Two fundamental questions about any cancer are: How many people survive it? For how long? Survival statistics answer those questions. “They’re certainly important to people who are diagnosed so they know what their prognosis is,” says Kathy Cronin, a scientist with the Surveillance Research Program at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Survival statistics often stand in as proxies for the deadliness of a disease. But such statistics can be as confusing as they are encouraging or sobering. Cancer Today spoke with Cronin and Kim Miller, a surveillance researcher at the American Cancer Society, about how to interpret these survival numbers.

What Is Relative Survival?

If you spend much time reading about cancer, you’ve probably seen the term “five-year relative survival,” whether on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program website, on the website of the American Cancer Society, or in scientific papers or media reports. But what does the “relative” part in five-year relative survival mean? “I think relative survival is hard to understand and is often misunderstood,” Cronin says.

Relative survival describes the percentage of people expected to survive the effects of their cancer, absent other causes of death, for a given number of years following a cancer diagnosis. It’s calculated by taking observed survival—the proportion of people with a given cancer who are alive a certain number of years after their diagnosis—and dividing that number by expected survival—the proportion of people in a comparable cancer-free group expected to survive that long.

Dividing observed survival by expected survival “adjusts the survival statistic for the fact that people may die from other causes” after they have been diagnosed with cancer, Miller says. “Many cancer patients specifically want to know the probability of surviving cancer, and they’re not interested in their survival with regard to other causes of death.”

What Relative Survival Is Not

Five-year relative survival is not the percentage of people who are still alive five years following a cancer diagnosis. That’s observed survival. Depending on the situation, relative and observed survival can be quite similar—or not.

Relative survival and observed survival are most similar in populations for whom expected survival is high, such as in younger age groups, according to Miller. “When you have a much higher expected survival, the observed and the relative are going to be very similar because you’re just not going to be adjusting for that many other causes of death,” she says. “If there was absolutely no other-cause mortality, [observed and relative survival] would theoretically be the same,” Cronin adds.

Relative and observed survival are most different when the likelihood of dying from other causes is high, such as in older populations, according to Cronin. An extreme example of this difference, she says, comes from survival statistics for men age 80 and up who were diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer between 2010 and 2014. Five-year relative survival for that group is 99.9%. The sky-high relative survival doesn’t mean that these cancer patients are nearly guaranteed to live five years past their cancer diagnosis, though. “It just means they will not have died of their prostate cancer, in the absence of other causes,” Cronin says. Indeed, the observed survival for that group, or the percentage alive five years following diagnosis, was 59%. The five-year expected survival for a cancer-free cohort of men in this demographic was also about 59%, Cronin says, which accounts for the 99.9% relative survival of the prostate cancer group. She explains that since the chances of surviving prostate cancer are so high, most prostate cancer patients in this demographic die of other causes.

Patients may also hear the term overall survival, which is a statistic often used when reporting the outcomes of clinical trials. Overall survival is defined as the length of time patients live after starting a specific treatment (or after being randomized to a treatment or standard care in a clinical trial) or after diagnosis.

Where Do the Underlying Data Come From?

Observed survival data come from population-based cancer registries, such as the SEER Program of the NCI. Individual SEER registries, each covering a specific geographic area, collect data about each person diagnosed with cancer, including their tumor type and stage at diagnosis, initial treatment, and outcomes, including cause of death and survival time. Each registry reports its data, from which patients’ identifying information has been removed, to the SEER Program headquarters at the NCI, where the data are analyzed and made available to researchers. Expected survival data come from what are called life tables, which are produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Life tables estimate, out of a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 people in the U.S. population, the number expected to survive to each age. They can also be used to predict the chances of surviving from one age to another, which is needed to calculate the likelihood of a cancer-free population surviving five years.

You might notice that expected survival is defined as survival for a cancer-free cohort, yet the U.S. population—the population covered by life tables—certainly includes cancer patients. Statisticians don’t consider this to be a problem because deaths from cancer—and especially an individual cancer type—make up a small proportion of total deaths in the U.S. population. Expected survival for people without cancer is considered to be roughly the same as expected survival for the entire population.

Another Way to Calculate Chances of Surviving Cancer

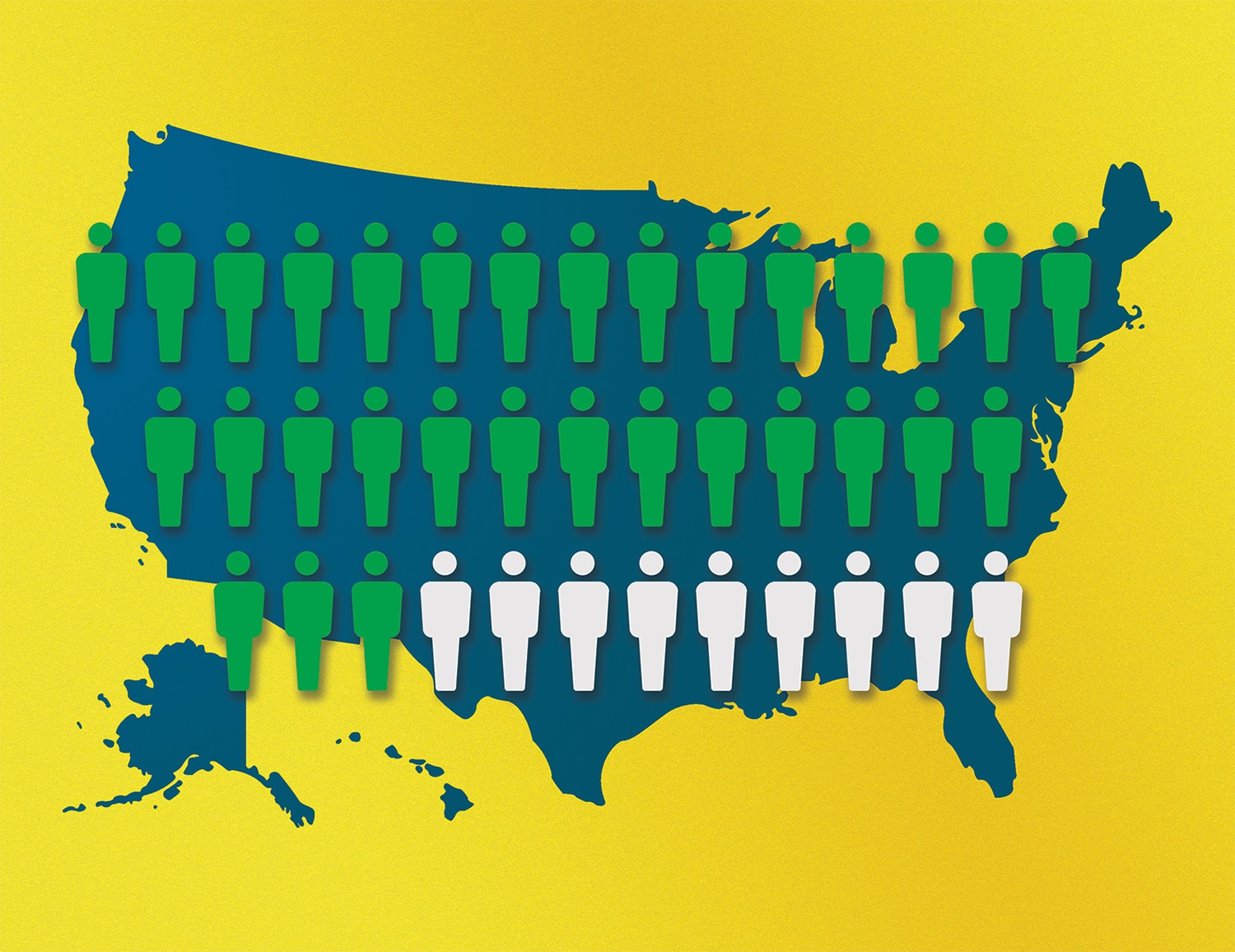

Life tables, the source of expected survival data, do not reflect all populations. These tables are currently only available for white, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic populations in the U.S., and life tables for the U.S. Hispanic population have only been available since 2006, Miller says. These tables are not available at all for people of Asian/Pacific Islander or American Indian/Alaska Native heritage. In sum, life tables and relative survival statistics based on them are most accurate for white people, Miller says. “Other racial/ethnic groups are not represented well by these statistics,” she continues. Yet determining survival statistics for different racial and ethnic groups is important, Miller says, both to provide information to all cancer patients and also in order to document disparities in cancer survival between racial and ethnic groups.

When life tables aren’t available, statisticians will use a different statistic, called cause-specific survival. Cause-specific survival relies on cause of death information recorded on death certificates to determine how many people in a given cohort died from their cancer and, therefore, how many are surviving it. This statistic depends on the quality of cause of death information recorded on death certificates, which is a limitation, Miller says. For example, people who died of rectal cancer are often misclassified as having died of colon cancer on death certificates. For that reason, it’s difficult to accurately estimate cause-specific survival for colon and rectal cancers separately. Instead, they are lumped together as “colorectal cancer.” “Relative survival doesn’t depend as much on the quality of death certificate information, so you can go get at the differences in colon cancer survival versus rectal cancer survival using specifically relative survival,” Miller says.

A Grain of Salt

Miller advises patients to interpret any survival statistic, be it relative survival or cause-specific survival, with caution. “Because survival statistics are usually calculated using population-based data, that means that a specific survival statistic may not apply specifically to a specific patient,” she says. Factors that can affect an individual’s prognosis include smoking status, physical activity, diet, access to health care and characteristics of an individual’s cancer. “It’s really important for individual patients to talk to their doctors about their specific prognosis and to use any population-based cancer statistics with a grain of salt,” Miller says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.