FROM HIS FIRST appearance at age 22 on the new Western Bonanza in the fall of 1959, Michael Landon was a constant presence on television for more than three decades, appearing in long-running series like Bonanza, Little House on the Prairie and Highway to Heaven. Landon won over the hearts of many viewers by playing salt-of-the-earth, steadfast characters like his most celebrated role, Charles Ingalls on Little House. Landon was more than an actor, however. Later in his career, he was a writer, producer and director on programs wholesome enough for the entire family to watch together.

“If you look at television now, there is nothing like what he loved to do and what he created,” says Susan McCray, a longtime friend who was casting director for many of Landon’s productions. “More often than not, I hear people say, ‘I wish I could sit down with my family and watch a show that makes me feel good and makes me laugh.’ ”

Landon’s career and life took an unexpected turn in April 1991 when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Shortly after the diagnosis, he invited reporters to his 10-acre ranch in Malibu, California, to break the news. He was upbeat and cracked jokes throughout.

“I think you have to have a sense of humor about everything,” Landon told reporters at the April 8 press conference when he went public with his illness. “I don’t find this particularly funny, but if you’re going to try to go on, if you’re going to try to beat something, you’re not going to do it standing in the corner.”

Childhood Conflict

Landon was born Eugene Maurice Orowitz on Oct. 31, 1936, in the borough of Queens in New York City. His father, Eli Maurice Orowitz, was a publicist and radio announcer; his mother, Peggy O’Neill, was a Broadway showgirl. His parents were frequently at odds.

“He told the story about how his mom would never speak to his father and vice versa,” says McCray. “Mike used to tell me he had a place that he would go to, and he would act out certain things. He’d pretend or he’d think of stories or ways to escape.”

When he was 4 years old, the family moved to Collingswood, New Jersey, near Philadelphia. As one of the few Jewish children in the neighborhood, young Orowitz was often on the receiving end of anti-Semitic comments by peers. In addition, he lived in constant fear of what his mother, who frequently threatened to kill herself, would do next. Landon used his experiences with his mother as the basis for a 1976 made-for-television drama he wrote and directed, called The Loneliest Runner. The movie tells the story of a bed-wetter who becomes a track athlete and competes in the Olympics. Landon himself was a bed-wetter until his early teen years; his mother hung urine-stained sheets out the window in an effort to embarrass him and make him stop.

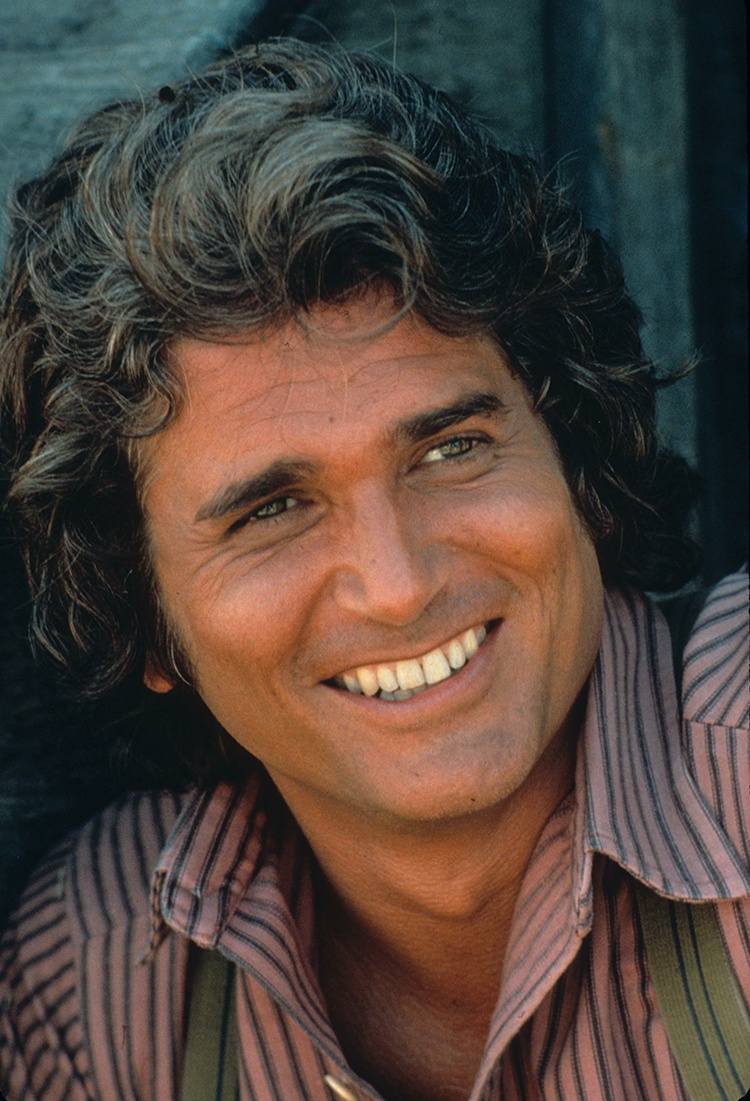

Michael Landon Photo © Zuma Press, Inc. / Alamy

In his freshman year of high school, Landon discovered he had a talent for javelin throwing. He worked hard at perfecting his skill and earned a track and field scholarship to the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Unlike the character in The Loneliest Runner, Landon’s real-life dreams to compete in the Olympics were dashed by an elbow injury. He dropped out of college at the end of his freshman year, remained in Los Angeles and took jobs selling blankets door to door, working at a ribbon factory and loading freight cars.

One day, Landon was helping a friend go over lines for an audition. The scene called for a young soldier to cry, but his friend had trouble sobbing on command. Landon’s tears came easily.

“It was the first time I had ever tried anything like that,” he said. “And I suddenly realized that it was a great release for me. I could cry when I was someone else and get a lot of things out of my system that I couldn’t get out on my own.”

An Actor Comes of Age

Landon enrolled in an acting school at the Warner Brothers studio and picked the screen name Michael Landon from a phone book. His big break came when he landed the lead role in the 1957 horror film I Was a Teenage Werewolf. His portrayal of Tom Dooley in the Western The Legend of Tom Dooley in 1959 caught the eye of writer and producer David Dortort, who recruited Landon to co-star in Bonanza. The show featured the Cartwrights—a father and his three sons who lived and worked on the Ponderosa ranch. Landon played the youngest son, Little Joe. Bonanza ran for 14 seasons through 1973 and had consistently high ratings.

Michael Landon holds actress Lindsay Greenbush, part of his TV family on Little House on the Prairie. Standing are co-stars Karen Grassle and Melissa Gilbert. Seated is Melissa Sue Anderson. Photo © Silver Screen Collection / Getty Images

In 1974, Landon moved on to star in Little House on the Prairie, another Western, this one with a family focus. He played Charles Ingalls, called “Pa” by the Ingalls children, as a hardworking and honest family man and farmer in Walnut Grove, Minnesota. Landon wrote, directed and produced many of the episodes of the series, which was inspired by Laura Ingalls Wilder’s popular Little House books. The series aired for nine seasons, ending in 1983.

After Little House ended, Landon created his own television series, Highway to Heaven, which aired from 1984 to 1989. He played Jonathan Smith, an angel on probation who traveled the country doing good deeds. By this time, Landon had started his own company, Michael Landon Productions.

He effortlessly switched hats behind and in front of the camera, recalls his wife, Cindy Clerico. “He was absolutely a genius,” she says. “He would actually be directing, they would be setting up a shot, doing the lighting, and he was sitting in his chair writing. I was in awe of him, truthfully. I’d think, ‘How does he do it? How does he handle it all?’ ”

Clerico, who was a stand-in for actress Melissa Sue Anderson on Little House, married Landon in 1983, becoming his third wife. In all, Landon was father to nine children: two adopted children from his first marriage to Dodi Levi-Fraser, one stepdaughter and four biological children from his second marriage to Marjorie Lynn Noe, and two more with Clerico.

Genomic analysis may provide new treatment options.

by Marci A. Landsmann

Real-Life Drama

In 1991, Landon was hard at work on a new television series called Us. Scheduled to air in the fall, the series would feature Landon as a man wrongly convicted of a crime who is released from prison following an 18-year sentence. After wrapping up production for the show’s pilot, Landon decided to take Clerico and their two children skiing in Park City, Utah. He had been experiencing stomach discomfort for weeks, but during the ski trip, the pain became so unbearable that he flew home to see a doctor.

Michael Landon attends a 1989 fundraiser in Malibu, California, with his wife Cindy, daughter Jennifer and son Sean. Photo © Ron Galella / Getty Images

Once home, he had a computerized tomography (CT) scan, which revealed a large tumor in his abdomen. Landon broke the news by phone to Clerico, who came home with the children to Malibu. A few days later, Landon got results from a biopsy performed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles that revealed he had inoperable pancreatic cancer that had spread to his liver.

Despite reservations, Landon agreed to be treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a common chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer at the time. He received the treatment only once because he didn’t like putting chemicals in his body for a treatment he felt had a low chance of success. Landon sought out a doctor who recommended a holistic treatment, including vitamins, carrot juice and coffee enemas. He felt stronger on the holistic regimen and his stomach pains subsided, but when he went back for another CT scan on April 24, Landon learned his cancer had doubled in size and spread elsewhere in his body in less than three weeks.

“At that point, we were looking at him not being here, and I think he knew,” Clerico recalls. “That was a tough day.”

More Options

The National Cancer Institute estimated that more than 53,000 people in the U.S. would be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and more than 41,000 would die of the disease in 2016. While pancreatic cancer accounts for just 3 percent of all cancer cases in the U.S., it is responsible for about 7 percent of all cancer deaths. The vast majority of pancreatic cancer cases are diagnosed after the cancer has spread to other areas of the body such as the liver, the abdominal lining or the lungs, which eliminates surgery as a possible cure.

Since Landon’s death, the long-term survival rate has doubled. Still, just 8 percent of people with pancreatic cancer live five years or longer, based on data collected through 2012, up from 4 percent between 1990 and 1992. Despite these numbers, researchers and physicians point out several positive trends in treating the disease.

The combination of Gemzar (gemcitabine) and Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel), two chemotherapy drugs, has become a standard of care for patients with pancreatic cancer. Gemcitabine was first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in 1996, and Abraxane was added to the regimen in 2013 after studies showed the two drugs used together increased median survival to seven months from four months when treated with 5-FU alone. While the majority of patients lived just months longer, 35 percent of patients on this combination lived a year or longer, according to 2013 data, compared to data published in 1997 that indicated just 2 percent of patients treated with 5-FU lived at least a year.

In 2011, researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that another combination, called FOLFIRINOX, which adds leucovorin, Camptosar (irinotecan) and Eloxatin (oxaliplatin) to 5-FU, increased survival from 7 months to 11 months compared to treatment with Gemzar alone, though patients experienced more toxicity from this combination, including chemotherapy-related infections.

“These options took an average patient who would die in three to four months and doubled survival to eight to 10 months,” says medical oncologist Elizabeth M. Jaffee, who studies new treatments for patients with pancreatic cancer at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center in Baltimore. She notes that many patients taking these drugs live more than a year, which gives them more time to avail themselves of experimental therapies.

For example, researchers are using genomic analysis of pancreatic cancer tumor samples to guide new treatment choices. Molecular biologist Lynn Matrisian estimates that approximately 25 percent of pancreatic cancer patients have tumors with genetic mutations that could respond to targeted drugs.

“This gives us additional guidance as to what might work for that patient, and that’s better than not knowing anything or saying [to a patient], ‘There isn’t anything we can do,’ ” says Matrisian, chief science officer at the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, a research and advocacy organization based in Manhattan Beach, California.

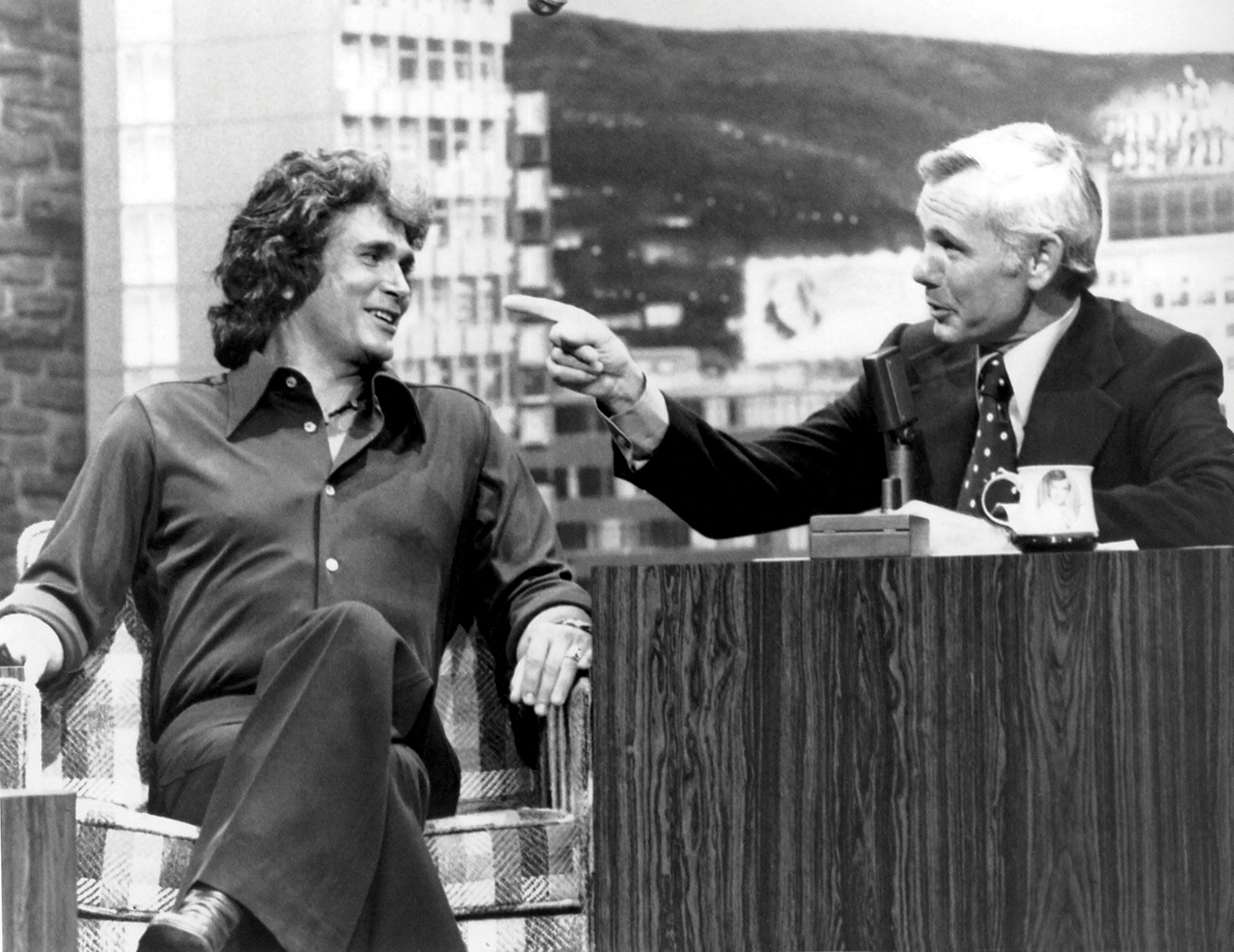

Michael Landon appears on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in the mid-1970s. Landon and Carson were friends, and Landon talked about his cancer diagnosis during his last appearance on the show in 1991. Photo © NBC / Getty Images

In the months following his diagnosis, Landon continued to use humor to put people at ease despite his prognosis. During a May 9, 1991, appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, Landon joked about getting his roots done (Landon had prematurely graying hair) and his regimen of coffee enemas and carrot juice. He chose to spend most of the time that remained with his family. On the weekend before his death, all nine of his children kept vigil with Clerico at their home. Landon died July 1, 1991, with Clerico by his bedside.

The enduring appeal of Landon’s brand of wholesome entertainment is evident in the fact that reruns of Bonanza and Little House are still broadcast and continue to draw an audience.

“In all of his programming, Michael wanted people to be happy and to relate and feel something in their hearts,” says McCray. “Everyone felt something when they’d watch a Michael Landon show. Every time.”