People with a rare hereditary condition that can cause hundreds to thousands of precancerous polyps to form in the digestive tract over time have a very high likelihood of developing colorectal cancer. Findings from a new study suggest it may be possible to reduce the number of colorectal polyps that develop by using targeted therapies that block specific proteins involved in their growth.

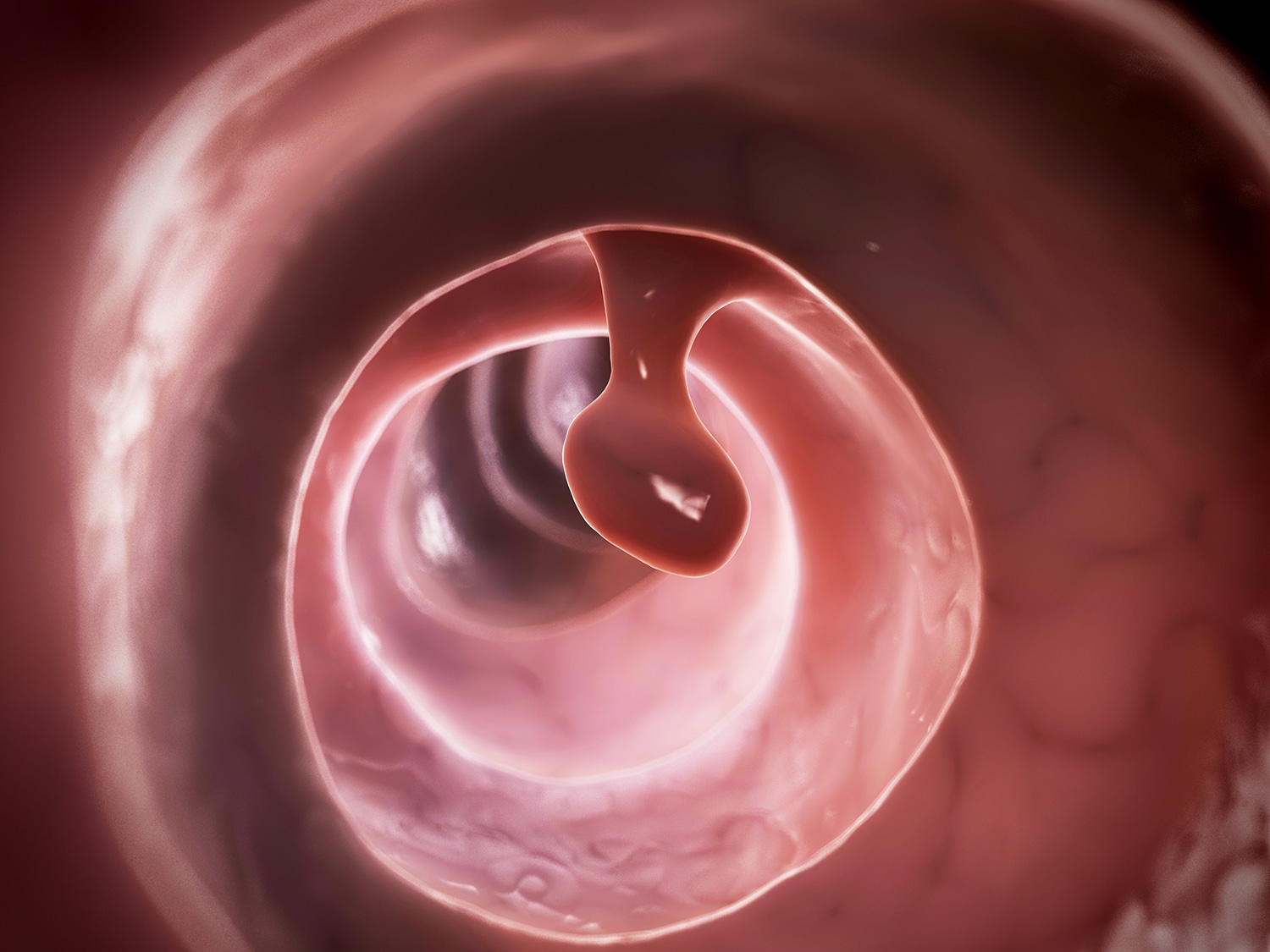

Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) are born with mutations in the APC gene, which controls cell growth. The mutations affect two proteins that spur polyp growth, cyclooxygenase (COX) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines for individuals who inherit FAP recommend endoscopic screening starting at 10 to 11 years old. Once polyps are found—which occurs in people with FAP in their teens—annual colonoscopies are performed to identify and remove the precancerous polyps. When the polyps can no longer be controlled, the guidelines recommend a colectomy, surgery to remove all or part of the colon.

More than half of all FAP patients will also develop polyps in the duodenum, the starting point of the small intestine, putting them at risk for duodenal cancer. N. Jewel Samadder, a gastroenterologist and director of the High-risk Cancer Clinic at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, launched a randomized trial in 2010 to study the effects of a two-drug combination that targets two proteins contributing to polyp growth: the anti-inflammatory drug Clinoril (sulindac), a COX inhibitor, and the targeted therapy Tarceva (erlotinib), which blocks EGFR. The combination was compared to a placebo. The initial findings published in 2016 in JAMA showed that after six months, the treatment group had a median decrease of 2.8 duodenal polyps. Those who received the placebo had a median increase of 4.3 duodenal polyps.

Samadder and his team recently re-analyzed the data to see what effect the two-drug combination had on colorectal polyp growth in 82 people with FAP, including 22 who still had their full colon. The findings from this study, published in the May 2018 JAMA Oncology, showed the drug combination also reduced the number of colorectal polyps. “We were able to precision target the mechanism for why these patients were getting polyps,” Samadder says.

For more than two decades, Clinoril has been used alone to control the number of polyps in people with FAP who have retained part of their rectum after colectomy. But it doesn’t prevent the need for a colectomy, says Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez, a medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Right now, he says, “the goal is to identify new drugs or combinations of drugs that” work better than Clinoril.

Samadder says more research is needed to determine the best dose of Clinoril and Tarceva to use together and how long patients should stay on the treatment.

Side effects of the drug combination can include skin rash, mouth sores and diarrhea or nausea. Tarceva is approved to treat some types of lung and pancreatic cancer. However, it is not an approved treatment for colon cancer or for chemoprevention for any cancer. Insurers are not likely to cover its use to prevent polyps in people with FAP until more research has been conducted.

Samadder recently launched a phase II clinical trial to study whether a lower dose of Tarceva alone reduces duodenal and colorectal polyps in people with FAP. “Can we use a medication to prevent cancer?” asks Samadder. “This is the future of precision cancer medicine. Hopefully, it will come to fruition.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.