The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) today issued new recommendations for cervical cancer screening. Cervical cancer screening allows physicians to identify precancers and remove them before they become cancerous, as well as detect early-stage cancers.

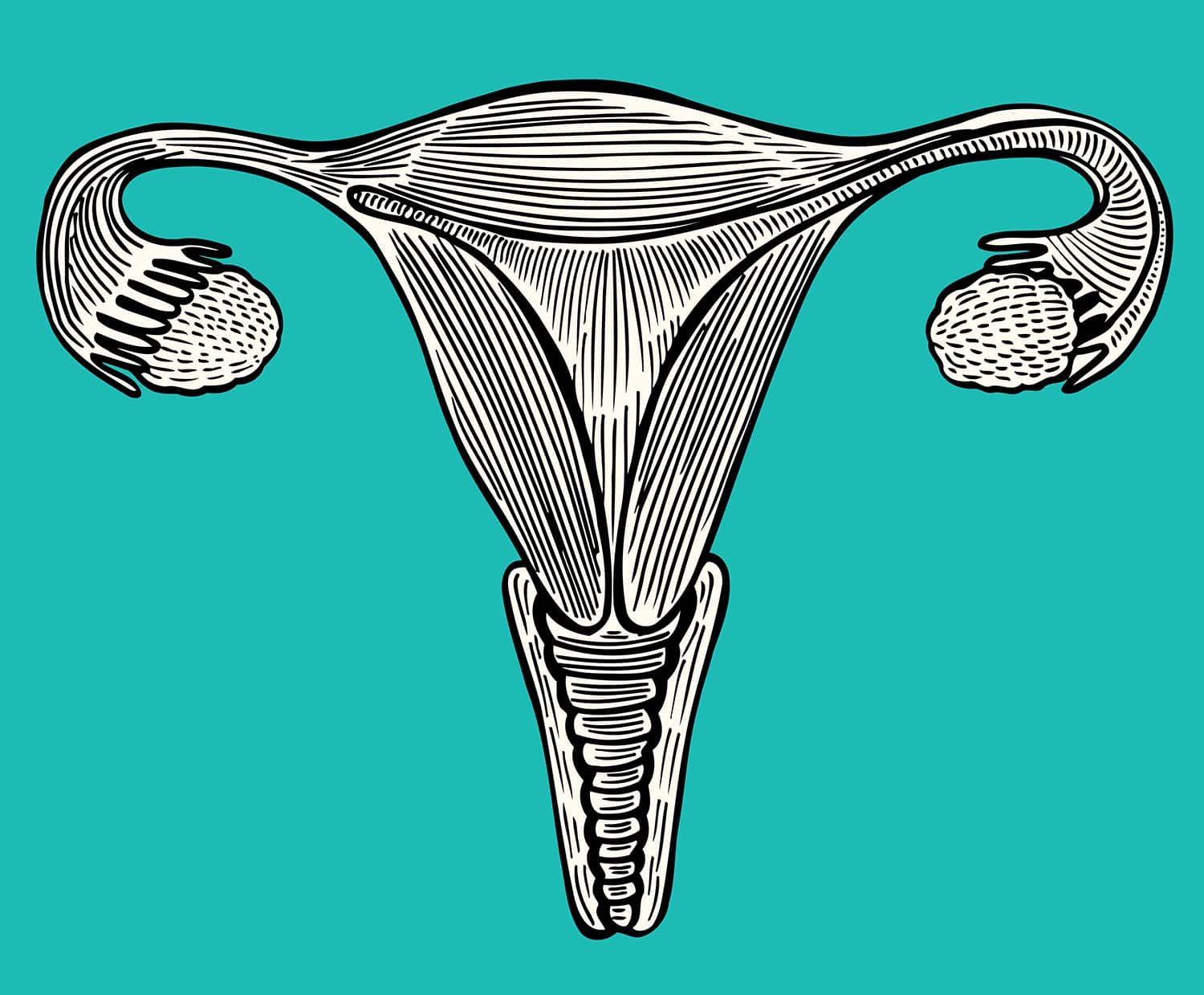

One well-known method of cervical cancer screening is the Pap test, in which cells sampled from the cervix are analyzed under a microscope for abnormalities. It’s also possible to screen for cervical cancer by testing cells sampled from the cervix for DNA from high-risk strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) that cause the majority of cervical cancer cases.

In an editorial accompanying the new guideline in JAMA, two physicians discuss the updated recommendations and the gaps in access to cervical cancer screening.

Cancer Today spoke with the authors of the editorial, obstetrician-gynecologists Lee Learman of Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton and Francisco Garcia, assistant county administrator and Chief Medical Officer of Pima County in Arizona and Emeritus Professor of Public Health at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

CT: Why is cervical cancer screening important?

Learman: Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women around the world, but nearly all cases are preventable. In the countries that have created screening programs, the rates of cervical cancer deaths have declined except in those populations that don’t have access to screening. The same is true in the U.S., where screening is highly effective in preventing cervical cancer for those who have access to it.

CT: What are the important highlights of the new guideline from the USPSTF, and how does the guideline differ from the prior one from 2012?

Learman: The 2012 guideline, for women between the ages of 21 and 29, recommended a Pap test every three years, and that has not changed in this new guideline. In 2012, for those women between the ages of 30 and 65, the task force recommended that women could either continue to have a Pap test every three years or have co-testing every five years, which means that a patient would receive high-risk HPV molecular testing and cervical cytology testing together. What is new in 2018 is that there is now a third option for this group of women, which is to only have the high-risk molecular HPV testing all by itself every five years. So for the first time, the task force has recommended a screening method for cervical cancer that does not involve a Pap test.

CT: Is this USPSTF guideline in line what other organizations recommend for cervical cancer screening?

Learman: The 2012 task force recommendations were very similar to those written by other organizations working to prevent cervical cancer, and we will have to see over time whether these other organizations will recommend something similar to the three choices that we just described.

CT: What was the rationale for the differing screening strategies for the two age groups of women? What research is that based upon?

Learman: We’ve learned over time that much of the HPV infection that is picked up in younger women is cleared on its own for those who have an intact, normal immune system. So HPV presence at a younger age doesn’t mean too much as far as developing cervical cancer, which is why the Pap test is the only option recommended. As part of their process, the task force commissioned several scholarly studies to guide the development of its recommendations. One was a systematic review of the literature and the other was a statistical decision analysis comparing the benefits and harms of the different screening approaches. Both were published in conjunction with the recommendations.

The task force routinely puts up a draft recommendation for public comment, as it did last September, and the final recommendations were modified in response to these public comments. In the first draft, there was not going to be an option of co-testing included for the age 30 to 65 group. But in response to public comments and based on the data in the decision analysis, the task force decided that they couldn’t call co-testing inferior to the option of HPV testing alone. For this and other pragmatic reasons, the task force decided to recommend all three strategies equally and to promote discussions in which patients and their clinicians weigh the benefits and harms of each option.

CT: What are the pros and cons of the different choices available for cervical cancer screening?

Garcia: The biggest difference is that screening that includes HPV testing has a higher degree of sensitivity and a better ability to identify precancer. The trade-off is that there is more HPV detection, so more women end up having follow-up procedures. Another difference is cost, in that co-testing is more expensive than either HPV [testing] or the Pap test by itself.

CT: Access to cervical cancer screening is still a major issue for some women. Who are the women that are not being screened?

Garcia: Increasing cervical cancer screening is about increasing access to services, and providing insurance coverage is a critical element. The subset of people who still get cervical cancer by and large tend to be poor women from communities of color, women who are foreign-born and those living in remote areas where services are scant. Recommendations on their own don’t fix that access to screening, and we need to continue to work on that.

Learman: To give you a sense of the magnitude of this group that is not being screened, by 2012, 10 percent of U.S. women aged 21 to 65—that is, about 8 million women—reported not being screened for cervical cancer in the past five years. That is a lot of women. The 8 million include women who have access to screening but do not see it as a priority and others who have difficulties accessing screening for financial and other reasons. There is another group who are engaged in ongoing health care but receive guideline-incongruent screening because of the variation in the use of best practice guidelines in their communities.

CT: If people increasingly receive the HPV vaccine, do you think that would affect recommended screening strategies?

Garcia: At this time, no guidelines have any modifications for those women who have received the HPV vaccine versus those who have not. Cervical cancer screening will have to evolve as there is a higher uptake of prophylactic HPV vaccination, but at this point it is too early to tell and too early to anticipate what that will look like.

Learman: The great promise of HPV vaccination in children is to create herd immunity in the population, which would decrease the prevalence of cervical cancer and reduce the intensity of screening. The current uptake of the HPV vaccine is not close to the minimum needed to achieve herd immunity, so it will be a while before we see a major difference there.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.