WHEN WEIGHING DIFFERENT TREATMENTS, oncologists rely on a complex array of factors—including blood test results, pathology reports, imaging scans and genetic tests. Electronic medical records, which aggregate this information, help guide doctors in making treatment decisions. But these tools do little to help guide discussions with patients.

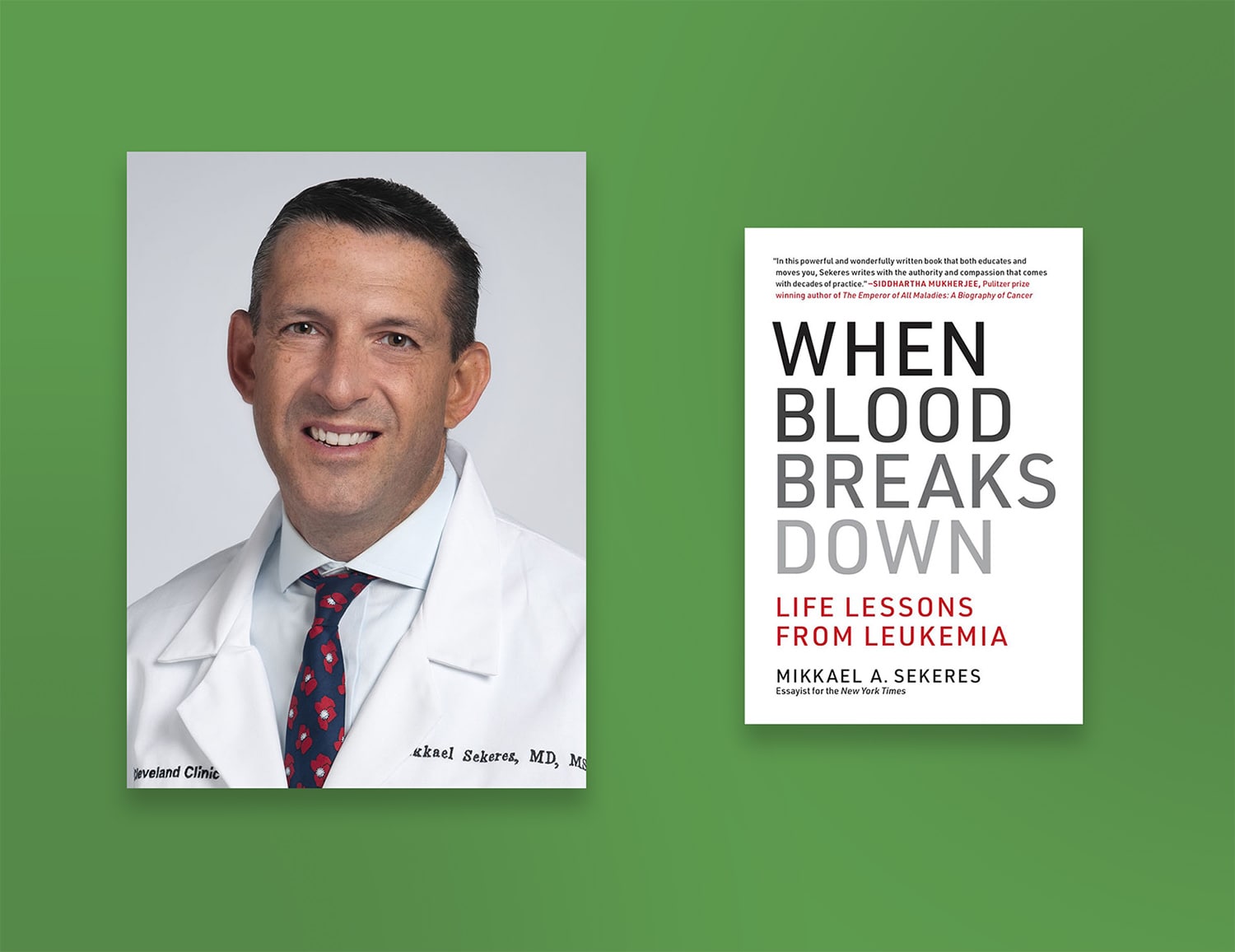

In his newly released book When Blood Breaks Down: Life Lessons from Leukemia, hematologist-oncologist Mikkael A. Sekeres captures the ordinary but somehow universally lyrical encounters between the patient and provider. “My notes [from the electronic medical record] are not things that I would ever want published about patients,” Sekeres says. “They convey the information, they meet the billing codes, but they’re not poetry.” Sekeres, who is director of the leukemia program at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute in Ohio, describes these everyday exchanges by following the treatment journeys of three people, who are amalgamated from his own experiences with real leukemia patients over the years.

He writes about a 68-year-old father and husband diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia who initially opts for low-dose chemotherapy to keep his cancer in check. This approach translates into fewer hospital visits and better quality of life. The treatment course changes, however, when the father’s grown children urge him to take high-dose chemotherapy for a long-shot chance of a cure, which Sekeres estimates is less than 10%.

These up-close views of patients on their worst days but also sometimes at their best are what inspired Sekeres to become an oncologist. In the book, he writes about his first night as a freshly minted medical resident in an intensive care unit. In one room on a noisy floor, a young mother with metastatic ovarian cancer decides she won’t be going on a ventilator. She says goodbye to her children, who are with her in her room. Her husband returns from a nearby pharmacy with a packet of notecards, and the mother diligently starts writing messages in cards for her children to cover every future occasion she will miss.

“These folks are forced to make impossible choices about things that will affect their health and the fabric of their families, and they make these decisions with grace and dignity,” says Sekeres.

Recently, Sekeres spoke with Cancer Today about his desire to spotlight these moments, and how patient stories form the foundation for providing competent care.

CT: What inspired you to write this book?

SEKERES: I think medicine is based on storytelling. A patient tells a doctor or a nurse the story of his or her illness. The doctor or nurse passes that story on to each colleague. I think I was drawn to medicine by these stories, and by the chance to write about remarkable people who we’re honestly privileged to meet.

CT: Your book follows three main characters. Tell me more about these patients.

SEKERES: They’re composites of patients I’ve worked with over the years. No reader could identify a single patient from the details, although people might recognize certain familiar elements. But everything I wrote about in the book—even as fantastic as some details sound—has actually happened to patients.

CT: Do you think it’s more challenging for physicians to build strong relationships with patients today than in the past?

SEKERES: There are certain environments where doctors have time with patients. And there are other environments where they’re seeing a patient every 10 or 15 minutes. In that kind of patient mill, I don’t see how doctors can form the kind of relationships with people that probably first drew them into the practice of medicine.

The other aspect of medicine that drives a wedge in a fulfilling doctor-patient relationship is electronic medical records. That’s important to consider when we think about just how much information is communicated through nonverbal cues. I worry that we lose some of that when we have electronic medical records and people feel under the gun to document, sometimes even during the patient consult, rather than to care.

CT: Are there ways to counteract that?

SEKERES: Yes, but not everyone has the schedule that would allow it to happen. So, for example, I go into a patient’s clinic room, and I do not turn the computer on. I would rather sit, listen to them and chat, and have a meaningful interaction for 15 minutes, and then go back to the workroom and do my documentation. Now what’s suffering from that is probably my documentation. It’s also extra time after the appointment to make these notes, but I’m willing to sacrifice that if I can look somebody in the eye for 10 to 15 minutes.

CT: A poignant part of your book describes difficult conversations about a person’s personal goals in the context of their treatment. What is the role of the physician in these circumstances?

SEKERES: As a physician, my job is to convey information and to help educate the patient enough to make a treatment decision. My other job is to try to assess that patient’s goals and to determine whether the treatment decision aligns with those goals.

When my patient’s goals are not necessarily aligned with his or her family’s goals, that might mean having two conversations, one with my patient alone, and another in front of the entire family. It’s our job as health care providers to be deliberate in identifying that conflict. It might be to say, “I’m hearing this goal from you. I’m hearing this goal from your kids. And I wanted to have a conversation with all of us here about how we can meet everyone’s goals.”

CT: Is that a common dilemma?

SEKERES: More often than not, I have patients who make decisions because of their families’ wishes or challenges. Maybe an older adult is ready to go on hospice, but the kids aren’t ready to lose their parent. Or it may be that a patient has a new diagnosis of cancer, but his wife already has a diagnosis of cancer. He makes a treatment decision that allows him to care for his wife, which may not be in his best interest. That happens all the time, and I think that’s OK. Our decisions are not made in a vacuum. They involve all the fabric of our families.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.