical cancer. She had surgery to remove her cervix and was then admitted to the University Teaching Hospital, where she began three months of daily radiation treatment.

Articulate and self-assured, Mumba smiled when I asked about her husband’s reaction to her diagnosis and her need to stay in the cancer ward in Lusaka. “He is OK,” she said. “My husband told me, ‘This is what you must do.’ ”

“My children are worried,” Mumba continued, especially the oldest of her four children, ages 14 to 26. But she said, “I told her, ‘It will be OK, I will get treatment.’ ”

In 2002, Breakthrough Cancer Trust Zambia established the women’s cancer ward in the maternity ward at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka. Photo by Cynthia Ryan

Musonda, also 50 and diagnosed with stage IIA cervical cancer, had a different story. She spoke no English and relied on Mumba to translate. Born and raised in the Congo where she completed school through the eighth grade, Musonda moved to Luanshya when she could not make a living at home. In Luanshya, she married and gave birth to eight children. Her husband died in 2002 from complications of tuberculosis, so she struggled with her cervical cancer diagnosis on her own. “Luckily,” Musonda said, “some of my children are married and keeping my younger ones while I am here.”

Musonda experienced pelvic bleeding for several months before going to a clinic where Mumba worked as a midwife. The two had known each other for several years, and Mumba had assisted in the birth of some of Musonda’s children.

“Cecilia told me to go to hospital,” Musonda explained. Through an ultrasound, a doctor discovered fibroids in October 2009. A week later, Musonda had a laparoscopic procedure and cancerous tumors were found.

After a surgeon removed the tumors, Musonda came to the University Teaching Hospital for chemotherapy. She was now undergoing 26 days of radiation, at the end of which she would have another round of chemotherapy.

“I’m not scared anymore,” Musonda told me. “The doctor is reassuring.” Her children were frightened, though, according to Musonda. “I have explained [the situation] to them,” she added with a slight smile, “so now they have hope.”

Both Mumba and Musonda were focused on going home and getting on with their lives, but Mumba seemed to have a wider objective to accomplish. Her expression became serious when she talked about the ongoing challenge of cervical cancer in Zambia. While the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program’s efforts are a start, she doubts they go far enough. “The clinics are a good idea, but we need more of them,” she said. What’s more, “not everyone who will be married goes through an Alangizi, and girls are going through an Alangizi one at a time. We need the information in clinics, schools, churches, markets.”

As Mumba spoke, I thought back to the woman lying in pain in the side ward—just a few feet away from where we now sat. Perhaps she had been too scared that her husband would desert her or too unaware of the severity of her symptoms to seek more quickly the kind of care that Mumba and Musonda were receiving.

I returned home to the U.S., contemplating the immense obstacles facing Zambia. As Mumba so candidly expressed, efforts like the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program must be expanded significantly to reach women who live far from existing screening clinics or who do not rely on an Alangizi. Until then, Zambian women continue to be at risk for cervical cancer and are likely to be diagnosed in late stages.

Months later, I was saddened to learn that Mumba had died of her disease. I thought about a comment she had made to me about being an example to other women who came to the Luanshya clinic where she worked, offering living proof that knowledge and action can make a difference in the struggle against cervical cancer. Unfortunately, in Zambia, as in other resource-limited nations, anti-cancer efforts still have many difficulties to overcome.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.