TALL AND IMPOSING, Edward Herrmann was a versatile actor who honed his craft onstage, in films and on television. He is perhaps best known for playing Richard Gilmore, the wealthy father and grandfather in the Gilmore Girls TV series.

Blessed with a mellifluous voice, Herrmann also had an impressive career as a voiceover artist. He narrated more than 300 audiobooks as well as shows on the History Channel and PBS, including lending the voice of FDR to Ken Burns’ documentary The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. His final narration project was for the documentary Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies.

Those who knew Herrmann well remember him fondly. “Ed was a kind and decent man and never had a negative thing to say about anyone,” says Robbie Kass, the actor’s agent and manager for more than 25 years. “He gave everyone he met respect and got it back tenfold.”

Kass should know. He and Herrmann traveled the world together for openings and publicity events. “Wherever we went, he would strike up conversations with people he met,” recalls Kass. “He was oblivious to status or position and interested in talking to everyone, from bike messengers to businessmen. People opened up to him like they were old friends.”

When Herrmann returned from his travels, he liked nothing more than to settle into his Salisbury, Connecticut, home, which he shared with his wife, Star, and the family’s many pets. His grown children, son Rory, a chef in Los Angeles, and daughters Ryen, a merchandising manager with the clothing company Patagonia, and Emma, a college student, were frequent visitors. The family especially enjoyed festive Christmas celebrations together. “His kids were everything to him,” says Star. “He was a wonderful father and always made family a priority.”

But work was a passion, too. From his 1972 Broadway debut in the comedy Moonchildren to his success playing Roosevelt in Eleanor and Franklin and Eleanor and Franklin: The White House Years, to parts in numerous films, including The Paper Chase, Herrmann lent his charm and talent to a wide array of roles, giving him recognition and a solid career.

On the top of the list is Gilmore Girls, the television series that ran from 2000 to 2007, featuring Herrmann as the father of Lorelai (Lauren Graham) and grandfather of Rory (Alexis Bledel).

Herrmann expected to continue acting and narrating films indefinitely, but on Dec. 6, 2013, he had a seizure while riding a train from New York City to Wassaic, New York, near his home in Salisbury. Soon after, Herrmann was diagnosed with grade IV glioblastoma, the most common and deadliest type of malignant brain tumor among adults.

College Marks a Turning Point

Edward Herrmann was born in Washington, D.C., on July 21, 1943. Soon after, his family moved to Grosse Pointe, Michigan, where his father, John Anthony Herrmann, an engineer, worked in Detroit’s booming automobile industry and for railroad companies. His mother, the former Jean O’Connor, was a homemaker.

Herrmann attended Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he developed close relationships with some of his professors who “inspired him to read and learn,” says Star.

Photo © AF Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

During his college years, Herrmann fell in love with the theater. After graduating from Bucknell in 1965, he joined the Dallas Theater Center in Texas, where he spent four theater seasons between 1965 and 1970 honing his acting skills. Encouraged by his mentors, he made his way to New York City in 1970.

After his 1972 Broadway debut, Herrmann appeared in several other Broadway productions. He won a Tony Award in 1976 for his performance as Frank Gardner in George Bernard Shaw’s play Mrs. Warren’s Profession. Other Broadway shows included the 1980 revival of The Philadelphia Story, with Blythe Danner, and Plenty, in 1983, for which he received a second Tony nomination.

Among his film credits are a minor role in The Great Gatsby (1974); a part in Reds (1981) featuring Herrmann as journalist John Reed’s friend and editor, Max Eastman; and Richie Rich (1994), where he played the father of the richest kid in the world. He also portrayed the headmaster in The Emperor’s Club (2002) with Kevin Kline.

But he might have made his biggest mark on television. “The writing was better on television than in films, and the parts were juicier,” says Kass.

The many parts Herrmann played on television included a recurring role as Father Joseph McCabe on St. Elsewhere, for which he received two Emmy nominations; an Emmy-winning role on The Practice as an attorney accused of a crime and incarcerated; and the flawed but endearing Richard Gilmore, whose gruff manner belied the kind-hearted man underneath. More recently, he played Lionel Deerfield on The Good Wife from 2010 to 2013.

Signs of Trouble

About a year before Herrmann’s diagnosis, Star began noticing behavior changes in her typically calm, easy-going husband. “He was moody and got upset easily,” she says. “He would get so mad at me. I couldn’t imagine what I had done.”

Herrmann had a particularly explosive outburst at the end of November 2013, right before Star and Ryen traveled to California to spend time with Rory’s baby girl. They heard from him while they were away and he seemed well.

During the long flight home a few days later, Star and Ryen turned off their cellphones. When they arrived in New York City, they both had phone and text messages from the hospital in Sharon, Connecticut.

The news wasn’t good. Herrmann had suffered a grand mal seizure—which can cause muscle contractions and a loss of consciousness. An MRI of his brain revealed a large tumor in the right frontal lobe, the part of the brain responsible for mood regulation, memory and reasoning.

“The tumor explained his explosive anger at me two weeks earlier,” Star recalls. “The tumor in his brain was causing so much pressure that it was like a volcano waiting to burst. With the seizure, it finally did.”

Herrmann needed surgery as soon as possible. The family selected neurosurgeon David Kvam to perform the difficult operation at Hartford Hospital in Hartford, Connecticut. As is standard practice, Kvam used stereotactic computer navigation to guide him during the delicate operation. The system is an important tool for locating critical structures and navigating through the brain as precisely as possible.

Kvam removed as much of the tumor as he could, but according to John de Groot, a neuro-oncologist at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, glioblastomas usually have tendrils extending into the surrounding tissue, so the entire tumor cannot be removed. Nonetheless, the surgery was considered a success, and Herrmann recovered sufficiently to go home for Christmas 2013.

The actor faced a long treatment road after surgery. In January 2014, he started a six-week course of external beam radiation five times a week at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. His medical oncologist, Ingo K. Mellinghoff, also prescribed Temodar (temozolomide), a chemotherapy drug Herrmann took daily in pill form during the weeks he received radiation. After the initial six-week course, Herrmann continued on a maintenance dose of Temodar in an attempt to control the size of the tumor. He also took steroids, medications to control seizures and antidepressants.

“He hated the medication, particularly the steroids, and was frustrated with the way they made him feel,” says Ryen. “He gained weight and couldn’t exercise. But most of all, he was so upset that the disease had affected his brain. He would rather have had his leg amputated than his mind affected.”

Herrmann was determined not to let cancer prevent him from living his life. In March, barely four months after his diagnosis, he found out that Emma, then a senior at Northfield Mount Hermon School, a boarding school in Massachusetts, was going to Rome to sing with her choral group. Against his doctor’s advice, he went, too. “The doctors were afraid the flight would cause blood clots and did not want him to go,” remembers Emma. “But he wouldn’t take no for an answer. He and Ryen got on a plane to hear me sing. Instead of resting at home, Dad was touring the Spanish Steps. It was incredible that nothing happened during that week.”

A Rare Cancer

Each year, more than 20,000 people are diagnosed with malignant brain tumors. Of that group, about 50 percent have glioblastoma, the most virulent type, according to the American Brain Tumor Association.

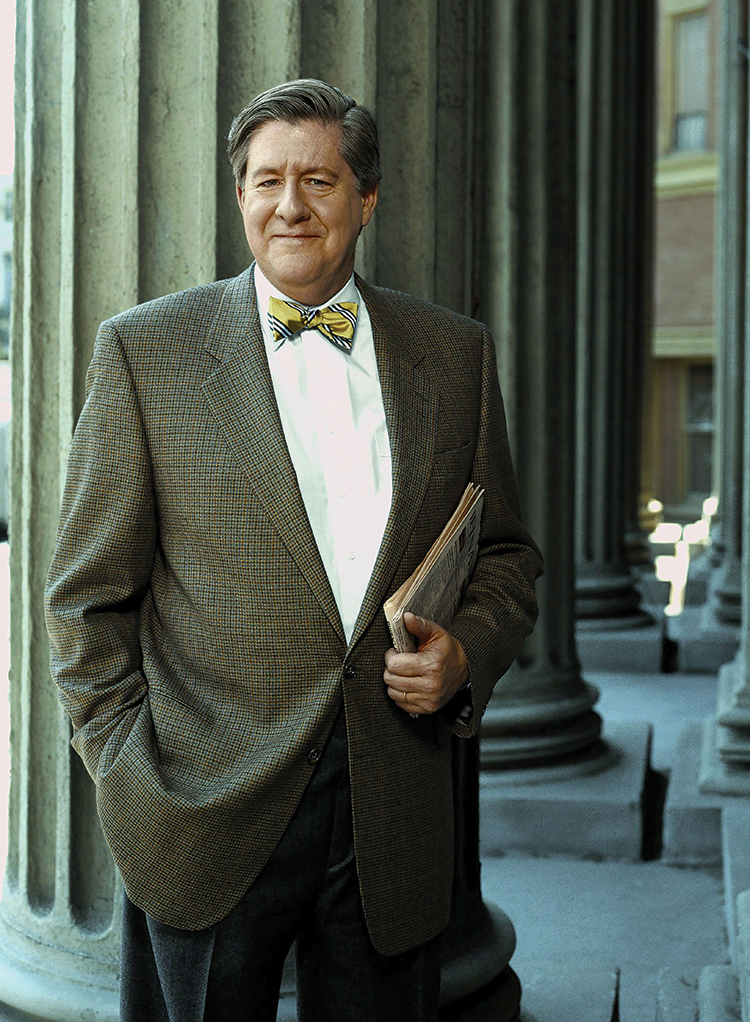

Edward Herrmann attends a media reception held in New York City in 2006. Photo © Getty Images / G. Gershoff

Traditionally, glioblastoma was classified based on “how it looked under the microscope,” de Groot explains. But growing knowledge about molecular biomarkers—mutations involving specific genes—is changing that. Increasingly, other factors, including biomarkers, are being used to further classify tumors, predict median survival time and overall prognosis, and guide the development of targeted therapies.

The first potentially therapeutic biomarker found in some glioblastomas was an elevated level of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein. Other biomarkers followed, including mutations in the gene IDH. According to Mark Gilbert, chief of the neuro-oncology branch at the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland, finding IDH proved to be a “game changer,” largely because these mutations occur in the vast majority of low-grade gliomas and a smaller number of high-grade gliomas. Furthermore, studies have shown that patients with an IDH mutation are more likely to have a better prognosis than those without one. Although no drugs that target IDH are available, research aimed at such a treatment is ongoing.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in June 2015 by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, and the Mayo Clinic has built upon earlier work by identifying a classification system based on three molecular markers. These markers are IDH, a mutation involving a gene called TERT, and a combined mutation that deletes parts of chromosomes 1 and 19. Using genetic and clinical data from 1,087 malignant glioma patients and 11,590 healthy controls, the researchers found that patients with benign or slow-growing tumors, classified as grades I or II, who tested positive for all three markers had the longest median survival time, 13.1 years, while those with only the TERT mutation had the shortest, 1.9 years. The researchers say that these findings have the potential to help clinicians identify how aggressive treatment should be. According to data from the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States on brain tumor patients treated between 1995 and 2010, only 4 percent of people between 55 and 64 years old with the same diagnosis as Herrmann live five years or longer. In comparison, 17 percent of patients in the 20-44 age group and 6 percent of those between the ages of 45 and 54 are still alive five years after diagnosis.

Building on knowledge of how immunotherapy works in treating other cancers, researchers are investigating new approaches for treating glioblastoma.

Building on knowledge of how immunotherapy works in treating other cancers, researchers are investigating new approaches for treating glioblastoma. Three therapies are monoclonal antibodies, cancer vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors.

Monoclonal Antibodies

In 2009, Avastin (bevacizumab) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for glioblastoma patients who had undergone prior therapy. A monoclonal antibody, Avastin inhibits the growth of new blood vessels that support tumors. FDA approval was based on two studies in which Avastin was effective in about 20 to 25 percent of patients, with a median response of about four months. Patients stopped taking the drug when their disease progressed or when they experienced adverse reactions.

Vaccines

A phase III clinical trial testing Rintega (rindopepimut), a vaccine that targets a mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapy (Temodar), was discontinued because it failed to improve overall survival compared with the control group. The median overall survival in the experimental group was 20.4 months compared with 21.1 months in the control group.

Checkpoint Inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitors, which unleash the immune system’s own anti-cancer responses, have been successful in treating other kinds of cancer. Two drugs used for melanoma, Opdivo (nivolumab) and Yervoy (ipilimumab), are currently being tested for recurrent glioblastoma.

To learn more about clinical trials, go to clinicaltrials.gov and search for glioblastoma.

A Glass Half Full

Even in the midst of cancer treatment, Herrmann didn’t stop working or pursuing his interests. “He always saw the glass as half full,” says Kass.

During this period, Herrmann took on the voice of FDR for Ken Burns’ documentary, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. This was followed by another Burns project—Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies—a three-part documentary based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by oncologist and cancer researcher Siddhartha Mukherjee.

When Herrmann began working on the cancer documentary, Burns, director Barak Goodman and their team didn’t know about his diagnosis, but by the end of filming in November 2014, it was hard to keep it a secret. “He had a cough, and his voice was changing,” recalls Star. “When we told them, they were very sympathetic.”

Herrmann finished the job just in time. On Dec. 4, 2014, a year after his first episode of seizures, the medication that had been controlling them stopped working. He began having seizures and was rushed to the hospital in Sharon, where the situation worsened.

Herrmann was transported to Memorial Sloan Kettering and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he was put in a medically induced coma. Multiple medications were administered in an attempt to control his seizures, but ultimately they proved to be unsuccessful. He was in the ICU for three-and-a-half weeks, with his family always close by.

Toward the end of this period, Herrmann’s seizures were still not under control, and he was fighting off multiple infections. At this point, his family faced a difficult decision. “When do you say enough?” Ryen remembers thinking. “For us, the moment came when they told us they would have to perform a tracheotomy, and Dad would no longer be able to speak. He didn’t want to live that way, so we made the decision to remove the ventilator, feeding tube and other devices that were keeping him alive.”

Herrmann lived two days after his family’s decision. He died on Dec. 31, 2014, at the age of 71.

The year had been a roller coaster, but even during the family’s worst times, there were some poignant moments.

“We were in the hospital in New York, and Dad was seizing the whole time,” recalls Ryen. “Every now and then, he would wake up, and we would talk to him. At some point, I put on Annie Lennox’s song Money Can’t Buy It, one of Dad’s favorites. He started air drumming. It was like a miracle.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.