Brian Peguese of Indianapolis was just weeks away from his 10th birthday in November 2019 when he was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Over the following year, Peguese underwent several courses of chemotherapy and radiation, relapsing three times. “On the third time, they decided he needed to have a bone marrow transplant,” says Peguese’s mother, Juanita Perkins.

Brian Peguese (center), Juanita Perkins and Peguese’s half brother, Dontrell Segarra, visit Walt Disney World in March 2017. Photo courtesy of Juanita Perkins

A family friend connected Perkins and Peguese with the nonprofit National Marrow Donor Program, which operates the Be The Match registry. Be the Match, which was formed more than 30 years ago, was the first national registry of potential bone marrow donors and is now the world’s largest bone marrow donor registry. The family hoped to find a matching donor for Peguese, but Perkins, who works as a geriatric nurse, was not optimistic. “By us being African American, there’s only like a 23% chance of us finding a match,” she says, citing statistics provided by Be The Match.

Black, Hispanic and Asian patients tend to have a harder time finding a match on the registry compared with white patients, who have a 77% chance of finding a match, according to Be The Match spokeswoman Erica Sevilla. There are a number of reasons for this, she says.

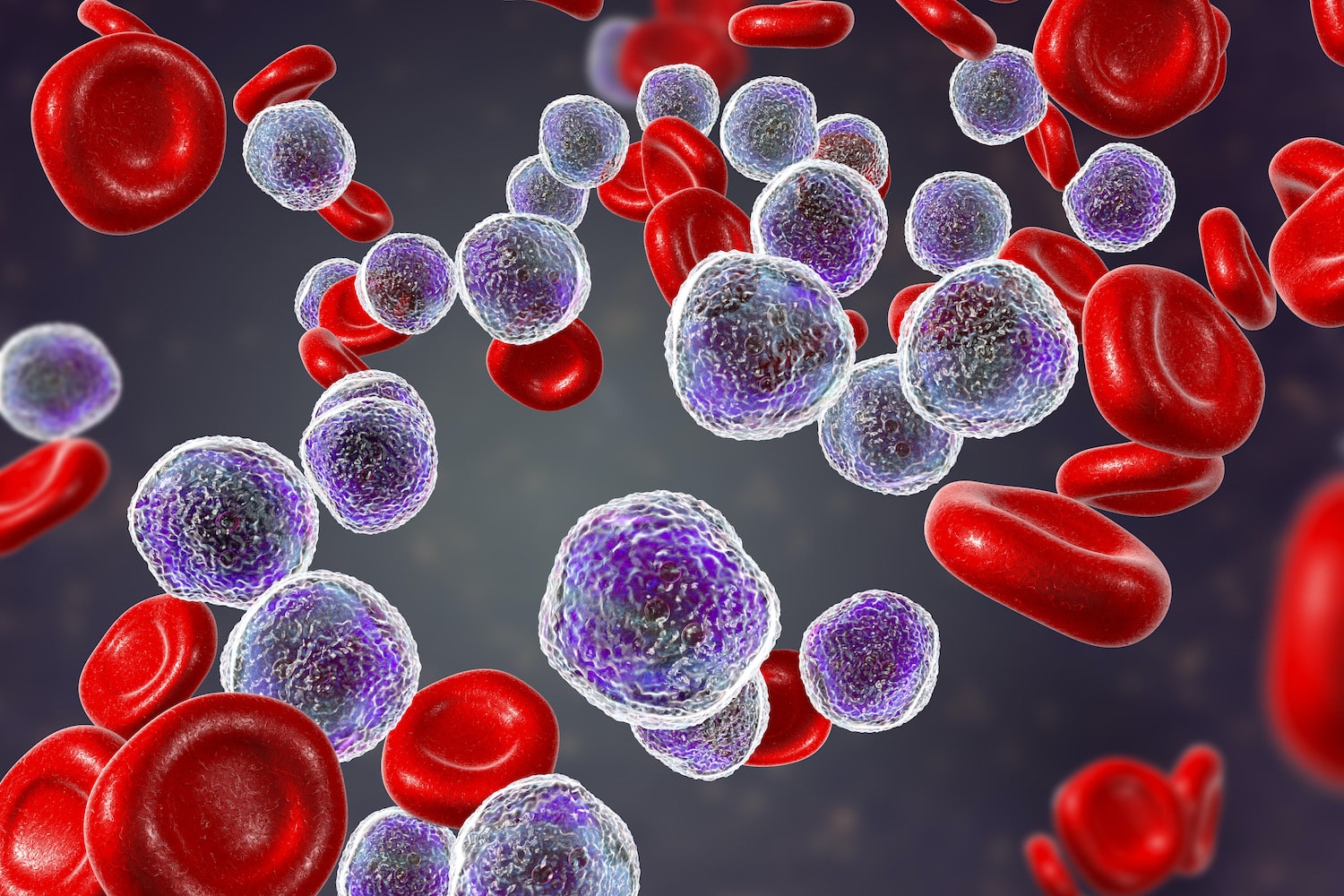

The first is the complicated biology involved in finding a bone marrow match. “What we are looking to match is much more complex than a blood type. It’s called an HLA type,” Sevilla says. HLA stands for human leukocyte antigen. HLAs are proteins found on the exteriors of most cells in the body and make up an important component of an individual’s immune system. These proteins bind and present protein fragments, including fragments from invading microbes, to immune cells, triggering an immune response. “[HLA types are] formed over generations of exposure to various illnesses within a community,” says Sevilla.

Because viruses and bacteria are constantly evolving and becoming more diverse, the HLA gene system is also diverse, according to Abeer Madbouly, the principal bioinformatics scientist at Be The Match. “You have a limited number of blood types—you know, you have A, B, O; it can be positive, it can be negative. We have millions of types of HLA,” Madbouly says. “We match on five or six of these genes. When you multiply all the possible combinations, we go into the trillions.”

Sifting through all those possible matches is important, Madbouly says, because closeness of HLA match is the most important factor for transplant success. In a transplant, the hope is the implanted section of donated bone marrow, known as a graft, will produce new immune cells to attack cancer cells. With every HLA mismatch, the odds grow that residual immune cells in the patient’s body will attack the graft, causing graft rejection. A mismatch also increases the chances of graft-versus-host disease, where the new immune cells produced by the graft attack the patient, or host.

Living in different geographic regions exposed people to different pathogens over the millennia, leading to different ethnic HLA types, according to Madbouly. It’s generally easier to find matches between people who share a similar background. “The people who are the most difficult to match for are those who are multiethnic,” Madbouly says. “African Americans are usually a mix of African and European, so [they are] very, very diverse.”

But diversity of HLA types doesn’t fully explain why it’s so difficult for African Americans to find a match on the registry. There are also simply fewer African Americans than white people signed up as donors. “Once they told me we would need a donor, I knew he was not going to find a match,” Perkins says of Peguese.

Only 4% of the 22 million people on the Be The Match registry are African American, according to Sevilla. “We believe a lot of it is the result of historical and present-day systemic racism that occurs, especially related to the medical care of African Americans,” Sevilla says. She says Be The Match believes it’s important to acknowledge that history, from the Tuskegee syphilis study, where researchers misled participants about the purpose of the study and withheld treatments, to the reliance of medical research on cell lines derived without consent from an African American woman, Henrietta Lacks. “We have a lot of work to do,” Sevilla says.

Be The Match has developed a college campus recruitment strategy as one way to reach out to a more diverse array of people, Sevilla says, though the COVID-19 pandemic has temporarily disrupted those plans. But some of the key players in getting the word out about the importance of becoming a donor are patients and patient family advocates like Perkins. “We were featured on a few news stations here in Indianapolis, so I have been trying to get the awareness out there as much as possible,” she says. Perkins also spoke with People magazine about Peguese’s story.

While Perkins’ outreach has also been hindered by COVID-19, she has still been successful, according to Sevilla. “Brian’s story resulted in nearly 1,000 people starting the process to join the Be The Match registry,” Sevilla says. Since approximately one in 430 donors will go on to donate to a patient, she says, that “statistically speaking means he helped to save two patients’ lives.”

Brian Peguese and Dontrell Segarra in Indianapolis in 2018. Photo courtesy of Juanita Perkins

While Peguese wasn’t able to find a match on the registry, it turned out his 19-year-old half brother, Dontrell Segarra, was a haploidentical, or half, match, which is very unusual in a half sibling. (Haploidentical matches are usually full siblings or parents.) “I knew it was going to happen,” Segarra says. “One day I was just sitting at my desk doing my work, and I was just thinking, ‘the match is going to be me.’”

Segarra and Peguese successfully underwent transplant surgery on Jan. 6, 2021, and are both doing well in their recovery. Before the transplant, Peguese often had difficulty speaking and felt drained. Now he is himself again, according to Segarra. “He has some energy. He’s talking way more now. It’s great to see him do all these types of things he wants to do.”

Now Perkins has another story to tell when trying to educate others about the importance of registering as a bone marrow donor. Segarra was initially nervous about the surgery, Perkins says, and it took him some time to recover. But now that it’s over, “He’s happy that he’s done it. He’s happy that he saved his little brother’s life,” she says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.