EFFECTIVE CANCER SCREENING TOOLS are few and far between. That’s why elation greeted the news last summer that heavy smokers who received regular lung CT scans had a significantly lower risk of dying of lung cancer than those who received chest X-rays. Now, the pressing questions are: Who should be screened, and at what age and how often?

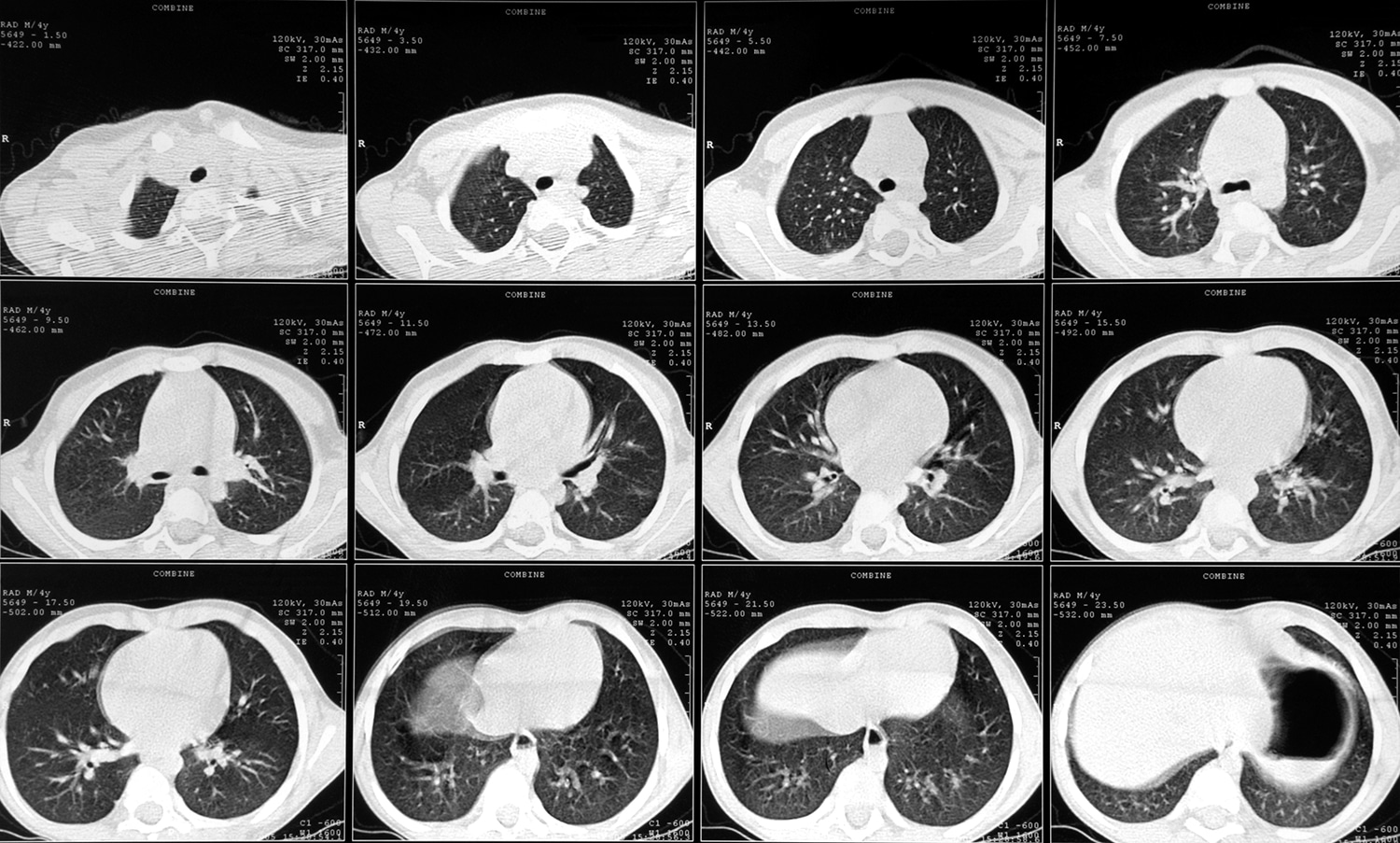

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), which found a remarkable 20 percent reduction in lung cancer deaths, had enrolled about 53,000 current or former heavy smokers 55 to 74 who received a low-dose spiral CT scan or chest X-ray annually for three years. Over five years, 356 individuals died of lung cancer in the group that got CT scans; 443 died of lung cancer among those who received chest X-rays. The findings were officially reported in the Aug. 4, 2011, New England Journal of Medicine.

Because lung cancer is the leading cause of death in the U.S., the number of people who could potentially benefit from CT scanning is “huge,” says Paul A. Bunn Jr., a medical oncologist and the executive director of the Denver-based International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. “The magnitude of this,” he adds, “is colonoscopy and mammography all rolled into one.”

But screening has downsides. The NLST showed that the CT scans have a false-positive rate of roughly 25 percent. This means that about one-quarter of the study participants who received CT scans—6,000 people—underwent additional testing of suspicious lung nodules that were ultimately determined to be noncancerous. As screening guidelines are developed, the benefits of CT screening for heavy smokers will need to be weighed against the emotional and economic cost of false-positive results and follow-up tests, as well as the potential harms of repeated radiation exposure.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology is currently working with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Cancer Society and American College of Chest Physicians to develop guidelines for lung cancer screening. They expect to have them ready in 2012.

In the interim, Bunn and others emphasize that the only patients who should consider CT screening are those with the same risk as or higher risk than the population studied: women and men 55 to 74 who have smoked the equivalent of a pack a day for 30 years. Those who do decide to get screened should be prepared to pay out of pocket because insurance companies may not cover the scans.

Most important, doctors and patients should keep in mind that screening is not better than not smoking, stresses Denise Aberle, a radiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who co-led the NLST. “Anyone who offers CT screening,” she says, “should combine that with risk-reduction strategies for smokers.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.