Could an Anatomical Discovery Reduce Treatment Side Effects?

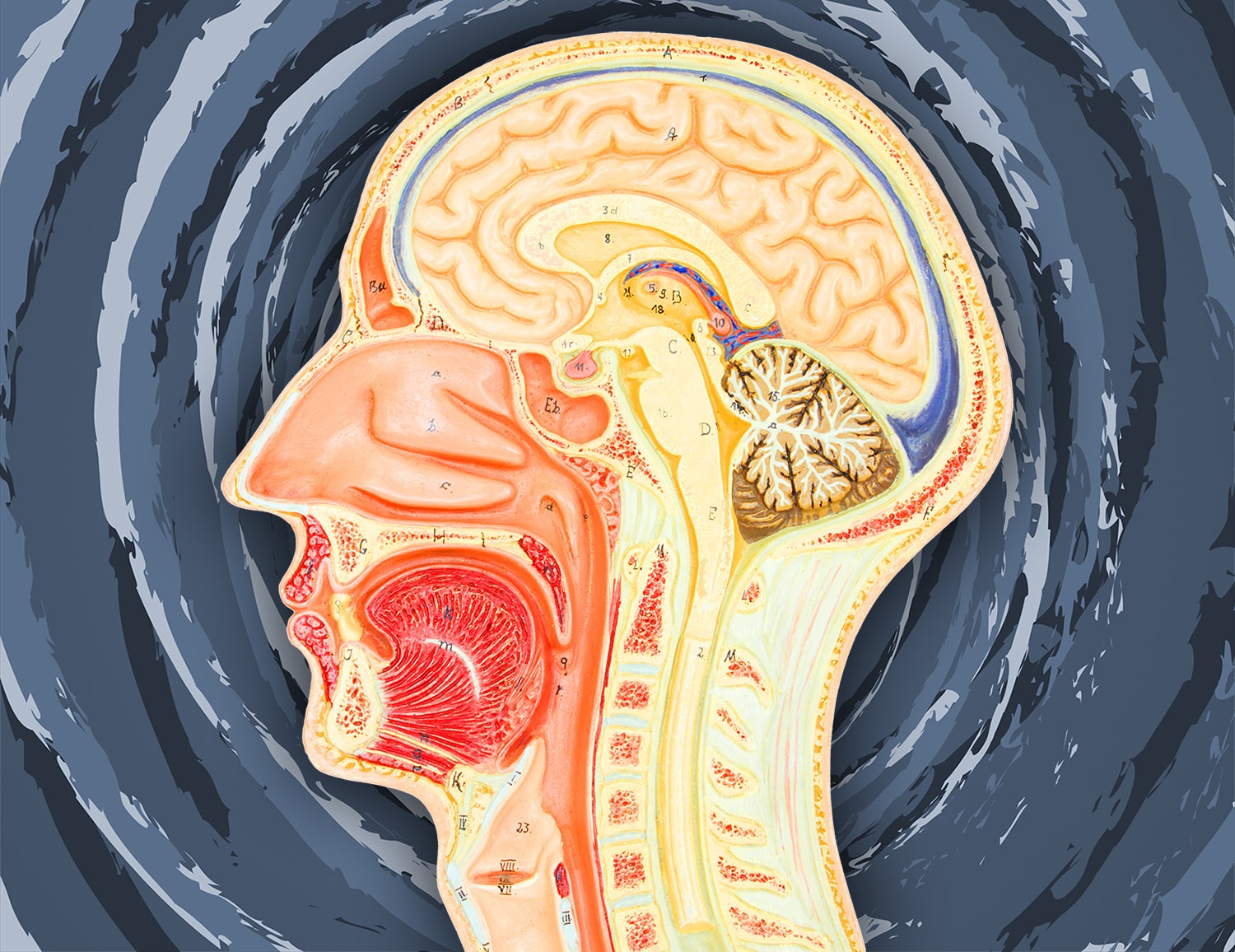

A paper published Sept. 23 in Radiotherapy and Oncology describes a previously undiscovered set of salivary glands, the New York Times reports. The researchers describe a pair of salivary glands located in the nasopharynx, or the upper section of the throat behind the nose. They first noticed these glands while performing a new form of PET/CT scan that can identify tissue expressing PSMA, a protein often expressed by prostate cancer cells and also by salivary glands. The doctors found that the supposed extra glands lit up on scans from 100 people with prostate or urethral cancer who received scans to determine if their cancers had grown or spread. They also identified the glands in two people who had donated their bodies for cadaver studies, dissecting them and characterizing the tissue. Radiation oncologist Wouter Vogel of the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, who co-authored the study, told the New York Times that the presence of these glands could help explain the dry mouth and swallowing problems that are common for people undergoing radiation for head and neck cancers. Radiation oncologists take measures to avoid irradiating other salivary glands, but since these glands were unknown, oncologists haven’t been trying to protect them. Looking back at the clinical histories of 723 patients with head and neck cancer, the researchers found that higher doses of radiation to the area containing the glands were associated with dry mouth and swallowing troubles. Other researchers commenting on the findings said that more data was needed to understand the findings.

Age Matters for Treatment Response

A trial testing Avastin (bevacizumab) for treatment of melanoma patients with a high recurrence risk did not meet its primary endpoint of improving overall survival, although it did increase the interval in which patients were free of disease. An analysis after the fact found age influenced response to the treatment, according to a paper published Oct. 23 in Clinical Cancer Research. Avastin targets VEGF, a protein that promotes the formation of blood vessels. Blocking the growth of blood vessels is thought to help prevent metastasis. The researchers found that people younger than 45 who received Avastin had improved disease-free survival, while older patients did not. Looking at data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, the researchers found that VEGF expression and expression of its receptors was decreased in tumor samples from older patients, even though older patients have increased blood vessel formation. Research in aged mice indicated that targeting VEGF is not sufficient to prevent the growth of blood vessels. Instead, targeting a second protein, sFRP2, reduces blood vessel growth in aged mice. If sFRP2 is artificially increased in younger mice, targeting VEGF is no longer sufficient for reducing blood vessel growth. “Our work highlights the fact that younger patients can have very different responses to a given therapy compared with older patients. Understanding that the age of a patient can affect response to treatment is critical to providing the best care for all patients,” study co-author Ashani Weeraratna of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore said in a press release.

Privately Insured Patients Have Better Access to High-Volume Hospitals

People who receive surgery for their cancer at hospitals that perform a high volume of surgeries tend to have better outcomes than those receiving surgery at low-volume hospitals. A study published Oct. 21 in Cancer finds that people with various cancers who have Medicare, Medicaid or no insurance are less likely to have access to high-volume hospitals. The researchers looked at records in the National Cancer Data Base for more than 1.2 million Americans who had breast, prostate, lung or colorectal cancer between 2004 and 2016. For those with breast, prostate or lung cancer who lacked private insurance, the odds of getting surgical care at a high-volume center were reduced across the study period. People with colorectal cancer with Medicaid or without insurance had a reduced chance of getting care at a high-volume center in the early years of the study, but by the final years of the study access to high-volume centers had improved for these patients.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.