CAR-T Cell Therapy in the Clinic

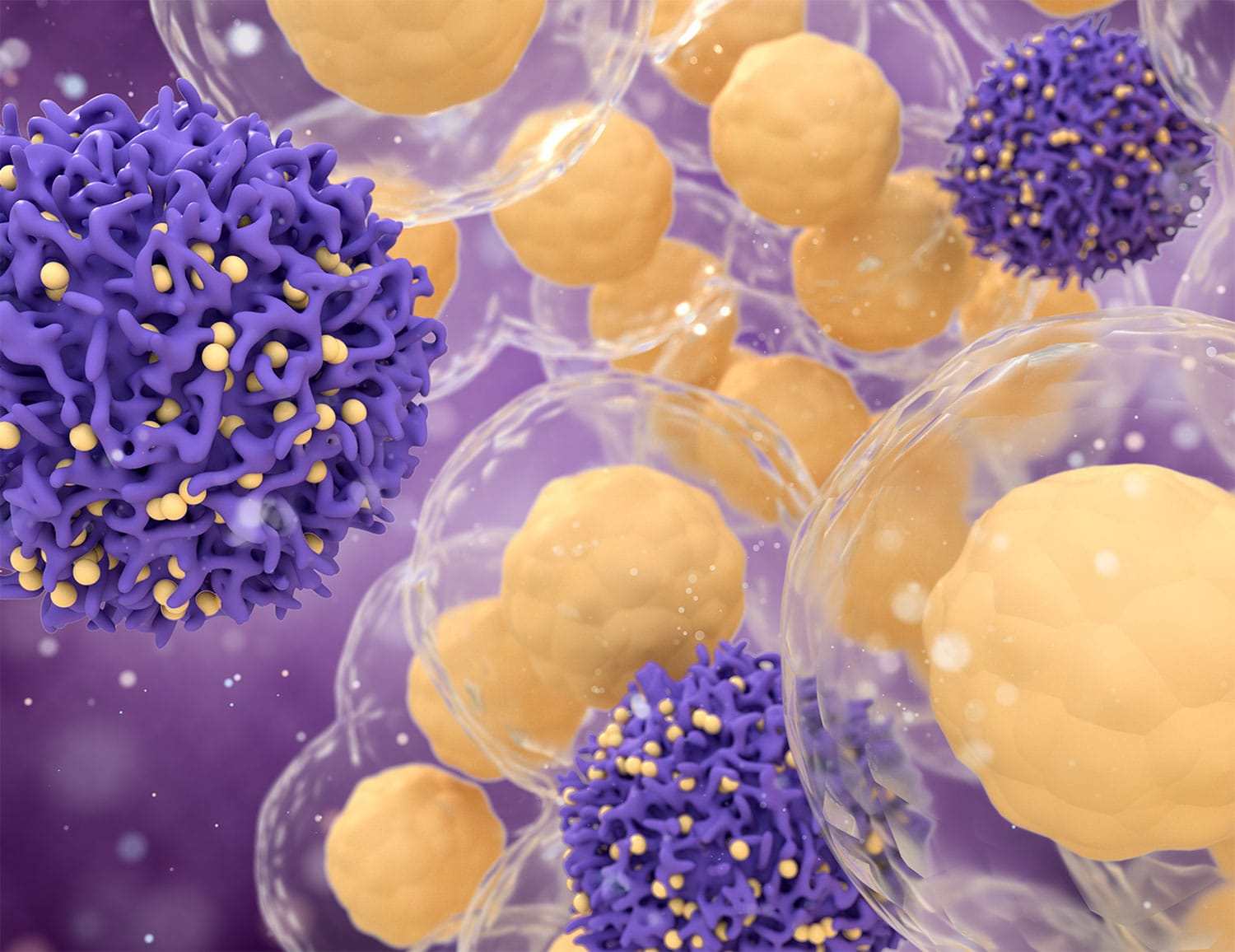

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first CAR-T cell therapy in August 2017 and a second in October 2017 for some patients with leukemia and lymphoma. Now, patients are receiving these approved CAR-T cell therapies in more than 100 U.S. hospitals, writes Ilana Yurkiewicz, a physician at Stanford University, in an article published Oct. 23 in Undark. Yurkiewicz discusses what it is like to be a physician caring for patients receiving CAR-T cell therapy and interviews an early CAR-T patient and her partner about their experience. CAR-T cell therapy can offer a chance at survival to patients who have not responded to other treatments, but patients can develop life-threatening side effects, including neurologic side effects “ranging from headaches to difficulty speaking to seizures to falling unconscious,” Yurkiewicz writes. Most patients do not have long-term problems after these neurologic side effects, but some do. Physicians must learn how to deal with these new side effects, building networks of experts who can advise each other.

Communicating About Survival

Many cancer clinical trials measure success by length of progression-free survival (PFS)—a term defined as the time it takes after starting a treatment for a patient’s cancer to grow a certain amount or for a new tumor to appear. An article by Mary Chris Jaklevic published Oct. 22 by Health News Review discusses how news coverage of studies using PFS can be misleading, citing stories that say treatments increased survival when they only increased PFS. “Despite including the word ‘survival,’ the term PFS doesn’t indicate how long patients will live,” Jaklevic writes. PFS is poorly correlated with overall survival and quality of life, according to some studies, and it’s possible for a drug to increase PFS while decreasing patients’ length of life.

The Cost of Lymphedema

Some cancer treatment can lead to lymphedema, a condition in which lymphatic fluid builds up in a patient’s limbs. Treatment includes wearing compression garments that help reduce swelling. But some patients struggle to pay for these garments, according to an article published Oct. 23 by Kaiser Health News. Medicare does not cover compression garments, Medicaid offers some coverage and coverage by private insurers is variable. These garments must be regularly replaced, and some patients require expensive custom garments. Federal and state laws mandate some coverage of these garments, but they do not apply to everyone who needs lymphedema care, and sometimes coverage is limited.

An Expanded Ovarian Cancer Approval

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Oct. 23 expanded approval of the targeted therapy Zejula (niraparib) to a wider group of patients with ovarian cancer. The drug was already approved as a maintenance treatment for people with recurrent ovarian cancer who have responded to platinum-based chemotherapy. The new approval is for patients with advanced ovarian cancer who have tried three previous chemotherapy regimens and who have cancer associated with a biomarker called homologous recombination deficiency (HRD). Homologous recombination is a pathway cells use to repair damaged DNA, and cells that have problems with this repair pathway are more likely to respond to PARP inhibitors like Zejula.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.