FOR DECADES, the standard of care for muscle-invasive bladder cancer has been chemotherapy to shrink the tumor followed by surgery to remove the bladder. But a recent clinical trial found adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy may allow certain patients to avoid surgery.

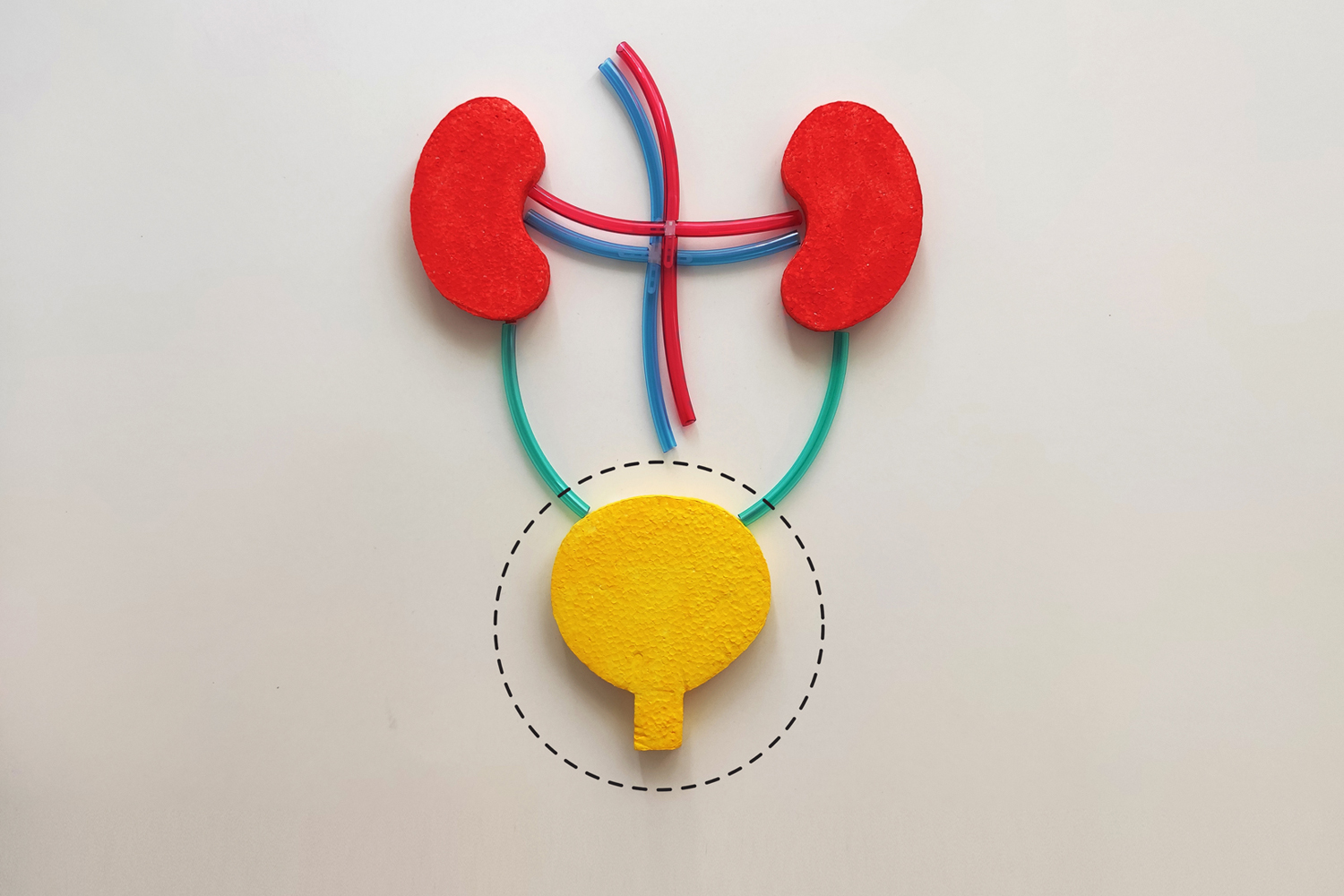

Surgery to remove the bladder, known as a radical cystectomy, involves rerouting the flow of urine out of the body, which may require patients to use an ostomy bag. The complex procedure carries the risk of several side effects, including sexual dysfunction, according to Roger Li, a genitourinary oncologist at Moffit Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida. “In addition to [removing] the bladder, we have to remove pelvic lymph nodes, plus men’s prostates and part or all of women’s internal reproductive systems,” he says. “It’s a complicated, disfiguring procedure that also causes a lot of inconvenience from the urinary perspective.”

With a cystectomy, there’s also an unfortunate paradox: Up to 40% of patients who receive the chemotherapy regimen experience a pathologic complete response, meaning tissue samples from the tumor site show no remaining invasive disease, but surgeons must first remove the bladder to get the tissue samples. “Unfortunately, our tests now just aren’t quite good enough to know without surgery if all the cancer is removed from the bladder,” says Matthew Galsky, a medical oncologist at the Tisch Cancer Institute in New York City.

The study, published November 2023 in Nature Medicine, explored whether some patients could skip surgery after treatment with immunotherapy and chemotherapy. In the phase II clinical trial, 72 people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer received four cycles of Opdivo (nivolumab) and chemotherapy. Patients then underwent tests, including repeated scoping, biopsies and MRIs of the bladder, to determine if they still had any evidence of cancer. Those who had no detectable cancer could choose to forgo bladder removal and receive eight more rounds of immunotherapy. “What we wanted to do with this study was prospectively see if we can better bridge that gap between knowing if there’s cancer left in the bladder or not,” says Galsky, the study’s lead author.

Researchers found that 43% of participants experienced a complete response. Of these 33 people, all but one chose to receive additional immunotherapy instead of having surgery. Two years later, 24 of these patients had no evidence of invasive cancer recurrence.

“This risk-adapted strategy does seem to be an approach that allows certain patients to retain their bladder,” Galsky says. “Perhaps as importantly, most of the patients who did have local recurrence within the bladder could then undergo removal of the bladder without harming their long-term curability as far as we know.”

Li, who was not involved in the study, believes patients will welcome these findings. “Clearly, patients strongly desire bladder-sparing approaches, but we know from previous chemotherapy trials that bladder cancer can arise even after an initial complete response, so we need a reliable way of detecting disease within the bladder itself,” he says.

Galsky is currently running an additional trial that looks at using immunotherapy alone with similar follow-up assessments and then offering additional immunotherapy if participants have a complete response. “Before any new regimen can become standard of care, we need longer follow-up and, ultimately, randomized clinical trials,” he says. “What I know for sure right now is that this study was probably the fastest enrolling study that I’ve been involved with in my career, reflecting patient demand.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.