Metformin, an inexpensive drug that’s widely prescribed to treat type 2 diabetes, is showing promise as a potential cancer therapy, too. Recently published studies, mostly on mice and on cancer cells in the lab, suggest that the drug may slow or stop the growth of tumor cells in cancers of the skin, mouth, liver, pancreas and prostate. Earlier studies indicated that the drug could be effective in treating breast and colon cancers, as well.

Metformin “offers the potential for a drug that can target cancer in a relatively safe manner and won’t cost as much as other targeted therapies coming down the line,” says Geoffrey Girnun, a cancer biologist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Girnun led a recent study, published in the April 2012 issue of Cancer Prevention Research, which suggested that metformin prevented the growth of liver tumors in mice. “Diabetics take metformin chronically, and by and large they have low incidence of side effects,” he says. Generic versions of the drug are as cheap as $1 per day, with some pharmacies giving it away for free.

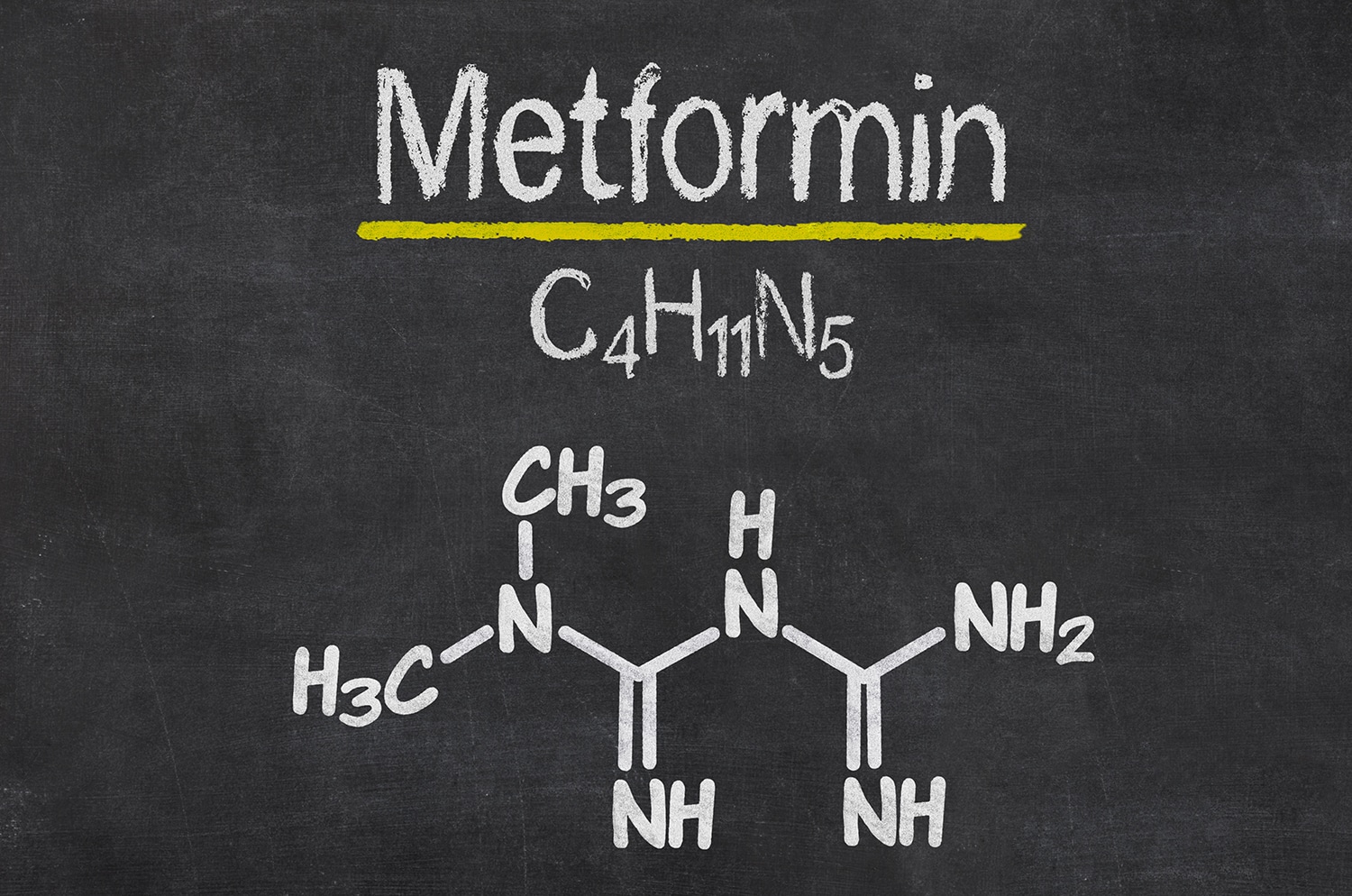

The mechanism behind metformin’s anticancer activity isn’t clear. But the drug reduces blood concentrations of insulin—which is known to fuel some cancers—by activating an enzyme that helps muscles absorb glucose. That enzyme is also suspected of stimulating a protein that inhibits proliferation of malignant cells. Interest in metformin increased after a large study on the health of diabetics, published in 2005 in the British Medical Journal, suggested that the drug may reduce cancer risk. In a follow-up observational study, published in 2009 in Diabetes Care, the same researchers reported that among about 8,000 diabetics, cancer was diagnosed in 7.3 percent of metformin users compared with 11.6 percent of non-metformin users.

Some of the most encouraging results have come primarily from cell and mouse studies—but more clinical trials are needed to determine whether humans exhibit similar effects from the drug. One ongoing trial, an international phase III study led by the National Cancer Institute of Canada, is examining metformin’s effects on early stage breast cancer. Ingrid Mayer, an oncologist at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tenn., is an investigator on that study.

“In mouse models, metformin seems helpful for all kinds of breast cancers,” says Mayer. The drug even seems to decrease the growth of tumor cells and increase cell-death in “triple-negative” breast cancers, which are notoriously difficult to treat: “That subset of patients could benefit the most.”

Researchers like Mayer are looking forward to seeing how the drug works in people, to understand if and how it might fit into a treatment regimen.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.