BLACK AND HISPANIC PATIENTS are less likely than white patients to receive positron emission tomography (PET) scans upon diagnosis with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to a study published March 2020 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Patients who had PET scans were more likely to survive a year post-diagnosis than those who received only computerized tomography (CT) scans.

Racial disparities in lung cancer rates and outcomes are well-documented. Black Americans are about 32% more likely than white Americans to get lung cancer, and they are the least likely of any racial or ethnic group to survive it.

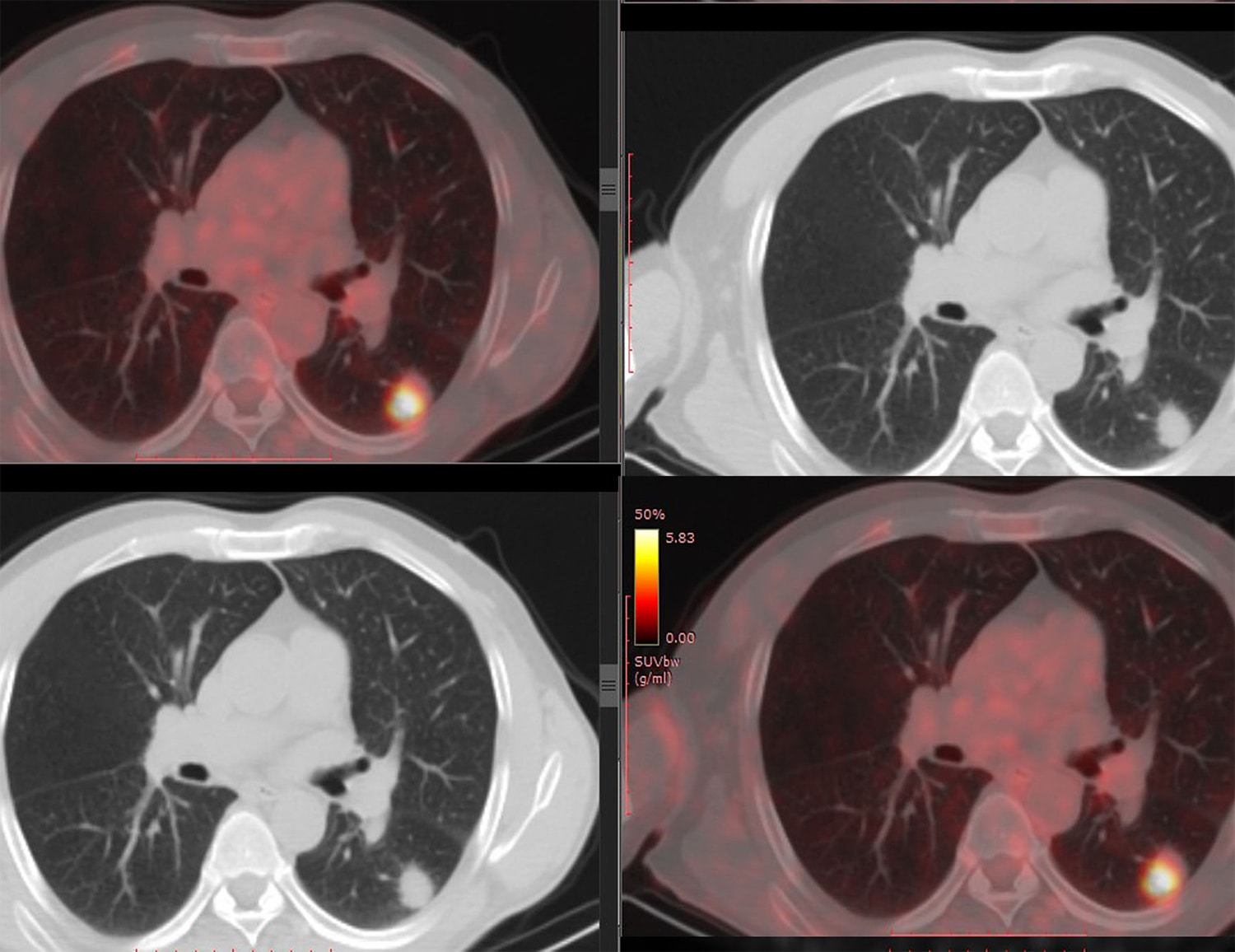

Research has found that in conjunction with CT scans, PET scans can benefit lung cancer patients by improving diagnosis. PET scans, which use a tracer that mimics glucose to label cells with high metabolism, can detect small clusters of cancer cells that CT scans may miss. PET scans often reveal lung cancers to be at more advanced stages than CT scans indicate, and more accurate staging results in patients getting more appropriate treatments. Accordingly, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that patients diagnosed with NSCLC beyond stage 0 receive PET/CT scans, which combine PET and CT scans in one test.

Rustain Morgan, a radiologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, noticed that patients diagnosed with lung cancer didn’t always receive PET scans. Noting the racial disparities in lung cancer survival, Morgan and his colleagues wondered if imaging disparities contribute to outcomes disparities.

To investigate this question, Morgan and his colleagues used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database, which links nationwide tumor registry data with Medicare data on treatments patients received. The study included patients who were diagnosed with NSCLC between 2007 and 2015 at age 66 or older, who were enrolled in Medicare, and who had either a CT scan alone or a PET scan (with or without accompanying CT) at diagnosis. The researchers examined the frequency of CT and PET scans as well as survival in the year following diagnosis.

The study included data from 28,881 non-Hispanic white patients, 3,123 Black patients and 1,907 Hispanic patients. About 78% of white patients, 63% of Black patients and 70% of Hispanic patients received PET scans with or without CT scans. That Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to get a scan that often escalates patients’ staging means that clinicians may underestimate their staging at diagnosis, Morgan says.

Helmneh Sineshaw, a principal scientist at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta who was not involved with the study, says that had the study included patients without insurance, the racial and ethnic disparity might have been larger, since patients from minority groups are more likely to be uninsured, and insurance affects access to diagnostic tests. “Even within a uniform health insurance coverage, such as this Medicare population, these population groups are more likely to have disparate access to recommended care,” Sineshaw says.

The study results bear out previous findings about the benefits of PET scans. Among patients with NSCLC of all types, the chance of surviving a year past diagnosis was more than 20% higher in those who received PET scans than in patients who received CT scans alone.

Morgan says it will take more research to determine the factors behind the racial and ethnic disparities in PET scan utilization. Meanwhile, he says, clinicians should be aware that their own racial and ethnic biases could affect their judgment.

“I think it’s important that we raise that as a possible cause for at least a portion of the difference we see,” Morgan says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.