IN 2013, cancer researcher Vicky Forster spotted a familiar face at a scientific conference in Newcastle, England. “I knew he’d be there because I’d looked at the attendee list,” she says. “I thought, ‘This is going to be fun. I wonder if he even remembers me.’”

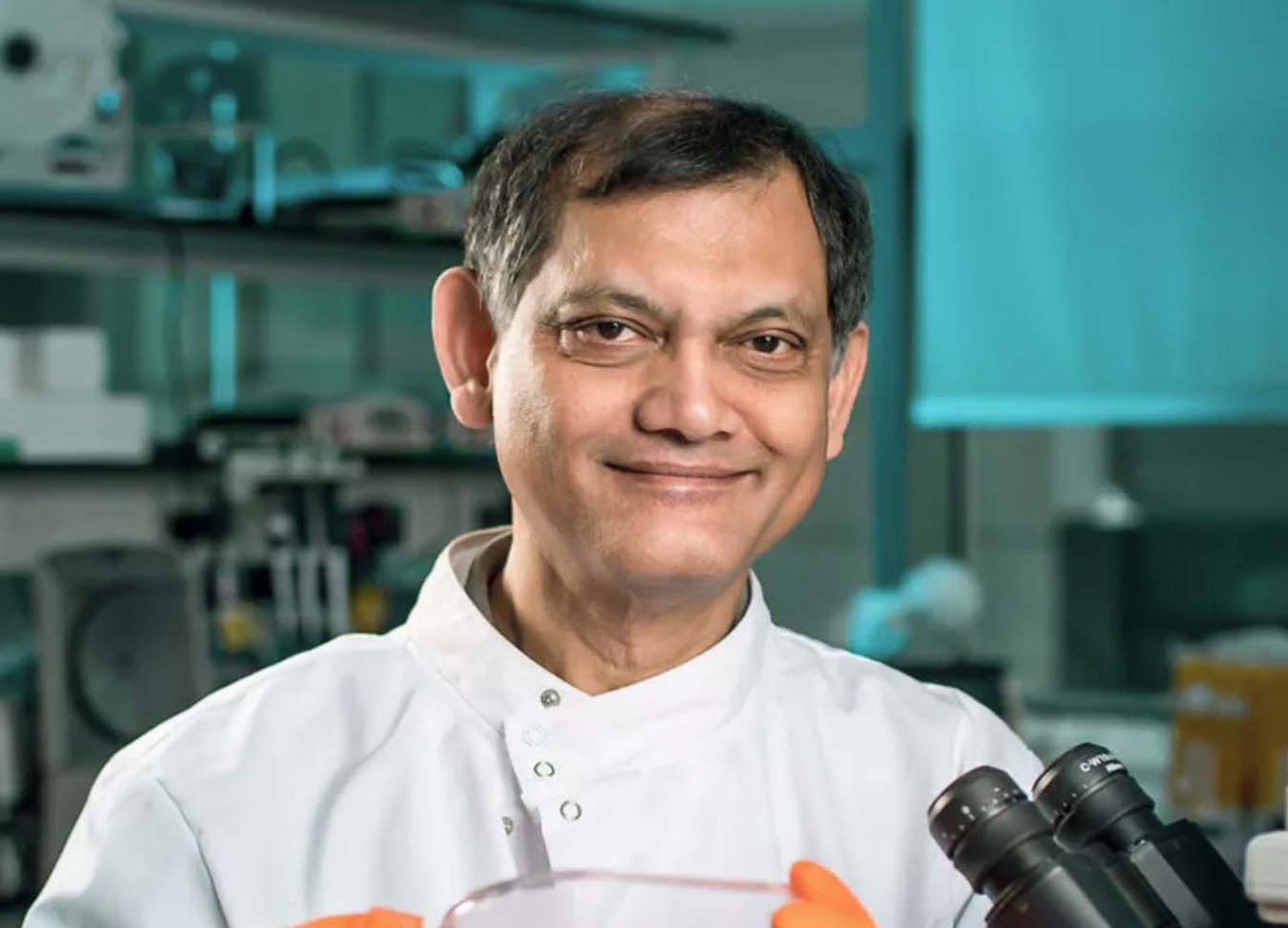

The man she was looking at was Vaskar Saha, a pediatric oncologist who was embarking on a project that would see him split his time between Manchester, England, and Kolkata, India, attempting to increase survival rates for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in both regions.

Both Forster and Saha were attending the conference in a professional capacity as cancer researchers. But they had met long before Forster’s career had even started. She had been diagnosed with ALL when she was a child, and Saha was her favorite doctor. “During the coffee break I found him, and was like, ‘Hi, do you remember me?’’’ says Forster. Saha remembered Forster instantly.

In the Hospital

Almost two decades earlier, in 1994, 7-year-old Forster was out of school with a fever that wouldn’t come down. The family doctor suspected pneumonia. Even the excitement of Christmas Day couldn’t break her routine of naps and general lethargy, so a few days later, her parents took her back to see the doctor in Chelmsford, a city in England where she grew up, about a half hour outside of central London.

“I just wasn’t getting better,” says Forster. A blood test revealed she had ALL, a type of cancer in which the bone marrow produces an overabundance of immature lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. Leukemia is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among children, and ALL accounts for about three-quarters of childhood leukemias. At first, Forster was admitted to the local hospital in Chelmsford, but on New Year’s Day, she was transferred to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in central London.

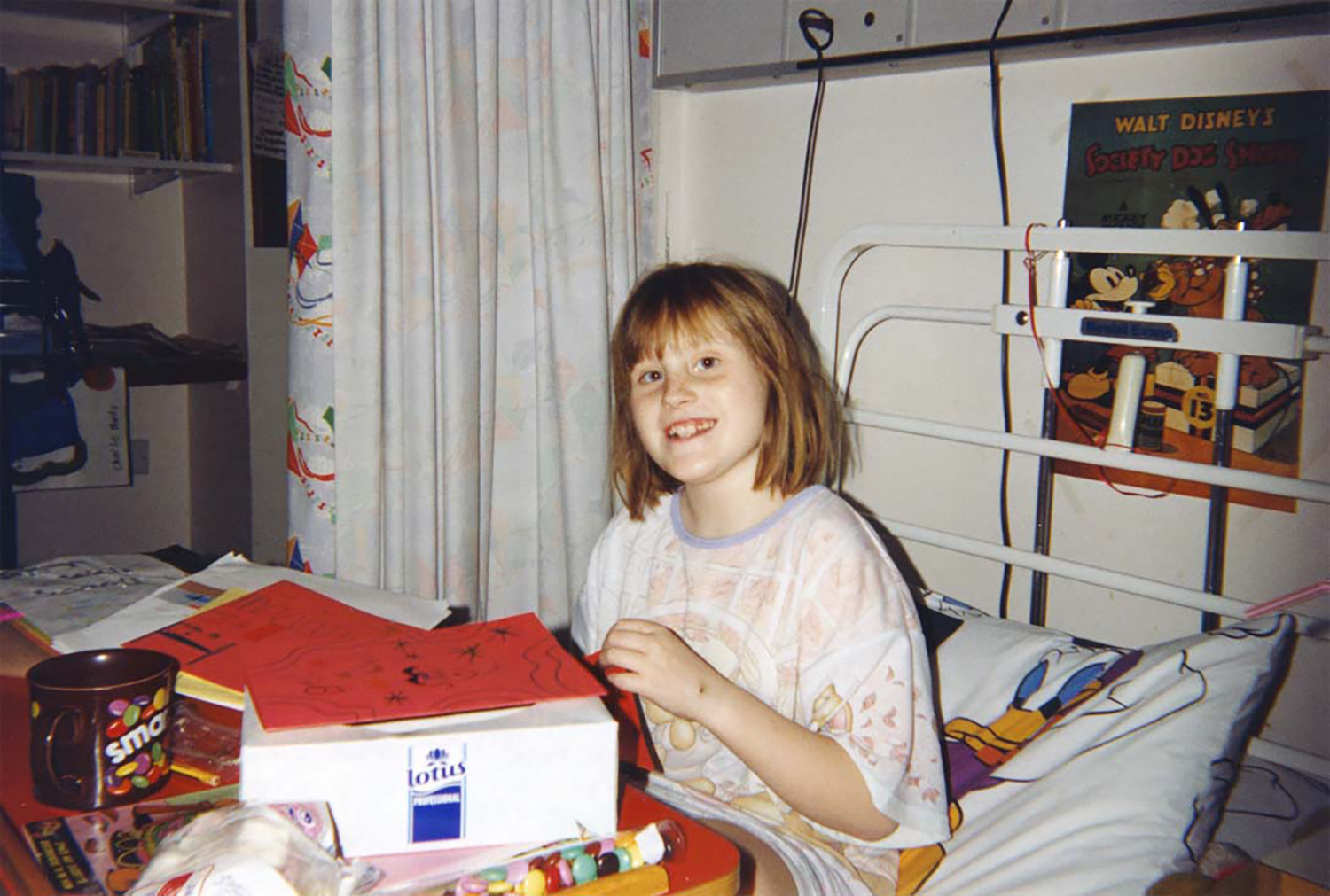

Vicky Forster in her bed at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. Photo courtesy of Vicky Forster

Forster participated in a clinical trial instead of receiving the standard treatment for ALL, which at that time was a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The trial investigated whether cranial radiotherapy, which can cause toxicity as well as other complications, could be omitted in favor of doses of the chemotherapy drug methotrexate injected into the spinal fluid. Both cranial radiotherapy and methotrexate can be used in an attempt to prevent relapses by wiping out the abnormal white blood cells that fill up bone marrow and interfere with normal production of blood cells. Both treatments were known to be effective at reducing the risk of relapse, but oncologists hoped that methotrexate might be just as effective as cranial radiotherapy while causing fewer side effects and lessening their severity.

The trial was a success, confirming that extra doses of methotrexate can replace cranial radiotherapy. However, methotrexate brought its own side effects. A couple of days after Forster’s third injection of the chemotherapy drug and subsequent release from the hospital, she woke up one morning at home completely paralyzed on her left side.

A local doctor was summoned to the house, and upon seeing Forster, immediately called an ambulance to take her back to St. Bartholomew’s. The unfamiliar side effect, now known as stroke-like syndrome, prompted her doctors to fly back from a conference they were attending in Paris.

A day after she experienced the symptoms, Forster’s father took a bathroom break from his post by his daughter’s hospital bed. While he was gone, she was able to move her left arm, indicating a return of motion and feeling to her left side. Forster was excited to share this development with her father, but she also saw a prime opportunity for some mischief. When her father returned from the bathroom, he found his daughter sitting in his seat. Feeling and mobility in her left side came back almost completely within weeks with the help of some physical therapy. Today, the only lasting effects are a loss of the ambidexterity she had as a child and a slight droop in her left eyelid.

Forster credits her recovery to the strong support she enjoyed in the hospital and from her family. “I have some really good memories of my time there, which is always kind of surprising to people,” she says. For example, a pair of teachers helped her keep up with her schooling while in the hospital. That was important because Forster was a clever child with a keen interest in her disease and recovery.

A Thirst for Knowledge

“When I joined the unit, [Forster] was already a patient,” says Saha, now a professor of pediatric oncology at the University of Manchester, then a consultant in pediatric oncology and a senior lecturer at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. “She was a very bubbly girl, [and] she and her mother were always full of questions. She was one of the fortunate ones. She was cured and she went off.”

Forster was in and out of the hospital over a period of months and developed bonds with members of the staff, but to this day she describes Saha as being her favorite doctor because he was willing to go above and beyond to satisfy her curiosity.

Pediatric oncologist Vaskar Saha treated Vicky Forster for acute lymphoblastic leukemia when she was a child. Photo courtesy of the University of Manchester

Forster acknowledges that even today, she doesn’t do well handling things she doesn’t understand, and this was very much the case when she was a child on a cancer ward. She remembers her laundry list of questions: Why am I taking this medicine? Why are the platelets orange? Why does that drug make my pee red? “I would ask all these incessant questions,” she says. “He’d take the time to answer them, even if it meant coming back at the end of the day when he was about to go home and just sitting on the end of my bed and talking to me about what was going on.”

“She’d be full of questions—why do you get leukemia, how does it work, stuff like that,” says Saha. “It’s great fun to engage with someone like that because I was a young consultant in those days, and you’re learning how to explain science simply, right? If you can explain it to a child, and the child understands, you think, ‘Maybe I’m getting it right.’”

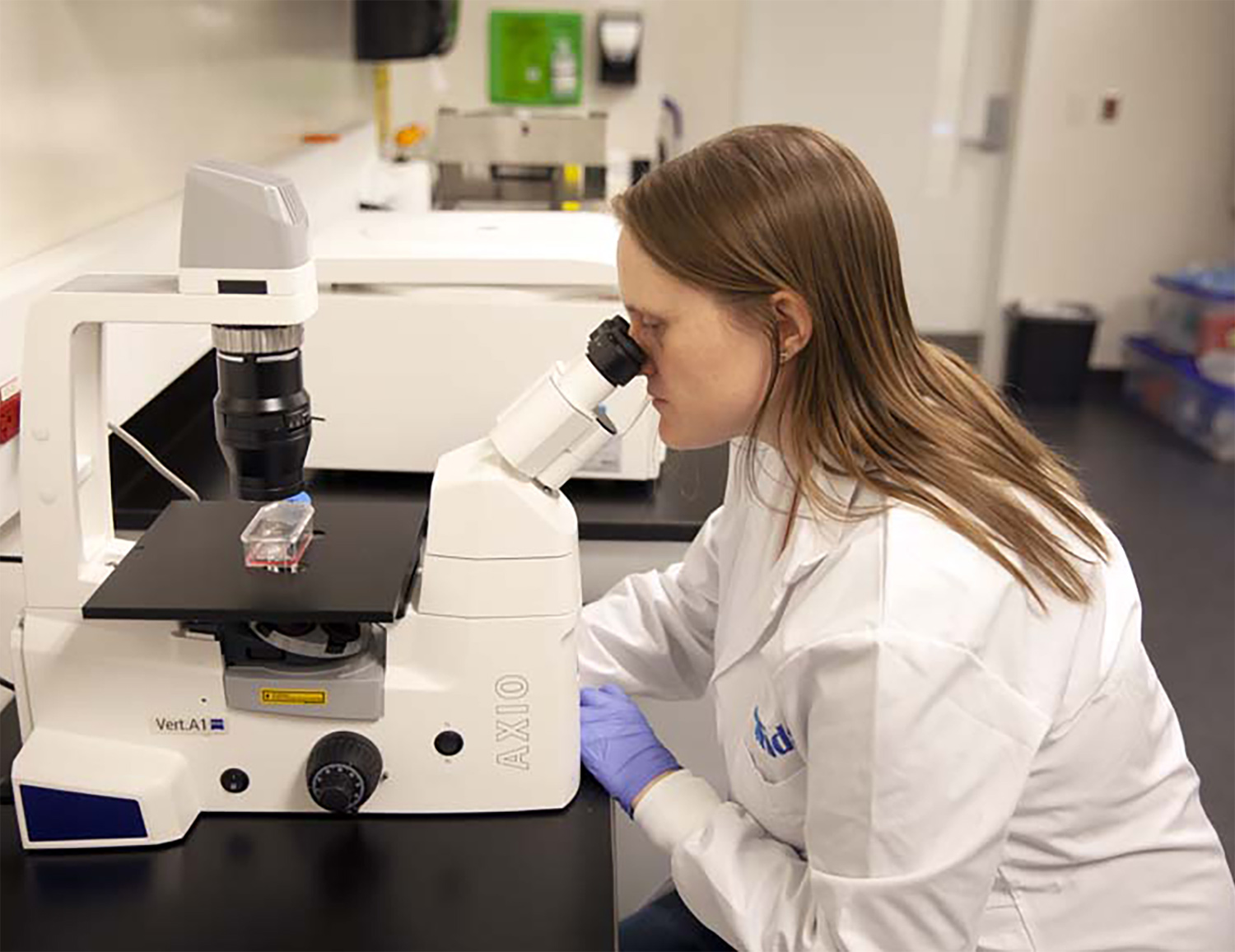

Vicky Forster in a lab while studying for her doctorate at Newcastle University in England. Photo courtesy of Vicky Forster

Forster had been interested in science from an early age, tinkering with electronics projects with her father and dreaming about becoming an astronaut. Her hospital experiences changed her course. Conversations with Saha and others flipped her interest from physics to medicine, propelling her toward receiving an undergraduate degree in biomedical sciences from Durham University in 2008. She would go on to earn a doctoral degree in cancer research at Newcastle University. Currently she’s a postdoctoral research fellow at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“I had nothing to do with that,” says Saha of Forster’s entry into medical research. “You do feel proud. I’m like an uncle, and I’ve got a brilliant niece. But I think she was a genuinely bright girl, and she would have gone into science anyway.”

Vicky Forster is a science communicator as well as a scientist.

Vicky Forster’s experiences as a scientist and a patient have led her to wear many hats. In addition to her pediatric cancer research, she also writes about science and health for general audiences, drawing on her firsthand knowledge of what it’s like to be a patient eager for more information. And in 2019, she co-founded Cancer Survivor Social Media, an organization that runs regular online events designed to foster communication and collaboration among medical professionals, researchers, patients and survivors.

“What if every patient and every survivor had an experience like I did, which could influence research or policy for the better?” Forster asks. “I can guarantee that pretty much every single person will have [such experiences]. It’s just, we don’t effectively make spaces for them to communicate their experiences in a way that researchers can use or understand.”

Forster acknowledges that patients are included more regularly now in deliberations about research, for example, in grant selection and clinical trial design, but she says there is still a long way to go. Some researchers work well with patient advocates, she adds, but others seem to treat it as a requirement rather than an opportunity. “In some cases, unfortunately, you can end up with a very one-sided, very unfulfilling relationship for the patient advocate,” she says.

Communication is one area where there is room for improvement, says Forster. Her ability to understand medical jargon is far above the norm, so she encourages researchers to find a common language with patient contributors who might feel locked out of a project that’s only described using highly technical terminology.

“There’s a great voicing of different opinions. It’s very respectful,” says Maryam Lustberg, a breast oncologist and the chief of breast medical oncology at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut, who has taken part in and moderated several Cancer Survivor Social Media Twitter chats (#CSSMchat). “[The survivors] aren’t waiting for us ‘experts’ to tell them what to think, they’re freely sharing their ideas.”

Putting the focus on a community of diverse voices with varied experiences suits Forster better than serving as a figurehead. “Being a cancer survivor is part of my identity,” she says. “I’m comfortable with it, and I want to use it for good. But I don’t need to sign a book deal or become wildly famous. I’d rather use my experiences to pull other people up and make sure they have a platform.”

The Back of Your Mind

After Forster’s cancer had been in remission for two years, she was told her treatment was completed. Her experience had steered her toward a career in medical research, but she was able to move on with her life in most respects.

One thing continued to occupy her mind, however, as her career in research began to take shape. What was the cause of her strange response to methotrexate—the stroke-like syndrome? “My mum occasionally would quiz me about it,” says Forster. “Has anyone figured out why that happens yet? Does it happen to other kids?”

In 2014, Forster was giving a talk in Newcastle about her treatment, her research into leukemia, and the side effects of methotrexate she experienced as a child. After the talk, a man approached her. “He said, ‘My daughter Jenna was diagnosed at the same age you were. She had that side effect from that horrible methotrexate. She couldn’t move from the neck down,’” Forster recalls. Forster asked when Jenna was treated and was surprised to hear it had been only a few years prior to their conversation.

Vicky Forster peers into a microscope at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Photos of Forster appearing in this issue were shot before the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by David Cha

“I guess I assumed people would have figured it out by now,” she says of the side effect. This chance encounter convinced Forster to look into the problem. She reviewed the medical literature and found that plenty of people had described similar experiences to hers and Jenna’s, but there hadn’t been much work put into explaining why it happened. Most patients had recovered from the paralysis, but some hadn’t. Forster was eager to push further, but she realized she would need help.

“I was very aware of the fact that I wasn’t a neuroscientist, and neuroscience would really be needed to solve this problem,” says Forster. She began moonlighting by performing experiments using neural cell lines she borrowed from scientists she knew and a laboratory supply of methotrexate. The neural cells were more acutely sensitive to methotrexate than any of the other cell lines she was able to compare them with, and things began to snowball from there.

Forster worked with collaborators from Newcastle University to grow healthy neural cells from stem cells. (The ones she had been using previously came from brain tumors). The results suggested that methotrexate might be particularly toxic to the brain’s glial cells, which she describes as insulation that protects neurons—the cells that transmit information throughout the nervous system. “I hypothesized with my very preliminary results that the methotrexate was causing holes in this insulation of the nerve,” she says. “Because [glial cells] are particularly sensitive to it, the neurons are mostly OK, but these glial cells seem to freak out and stop doing their jobs when you treat them with methotrexate.”

In December 2018, neuro-oncologist Michelle Monje and her colleagues at Stanford University in California published a paper in Cell that corroborated the hypotheses Forster arrived at in her own research.

“It’s figured out, better than I ever could do with a year of funding at Newcastle. It’s really figured out the crux of the problem,” says Forster of Monje’s research. “She and I have had several conversations about it. It’s fantastic because her lab is pursuing ways of preventing these side effects, which could someday benefit people like me who have acute effects from methotrexate, as well as people treated with the same drug for breast cancer who have long-term cognitive effects.

“Michelle and I never talked until we’d both done our separate things, but for me as a junior scientist, to have my hypothesis validated by someone like her is pretty cool,” she adds.

Vicky Forster at a park near her home in Toronto, where she currently lives and works. Photo courtesy of Vicky Forster

The pride Saha takes in Forster’s accomplishments is evident when he looks back on a call he received from a colleague who had been an examiner for her doctorate at Newcastle University informing him that she had passed with flying colors. “You just feel happy and proud when you hear that news,” he recalls. “What keeps us going is the stories like Vicky.”

But as a pediatric oncologist, Saha is wary of lingering on his successes. “In Vicky’s case, the way I look at it, I did my job, which was to help her through it,” says Saha. “For the kids that didn’t make it, I didn’t do my job. I failed.

“I think most of us remember our failures more vividly than our successes,” he adds. “When you win a game or a match, for a few days you remember it and you’re euphoric. But all your life, you remember the games you lost.”

Forster never wanted to be defined by cancer, though she has been able to harness her experience to inform her work. Her firsthand experience exposed her to problems she could set her mind to resolving, but her accomplishments are the result of her hard work, not her diagnosis.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.