In the fall of 2009, Jennifer Georges thought she had caught the swine flu. She had been really tired for a few days. She didn’t feel like eating, and she was running a fever. At night, she would sometimes awake drenched in sweat.

But the 21-year-old from Chicago forged ahead. She showed up at her retail job at a children’s clothing store on Monday morning and began mopping the floor. Soon after, she retreated to the bathroom, nearly passing out. “I was sweating really badly,” she recalls. Her manager, after one look at Georges’ pale face, sent her to the hospital.

Three days later, after Georges had a bone marrow biopsy, an oncologist walked into her hospital room, catching Georges partway through a turkey sandwich. The diagnosis: acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). “I had a crying fit” after he walked out, Georges says. “I had never thought about dying.”

Leukemia survivor Jennifer Georges and her mother, Margaret, sit on the steps of the family home where Jennifer, now 24, grew up. Photo by Matthew Moore

Until recent years, the prevailing image of children’s cancer had been its youngest faces—those cuddling stuffed animals rather than struggling with college admission and first jobs. But Georges, who finished college a month before her diagnosis, found herself among a group of cancer patients who remain at some risk of falling into a no man’s land, despite increasing efforts to reverse this trend. “No matter how you slice it, this population is definitely underserved,” says Peter Shaw, a pediatric oncologist who directs the adolescent and young adult oncology program at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

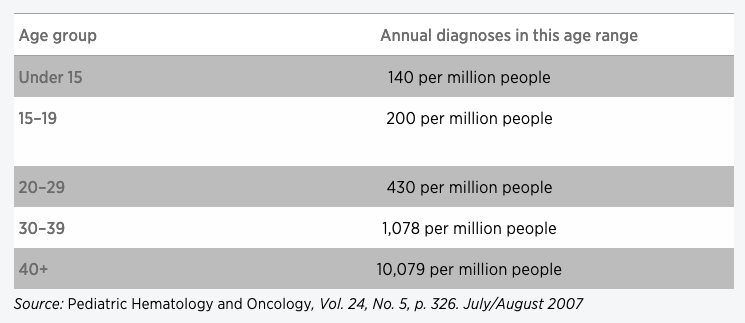

Teens and young adults, ages 15 to 24, face a higher risk of being diagnosed with cancer than children 14 and younger. Both groups currently have similar survival rates; yet there’s been a discouraging lack of progress for the young adults compared with other age groups. Five-year survival has made a steady march upward from about 60 percent to just over 80 percent among children 1 to 14 who were diagnosed between 1975 and 2004, according to an analysis of National Cancer Institute (NCI) data. But five-year survival for those 15 to 24 has hovered at or just below 81 percent since the mid-1980s.

There are many underlying reasons for the stagnant survival rate, from delayed diagnosis to inadequate treatment compliance and limited access to cutting-edge research. Most notably, perhaps, clinical trial enrollment suffers, starting with early teens, says Archie Bleyer, one of the first physicians to focus attention on teens and young adults. “It drops off like a cliff with each year of age,” says Bleyer, a pediatric oncologist at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. As many as half of children diagnosed by age 9 participate in a research study, according to Bleyer’s published analysis of NCI data from 1997 to 2005. From there, enrollment decreases stair-step fashion: 27 percent for ages 10 to 14; 14 percent for ages 15 to 19; and 5 percent for ages 20 to 24.

Given the key role that these trials can play in advancing cancer treatment, those numbers worry Karen Albritton, a Fort Worth, Texas–based oncologist and former chair of the adolescent and young adult committee at the Children’s Oncology Group, a national network of pediatric researchers. “I think the lack of young adults in clinical trials has to … be contributing to the lack of improvement in outcomes for these patients.”

Older teens and young adults are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than younger children, according to an analysis of National Cancer Institute data.

Diagnosis and Compliance

Delayed diagnosis, a frequent problem among young adults, can complicate treatment, physicians say. It can stem from teens and their support system—friends, teachers, even parents and doctors—not zeroing in on worrisome symptoms. Add to that mix a hefty dose of adolescent invincibility and denial. Tanya Tekautz, a pediatric oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic, treated one teenager whose testicular tumor grew so large that it altered how he walked. Bleyer describes a teen girl who hid a basketball-sized bone malignancy on her leg beneath long skirts.

Various age-related factors also can influence adolescents’ and teens’ treatment, including their access to research studies. Bleyer ticks off a long list: self-image, invulnerability, romantic relationships, family dynamics, insurance coverage, school and employment challenges, substance abuse and drinking. Because studies require strict adherence to treatment protocols, physicians can be more reluctant to enroll teens and 20-somethings, he says.

Teens will sometimes confess to missing doses of oral chemotherapy and other pills, Shaw notes. “And they probably are underestimating how much they miss.” Georges, who was referred to a hospital affiliated with the University of Chicago Medical Center and soon enrolled in a leukemia trial for adolescents and young adults, sheepishly acknowledges that she occasionally forgot a dose. (To help stay on track, she used a pill pack marked with “a.m.” and “p.m.”) If she missed an evening pill, she would take it upon waking and then push back other doses to later that day.

Photo by Matthew Moore

Uncertainties about treatment compliance also can muddy insights from the limited data that’s already available, says Wendy Stock, a University of Chicago leukemia specialist.

Stock has authored one of several recent studies involving ALL that have shown improved survival when adolescents and young adults receive a pediatric treatment approach rather than an adult regimen. According to her study’s findings, published in 2008 in the journal Blood, 63 percent of those ages 16 to 20 on the pediatric regimen had no evidence of disease at seven years, compared with 34 percent who received the adult regimen. A closer look at specific ages revealed an intriguing discrepancy, Stock says. Teens ages 16 and 17 had similar results with both regimens. But for those ages 18 to 20, the pediatric regimen was superior: 57 percent had no evidence of disease, compared with 29 percent on the adult protocol.

The number of patients involved—321—is relatively small, Stock cautions. But she wonders if the older teens on the adult protocol might have been more likely to be living independently than the 18- to 20-year-olds getting treatment through pediatric hospitals, and thus they missed out on some of the family support that is often vital to sticking with a complex treatment regimen.

In a multicenter NCI study that Stock is now leading—the same study that Georges joined—adult oncologists are using a pediatric regimen to see if they can achieve similar survival results as the pediatric oncologists. The study, which is no longer enrolling participants, includes patients 16 to 39. “If we improve survival by 15 to 20 percentage points, then that would be incredible,” Stock says.

Resources can help teens and young adults with cancer evaluate their options.

Don’t be reluctant to ask if an older teen or even a 20-something could benefit from care at a nearby pediatric hospital, physicians say. Also, find out if any potentially beneficial research trials exist and are enrolling participants, says Nita Seibel, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) researcher who is focused on improving adolescent and young adult treatment. A few resources to check out:

- The National Institutes of Health provides a searchable database of clinical trials. Type in the individual’s diagnosis and other key words to locate relevant studies.

- The NCI’s PDQ (Physician Data Query) database includes detailed treatment summaries, broken down into adult and pediatric. Seibel suggests reading information from both age groups to see if there’s any difference in approach.

Bridging the Gap

Nationally, some steps have been taken to broaden clinical trial enrollment. In the last decade, the Children’s Oncology Group has raised the maximum age for some pediatric research studies—traditionally 18 or 21—to as high as 30 for ALL and 50 for sarcomas, Albritton says. To be eligible, though, participants have to get care through a children’s facility, she says. “Then you go, ‘Is it really appropriate for a 22-year-old to be treated at a pediatric hospital?’”

Online Resources for Young Adults

The Ulman Cancer Fund for Young Adults

In fact, there’s no consensus about where patients in this age group should be treated. Georges ended up at an adult medical center; many others her age go to pediatric facilities. According to Bleyer, picking the best site probably depends not just on the patient’s age and personal preference, but on his or her cancer diagnosis. He recently authored a study, published in 2009, which found that 15- to 19-year-olds diagnosed with a cancer more common in children, such as leukemia, had improved survival at a children’s hospital versus an adult facility. In contrast, the results were better at an adult hospital for several cancers more common in adults, including a variety of carcinomas and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

In another strategy to bridge the young adult gap and expand clinical trial enrollment, officials at the NCI have been developing a system—through its Cancer Trials Support Unit—for adult cancer physicians to enroll patients in pediatric studies and vice versa. The first such study, which began in December 2010, gives adult oncologists access to pediatric trials for Ewing sarcoma patients up to age 50.

All these steps are good, but remain somewhat incremental, says Albritton, sounding a bit discouraged. “I think it’s going to take so many avenues to change—there are just so many issues and barriers,” she says. Bleyer, on the other hand, is optimistic, citing increasing evidence of heightened awareness of adolescent and young adult cancers. “I’m expecting, within the next decade, improved survival and quality of survival during and after treatment,” he says.

If that’s the case, more young adults may have the chance to experience post-treatment lives like Georges’. By the spring of 2011, Georges was in remission and her hair, once curly, started growing back straight. She began dating, quick to weed out prospects based on whether the personal chemistry was sufficiently promising to share her cancer status; since last summer, she’s had a steady boyfriend. She also continued to study, with an eye on the future, taking classes online and obtaining her master’s in business administration in October 2011. And in January 2012, she finished her leukemia treatment.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.