CHEMOTHERAPY, RADIATION THERAPY AND CERTAIN CANCERS can reduce the number of white blood cells called neutrophils present in the body, resulting in a condition known as neutropenia. A neutropenic, or low-bacterial, diet is a method of counteracting the heightened risk of infection associated with neutropenia.

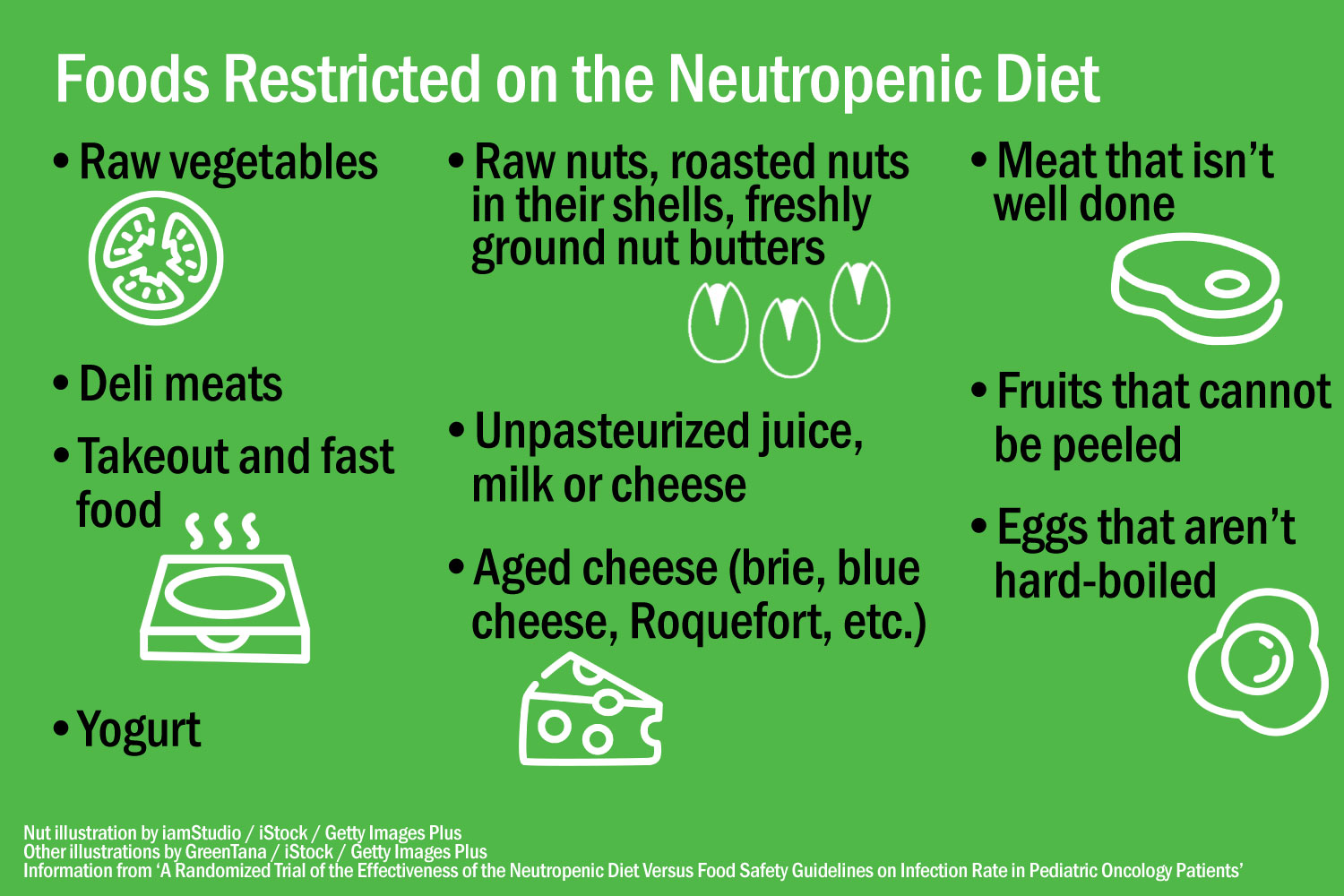

There’s no one standardized definition of a neutropenic diet, but patients are typically instructed to adhere to basic food-handling rules, like ensuring that meat and eggs are cooked thoroughly. However, there are additional restrictions; most commonly, uncooked vegetables and most uncooked fruits are not allowed (although canned items and pasteurized juices are permitted). Patients may also be told to avoid other things, like certain cheeses, spices added to food after cooking, raw nuts, yogurt or deli meats. These limitations are intended to prevent the introduction of potentially harmful bacteria to the gut.

However, there has never been strong scientific evidence that neutropenic diets benefit patients. A randomized trial published in the January 2018 issue of Pediatric Blood and Cancer showed that following a neutropenic diet did not protect pediatric patients from infection any more than simply following the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) food safety guidelines. An abstract presented at the 2018 American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting describes results of a review of five studies encompassing 1,068 patients that examined the effects of following a neutropenic diet. The review found no difference in the rate of major infections between patients who adopted a neutropenic diet and those who maintained a normal diet.

Despite findings calling the neutropenic diet into question, some institutions still appear to promote it. Another ASCO abstract looks at recommendations related to the neutropenic diet published on websites belonging to the top 20 institutions featured on the U.S. News Best Hospitals for Cancer list for 2017. Seven institutions recommended the diet, while four recommended against it.

A final abstract describes efforts at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas, between September 2016 and September 2017 to phase out use of the neutropenic diet by educating physicians and removing the ability to prescribe the diet to patients from the institution’s electronic medical record.

Arjun Gupta, an internist and chief resident at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, was the lead author of the third abstract and a contributing author on the second. He also co-authored a paper on the neutropenic diet published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine on May 30 for their “Things We Do for No Reason” series—a set of reviews of hospital practices that may not be evidence-based.

A paper published in the January 2018 issue of Pediatric Blood and Cancer described the neutropenic diet using the criteria above, but definitions vary between institutions.

Gupta was inspired to challenge the use of the neutropenic diet while on rotation in a cancer ward, after his supervisor instructed him to look out for ingrained practices that didn’t make sense from an outside perspective.

The instruction resonated with him. “I grew up in India, and that’s where I attended medical school,” Gupta says. “It’s obviously a very different perspective, coming from a resource-limited setting to the U.S., which is perhaps more extravagant in everything that we do. So, I was always on the lookout for things we do for no reason, or things that we do without any proven benefit but coming at a cost to both the society and the patient.”

Gupta observes that while there’s no evidence that the neutropenic diet can reduce the risk of infection, patients on the diet reported a negative effect on their quality of life. He gives the example of a patient who wanted to eat a pear but was prevented from doing so. This may seem like a minor limitation, but dietary strictures can have a dramatic effect on cancer patients, who may already be limited in what they can eat by chemotherapy side effects like nausea, reduced appetite and mucositis, a painful inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract that makes it difficult to swallow. Outside of a hospital environment, individuals are expected to adhere to the diet for themselves, which can cause further distress if they’re unable to do so.

There’s also a lack of standardization. Gupta spoke to hospital kitchen staff and found that many had only a vague understanding of what a neutropenic diet consisted of. Staff might refer to the importance of food being “cooked well,” but there was little specificity as to what that meant. Furthermore, he found that different medical institutions were prescribing the diet inconsistently; one might begin the regimen at a particular stage of the patient’s chemotherapy treatment, while another might refer to the patient’s neutrophil count.

“I think it’s sort of strange how diet, exercise, all of these things aren’t regarded as prescriptions, while we’re so meticulous about the medications that we give to our patients,” Gupta says.

Despite his desire for more institutions to follow in the footsteps of Parkland Health and Hospital System in dropping the neutropenic diet, Gupta maintains that patient safety remains paramount. He suggests that anyone preparing food for a person with neutropenia follow the FDA’s safe food handling guidelines, which include instructions on maintaining a clean environment, keeping raw meat from contaminating other foods, refrigeration and heating certain foods to a safe temperature. All hospital food should meet these criteria already, and most individuals cooking outside the hospital setting will follow similar standards.

“The last thing that I want in all of this hullabaloo about the neutropenic diet is that a patient gets sick because of us removing it,” said Gupta. “The message is not, eat whatever you want. It’s that the focus should be on preparation and cleaning.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.