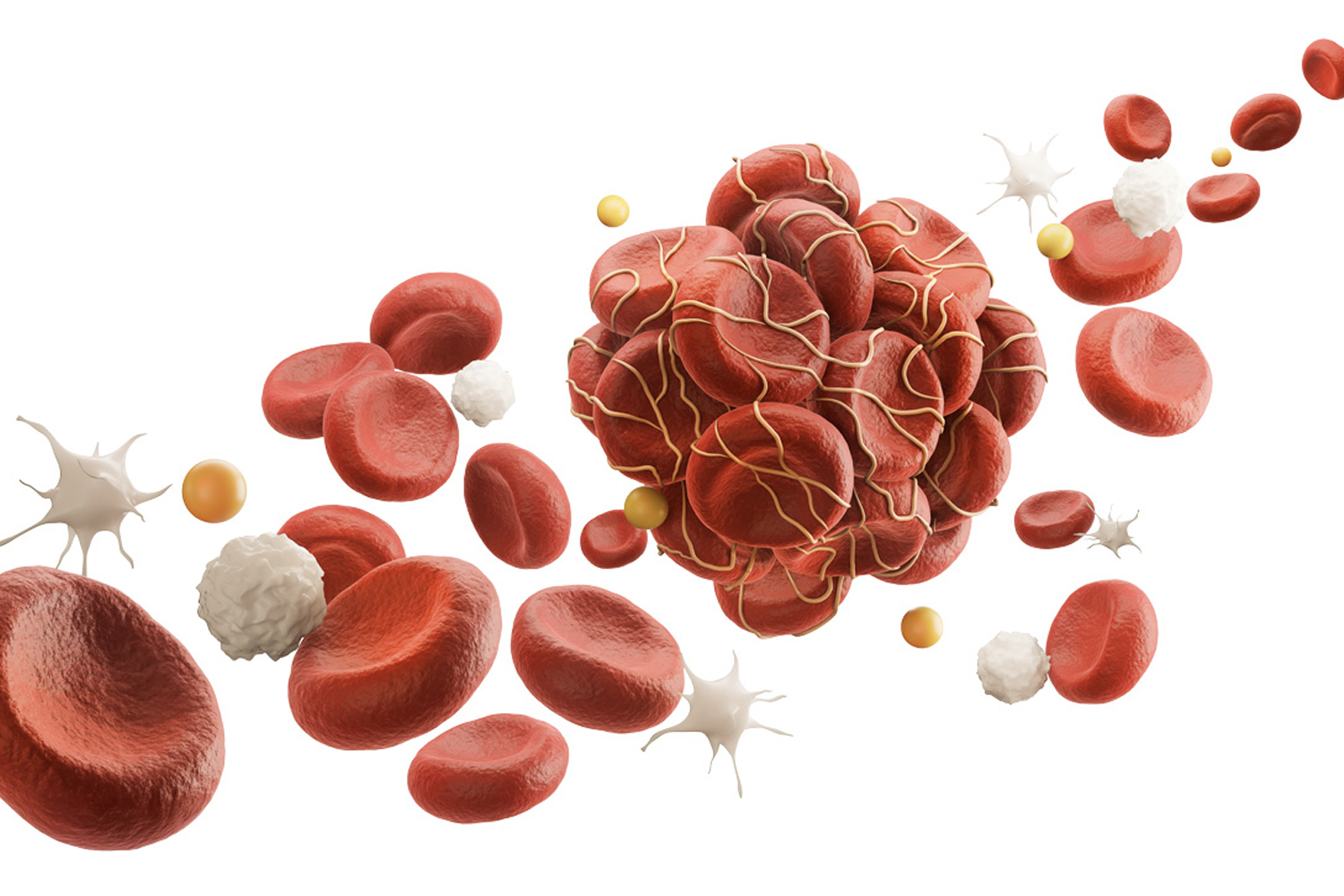

UP TO 20% OF PEOPLE with cancer will face a second life-threatening health problem: blood clots. Clots are clumps of blood that help stop bleeding after injury, but when they form internally, they can prevent blood from traveling through veins or arteries. Some dangerous blood clots, formally known as venous thromboembolism (VTE), occur in veins far beneath the skin, most often in the legs. These clots can also travel to the lungs and block oxygen delivery, which can be fatal.

Blood clots are a leading cause of death in cancer patients, second only to cancer itself. A 2021 study found 3% of people with cancer have a blood clot during the year after diagnosis, which makes the clotting risk for cancer patients nine times that of the general population. Both cancer and its treatment contribute to this elevated risk. Cancers themselves release a substance that promotes clotting, while some cancer treatments, including chemotherapy and targeted therapies, can damage blood vessels and cause inflammation that increases clotting risk.

To prevent blood clots, doctors may recommend anticoagulants, or blood thinners, to cancer patients who have a history of blood clots, are hospitalized, are having major surgery, or are starting chemotherapies known to increase clotting risk.

If a person with cancer develops a blood clot, their doctor generally will prescribe a blood thinner. Examples of blood thinners include heparin, which is injected, and Eliquis (apixaban), which comes as a pill. For Eliquis, doctors will prescribe a 5-milligram tablet twice daily for the first six months. After that, patients will often continue taking a blood thinner for as long as they are in treatment or have cancer, which could be a long time.

Yet doctors are cautious when prescribing blood thinners because people with cancer already have a higher risk of bleeding than the general population, explains Alok Khorana, a hematologist-oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute who studies blood clotting in cancer patients. Tumors can invade blood vessels, which can cause internal bleeding, and can also bleed as they grow. Chemotherapy can reduce a person’s levels of platelets, cell fragments in the blood that promote clotting. Having low platelet counts results in impaired clotting and a higher risk of bleeding. “The risk is obviously magnified when you go on a blood thinner,” Khorana says.

With this risk in mind, researchers recently explored whether a lower dose of Eliquis could be as effective in preventing future clots. “The question was: At six months, should we continue the full dose? Or is it possible to consider dose-lowering with a perspective that patients could have fewer bleeding complications?” says Isabelle Mahé, a cardiovascular disease specialist at Louis-Maurier Hospital in Colombes, France.

To explore this question, Mahé led a phase III clinical trial called the Apixaban Cancer Associated Thrombosis (API-CAT) trial. In it, 1,766 people with active cancer who had experienced VTE and had taken a blood thinner for at least six months were randomly assigned to take either a full dose (5 milligrams) or a reduced dose (2.5 milligrams) of Eliquis twice daily for one year. Researchers monitored participants for subsequent VTE and any bleeding incident that required medical attention.

The study, published April 10, 2025, in the New England Journal of Medicine, found 15.6% of people in the full-dose group and 12.1% of participants in the reduced-dose group experienced clinically relevant bleeding. “Bleeding complications are very difficult for [patients] in clinical practice. They have to stop their treatment. They have to go to the hospital,” Mahé says. “This reduction in bleeding complication[s] is very relevant for patients, but also for clinicians who have to manage those patients.”

Among people receiving the full dose, 2.8% experienced another blood clot, compared with 2.1% of those in the reduced-dose group. People in both groups, regardless of their cancer type, had a similar risk of dying from a blood clot, Mahé notes.

“[You’re] not losing anything by dropping to half a dose, in terms of protection from a second blood clot,” says Khorana, who was not involved in the trial. “In my practice, once people hit six months, I switch to half the dose. It’s definitely practice changing.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.