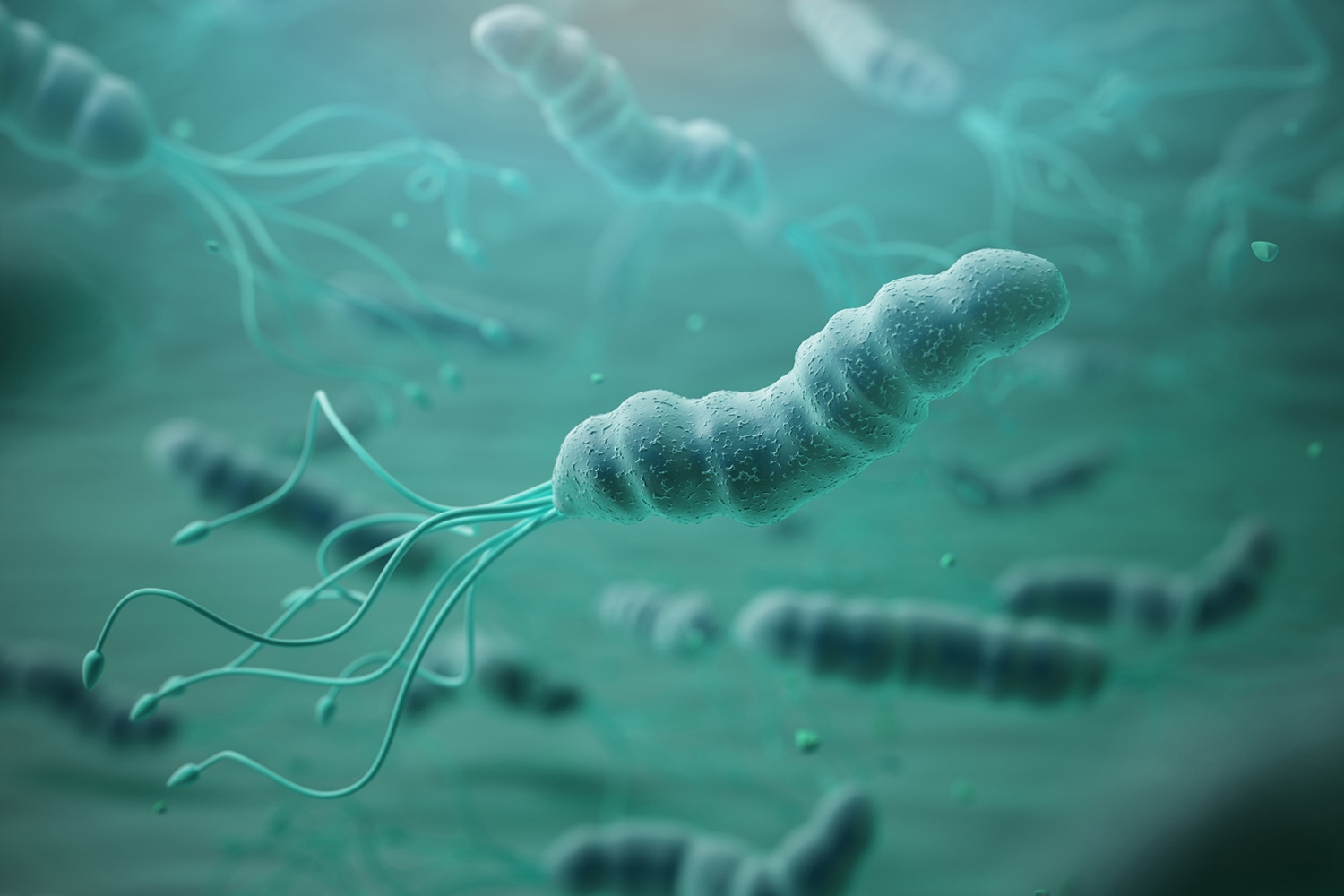

More than half of the world’s population is infected with the stomach bacteria Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). In most people, the infection causes no problems. Yet, H. pylori is also the primary known cause of stomach cancer. A recent study that looked at dramatically different stomach cancer rates in two regions of Colombia suggests why the bacterium is riskier for some people—and may help identify those most at risk.

The researchers analyzed stomach biopsies and blood samples from more than 200 Colombians and performed genetic tests to trace their ancestry as well as the ancestry of the strain of H. pylori they carried. About half the participants lived in the mountains and about half lived on the coast. Both regions have similar H. pylori infection rates (about 90 percent), but the rate of stomach cancer is 25 times higher in the mountains.

The findings, published in the January 28 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that the people living on the coast were primarily of African descent, and that their H. pylori strains were predominantly derived from Africa. In contrast, the majority of people living in the mountains were of Amerindian ancestry, and many of them had strains of H. pylori likely to have been acquired from Spanish colonizers in the 16th century. These strains may have displaced the strain the Amerindians originally carried, says Barbara Schneider, a molecular biologist at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., who co-authored the study.

In the people living on the coast, “the pathogen and the host have made peace with each other,” says Schneider. “Whereas, [in the mountains] the Amerindians and the bacterium that came with the conquistadores have not had [enough] time for that to happen.”

Sarah Tishkoff, a population geneticist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, says, “This [study] is a beautiful example of co-evolution between pathogen and human host and how the two can influence disease susceptibility. People are starting to realize more and more that the bacteria in bodies are having an impact in many ways in terms of our health and our susceptibility to disease.”

Schneider hopes the study’s findings will help doctors in Colombia identify which patients are more likely to have their H. pylori infection put them at risk of developing stomach cancer. “You can’t treat a whole country with antibiotics,” she says. “All [that would] do is generate antibiotic-resistant strains.” But perhaps more doctors will now determine which of their patients should undergo an endoscopy, Schneider says, and, based on the results of the procedure, which ones should be treated.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.