THE WAYS WE DESCRIBE THE EXPERIENCE of living with cancer are as varied as the types and stages of the disease. Some people reject battle references, while others find strength in framing their disease in pugilistic terms—likening treatment to a war and surgical scars to badges courageously earned. Some keep the details of a cancer diagnosis close to the vest, while others proudly display awareness ribbons to rally support.

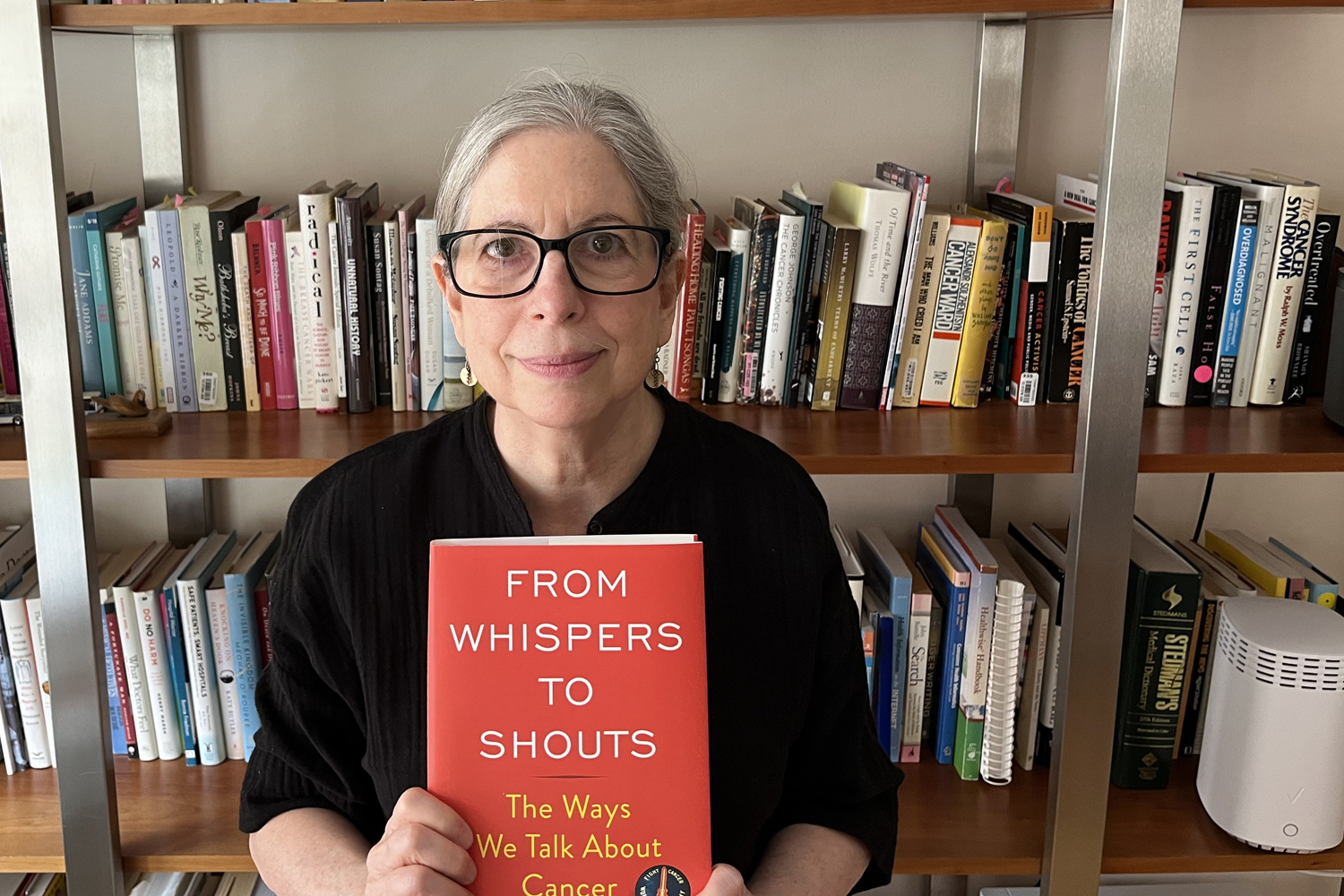

In From Whispers to Shouts: The Ways We Talk About Cancer, former hematologist-oncologist and cancer researcher Elaine Schattner provides an in-depth analysis of how public discussion about cancer has shaped popular perception of the disease over the past century. Tracing historic treatment advances as researchers learned more about the disease, From Whispers to Shouts also focuses on mainstream accounts of cancer in literature, news articles, advertisements, movies and celebrities’ stories.

As more people survive cancer treatment and share their stories, cancer’s public image has been transformed from a death sentence to a roadblock after which many go on to live long lives. However, some cancers can still be portrayed as a hopeless condition, particularly on social media and in news accounts, says Schattner, who was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer in 2002.

Through Sept. 20, we will be discussing From Whispers to Shouts in our online book group.

“I perceived a lot of criticism of the field overall, which makes people distrustful of doctors and hospitals,” she says, noting confusion exists about the value of cancer screening and treatment. “I thought it was a disservice to patients to hear so much negative news when, in fact, there was real progress.”

Schattner, a medical journalist who teaches at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, recently spoke with Cancer Today about how the language we use to discuss cancer has shaped people’s understanding of the disease.

CT: How long did the book take to write?

SCHATTNER: It took me a long time to write this book in part because the topic is a moving target—both the scientific thread of progress and the disclosures of cancer by celebrities. It took me a while to construct the story that I wanted to tell, that I was comfortable with and that I believe to be representative. So that was basically 10 years. Also, I was doing more journalistic work at the time, while teaching at the medical school, so writing the book was a part-time endeavor.

CT: Was it intentional to focus on the role of women as early advocates?

SCHATTNER: I wanted to focus on women as narrators because historically most doctors were men. I think, in general, the voices of volunteers and others who are now what we call activists and advocates were largely overlooked. And they are an important part of what happened in cancer’s emergence into the public sphere.

CT: Why do you think women took on these roles?

SCHATTNER: In the late 1800s, women were rarely employed outside of the home, except in places like factories or as clerks. But some of the women who were wealthy did volunteer work, and they realized that cancer was an area that needed attention. Organizing and raising money for hospitals was an acceptable outlet for women’s work. It was also wealthy women who had time to volunteer. One unfortunate consequence of that is the early awareness campaigns tended to focus on people who were white and affluent, and that doesn’t represent the people who are most affected by cancer. That contributed to some misconceptions about who’s at risk for developing cancer. For a long time, cancer was mistakenly considered a disease that disproportionately affects people of means.

CT: Did women’s efforts disproportionately bring focus to breast cancer compared with other cancers, such as prostate cancer or lung cancer?

SCHATTNER: In writing the book, I realized it took a certain length of survivorship for organizations to form. One thing that was different about breast cancer compared to lung cancer years ago is that very few people survived long after a lung cancer diagnosis. Few people knew they even had lung cancer because open lung surgery was very risky and CAT scans hadn’t yet been invented. Breast cancer was common, and many people survived for years after a breast cancer diagnosis. So those early survivors disproportionately fell into the breast cancer camp. You had a lot of women who were surviving and wanted to give something back to the cause. They wanted other women to know that breast cancer is survivable, and so they formed these organizations.

CT: Let’s talk about the war metaphor for cancer. When did battle language become a part of the vernacular for cancer?

SCHATTNER: First, I prefer to not use battle language. It’s just not my style or how I speak. That said, in writing the book, I learned that the use of battle language goes back at least to World War I, when the war in Europe was likened to a cancer here in the United States. In the 1930s, the Women’s Field Army emerged as a fundraising arm and information-disseminating unit of the American Society for the Control of Cancer, which is now the American Cancer Society. In that group and in the public realm, people used the war metaphor freely, and people seemed to appreciate that. I encountered no criticism of that until the time of Susan Sontag in the late ’70s when she wrote Illness as Metaphor.

I gained some appreciation for the metaphor from my research. In the ’80s especially, there were people who basically decried the use of the term “victim” for cancer patients, which was prevalent then. In that context of the ’80s, when very few people questioned their doctors, the idea of fighting cancer suggested a certain activeness, a lack of passivity about one’s condition. It suggests the idea, which I think is extremely important, that one’s decisions, the information one finds, one’s weighing of options as a cancer patient can make a difference in how you fare. While it’s not my choice of language, I can appreciate where cancer fighters—if you will—are coming from.

CT: What do you hope people will learn from reading your book?

SCHATTNER: The first thing is just how much progress there’s been in cancer research, even just in my lifetime. I would also encourage people to know their sources. There’s a huge amount of information, and there’s also misinformation. Even doctors have different views and conflicts of interest. I also think we’re better now at detection, which is sometimes missed. The earlier we catch cancer, the better. It would be ideal to prevent it from happening at all. Mostly, I hope the book triggers discussion. There are some things people might not agree with, but I hope the book makes people think.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.