On March 8, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the immune checkpoint inhibitor Tecentriq (atezolizumab) in combination with the chemotherapy drug Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) for a small group of patients with advanced breast cancer. The approval is for patients with triple-negative disease whose tumors are infiltrated by immune cells that express the protein PD-L1.

“These are the first positive results of an immunotherapy in any type of breast cancer,” says Leisha A. Emens, a medical oncologist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Cancer Center and a lead investigator in the clinical trial that led to the new approval.

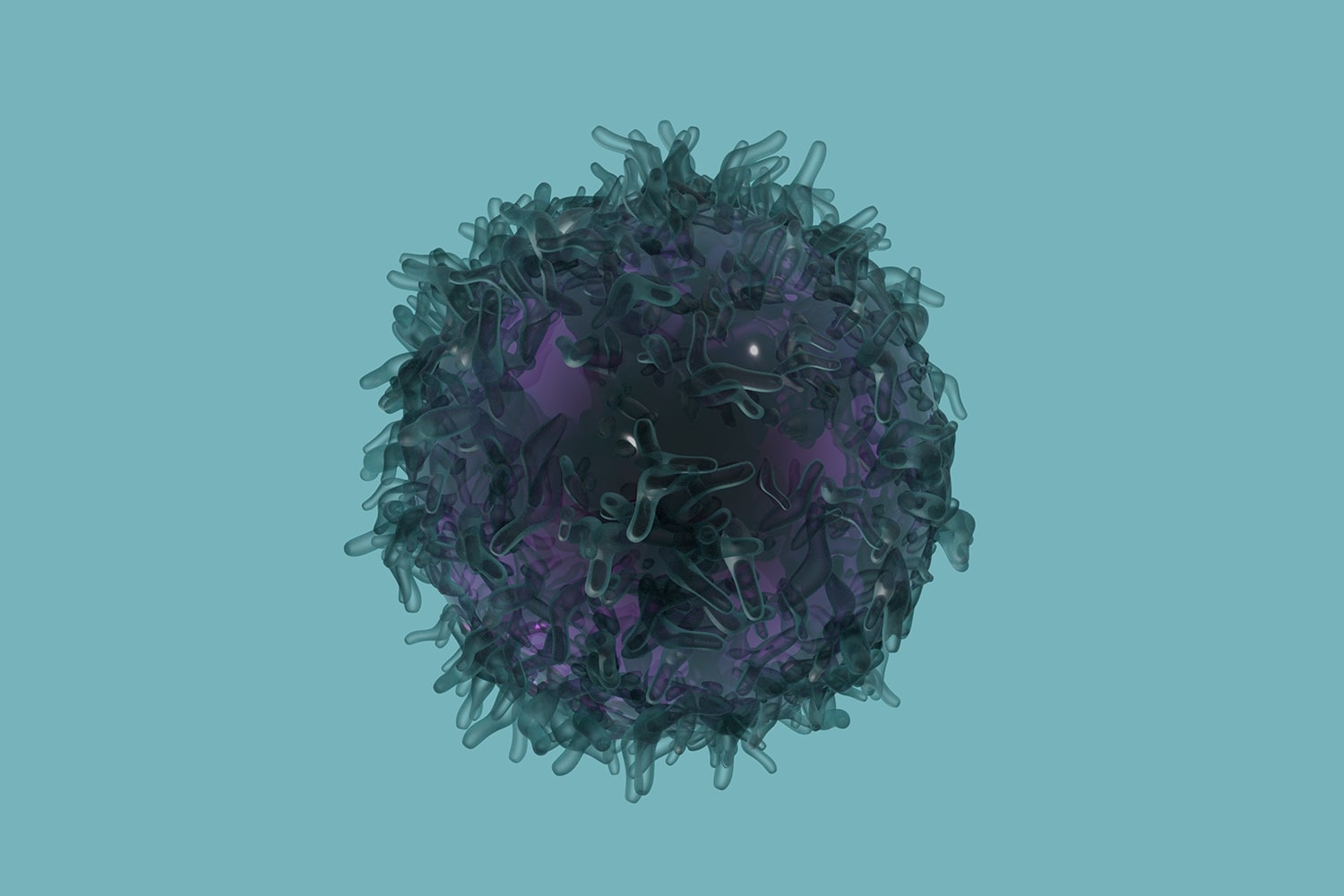

Since 2011, the FDA has approved seven immune checkpoint inhibitors, including Tecentriq, for treatment of more than a dozen other cancer types. Immune checkpoint inhibitors block proteins, including PD-L1 and its binding partner PD-1, that normally stop the immune system from attacking cancer.

About 10 to 20 percent of patients with breast cancer have triple-negative disease—a subtype of breast cancer defined by a lack of expression of either estrogen or progesterone receptor or the HER2 protein.

Cancer Today spoke with Emens about the significance of the approval and the promise and challenges of treating breast cancer with immunotherapy.

Q: Who are the patients for whom this newly approved combination immunotherapy and chemotherapy treatment is appropriate?

A: It’s particularly exciting that this is for triple-negative breast cancer, because there are almost no targeted therapy options for those patients with the exception of BRCA-mutated patients who are eligible to be treated with PARP inhibitors. The atezolizumab approval is really the first targeted therapy for a reasonable proportion of triple-negative breast cancer patients who express the PD-L1 biomarker. It is very exciting that we have a biomarker that can select patients who have a higher likelihood of benefit. It is clear from the data that patients who don’t express the PD-L1 biomarker do not derive benefit from this therapy, and so we can avoid giving this to patients who will not benefit.

Q: How will patients be tested to see if they are eligible for this regimen, and should all triple-negative breast cancer patients be tested?

A: The PD-L1 biomarker test that was also FDA-approved along with the combination therapy looks at PD-L1 expression specifically on immune cells within the tumor. The sample analyzed is either the primary tumor [in the breast] or a biopsy taken at the time of recurrence, which is the standard of care for these patients to check if anything has changed with the tumor, including expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2. Now we will also test for PD-L1.

Q: Why was this immunotherapy specifically tested in patients with triple-negative disease?

A: Triple-negative breast cancer has a major unmet need because the main therapies that we have are cytotoxic chemotherapies. These triple-negative patients are in need of more targeted approaches to managing their disease. Triple-negative breast cancer is more likely to have immune cells infiltrating the tumor … and is also more likely to have PD-L1 expression on these immune cells. The combination of these things is the rationale for focusing this immunotherapy on this subtype of breast cancer as the first group to test it in.

Q: Are there other immunotherapy approaches that are currently being studied for breast cancer?

A: Not all patients are PD-L1 positive and not all PD-L1 positive patients respond, and so we need additional immunotherapy approaches for those patient groups. There are now clinical trials that are testing additional immunotherapy approaches, most in combination with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors. The rationale is that one or a few of these combinations might be able to convert tumors that are PD-L1 or PD-1 negative into those that have immune cells infiltrating the tumor or that turn on PD-L1 or PD-1 expression. That would bring the benefit of immunotherapy to more patients. Some of these immunotherapy partners include vaccines and drugs that target other immune pathways. What makes immunotherapy particularly exciting is the potential for longer, more durable responses than those we see with standard chemotherapy. This approval is an important first step towards bringing longer responses to women with breast cancer.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.