ANDREW SCHORR was 61 years old and had already been living with chronic lymphocytic leukemia for 15 years when he was diagnosed with myelofibrosis, a rare blood cancer, in 2011. He was prescribed the oral targeted therapy Jakafi (ruxolitinib), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration the same year. His private health insurance paid the entire cost.

After Schorr turned 65 and went on Medicare, he learned that Jakafi would now cost him $10,253 annually. In January 2020, Schorr switched to another oral targeted drug, Inrebic (fedratinib), and the cost climbed higher. This year, he expects he will pay $13,080 for the drug out of his own pocket.

Andrew Schorr expects to pay more than $13,000 this year for an oral drug to treat his myelofibrosis. Photo courtesy of Patient Power

“Going to Medicare for me, related to my oral drug cost, was painful, and it’s gotten more painful,” says Schorr, who lives in Carlsbad, California, and is a journalist and co-founder of the cancer patient education and advocacy organization Patient Power.

For most Americans older than 65 and some younger people with disabilities who qualify, Medicare is a vital government program. Older adults with cancer are less likely to report medical financial hardship overall than young adults with the disease, some research shows.

Still, people with cancer who are covered by Medicare can run into financial trouble, says health policy researcher Juliette Cubanski, who is deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation in San Francisco. “Medicare is great, but there are gaps,” she says.

Mind the Medigap

When signing up for Medicare, explains lawyer Monica Bryant, people first need to choose between Original Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Bryant is chief operating officer of the national nonprofit organization Triage Cancer, which offers education on legal and practical matters related to cancer.

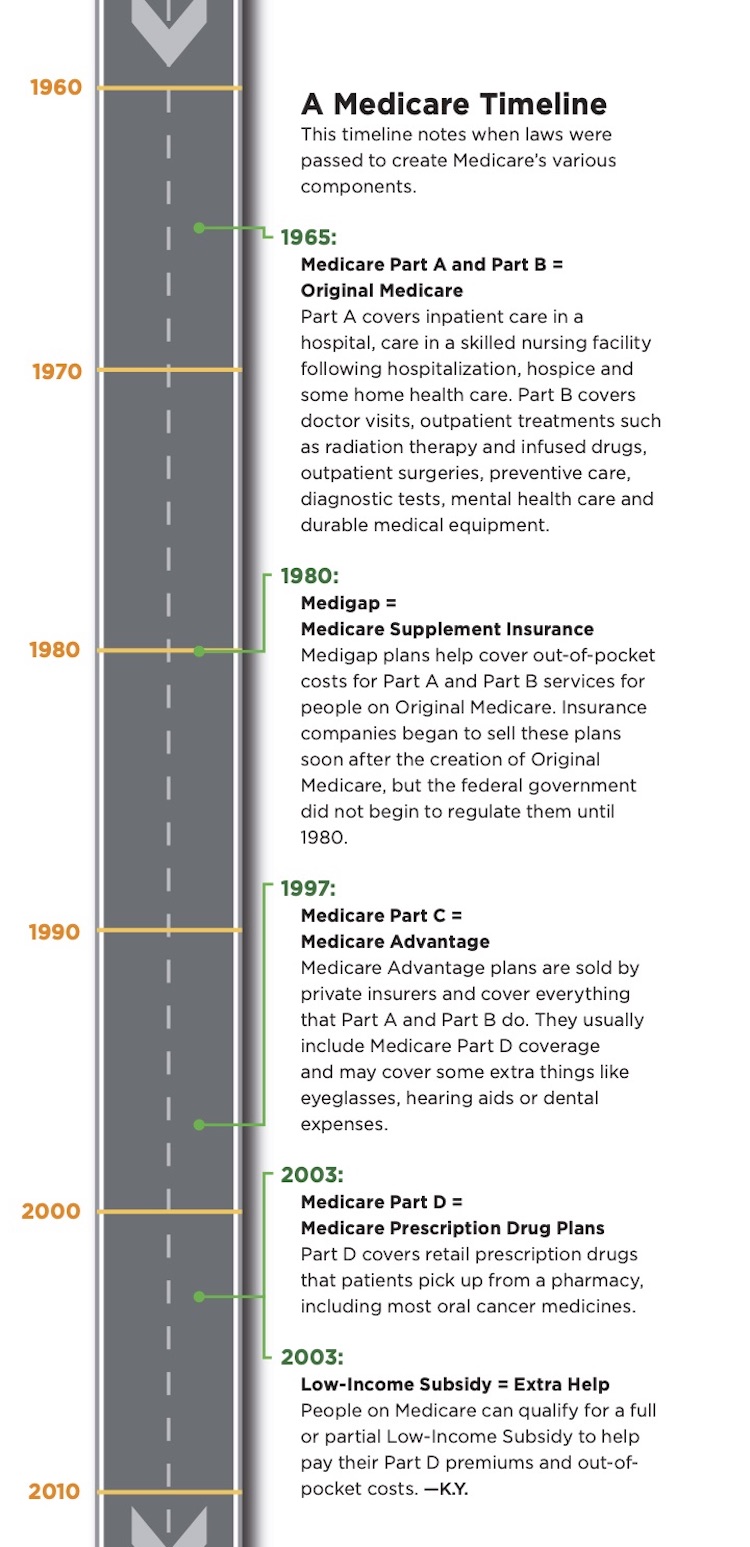

Original Medicare is made up of Medicare Parts A and B, which were the only components of the program when it was created in 1965. Part A is provided at no cost to most Americans and primarily covers inpatient hospital services. People can also pay a monthly premium to enroll in Part B, which covers outpatient care such as doctor visits and treatments like radiation therapy and infused drugs.

People on Original Medicare can also enroll in and pay for a stand-alone Medicare Part D plan. These plans cover prescription drugs dispensed directly to patients via their pharmacies.

Finally, if they are not eligible for Medicaid or some other supplemental coverage, Bryant says, people choosing Original Medicare might want to pay for Medicare Supplement Insurance, otherwise known as Medigap, to help cover out-of-pocket costs from Part A and Part B services. Without a supplemental plan, people enrolled in Medicare Part A are responsible for a deductible of $1,408 when they are admitted to the hospital. They can pay this amount multiple times in one year if they have several hospital stays that are more than 60 days apart. They can also face mounting daily costs if they are hospitalized for more than 60 days.

Patients must also pay 20% coinsurance for all Part B services after meeting a deductible, and there is no out-of-pocket maximum. “That can be a huge financial burden for people who don’t have those other supplemental plans that help protect them from out-of-pocket spending,” says Stacie Dusetzina, a health policy researcher at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Watch this video to get tips on how to navigate Medicare as a cancer patient from Cancer Today‘s digital editor Kate Yandell and Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Nearly one in five people with Original Medicare lack supplemental coverage, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. A study published in 2017 in JAMA Oncology found that among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer who were surveyed between 2002 and 2012, patients without supplemental insurance paid a mean of $8,115 out of pocket for their medical care each year, with these expenses consuming about 24% of their household income. Patients with supplemental insurance via Medigap paid an average of $5,670 out of pocket each year, or 14% of their income.

Bryant says that people may go without supplemental insurance because they are not aware Medigap plans exist, or they may find signing up for one too difficult. For instance, Medicare has Parts A through D, while supplemental plans are lettered A through N. These parallel but unrelated lettering schemes can cause confusion, Bryant says. People may also feel they cannot afford a Medigap plan or may not appreciate its value. However, Bryant emphasizes that not paying for supplemental insurance can be much more expensive in the long run than paying for it when people are diagnosed with cancer.

If a person does not enroll in a Medigap plan during their initial enrollment period for Medicare, they may find themselves locked out of getting a Medigap plan in the future, Bryant warns. Insurers are permitted later to deny insurance, delay coverage or raise premiums based on pre-existing health conditions. Additionally, companies are not required in all states to offer Medigap plans to people under 65 who get Medicare due to being on disability.

Medicare Advantage, also known as Medicare Part C, provides an alternative to Original Medicare, Bryant says. Medicare Advantage plans cover the services offered by Parts A and B, and may offer extra coverage. Those who choose Medicare Advantage may need to pay an additional premium as well as their Part B premium. Part D coverage is usually bundled into Medicare Advantage plans.

People with Medicare Advantage cannot enroll in Medigap plans. Instead, there is an out-of-pocket maximum for Part A and Part B services offered via Medicare Advantage, Bryant explains. Patients with Medicare Advantage can only see doctors and get care at hospitals that are in their plan’s network, however, while those on Original Medicare can access a broader group of providers.

Finally, once a person chooses a Medicare Advantage plan, they may struggle to purchase a Medigap plan if they decide they want to go back to Original Medicare. “Because of these rules, people get locked into their choices and don’t have an easy ability to switch,” says Cubanski. “That can tie people’s hands.”

The Part D Dilemma

Regardless of whether someone chooses Original Medicare or Medicare Advantage, they will face the risk of high costs for oral medications, even if they elect to receive Part D.

When Part D was created in 2003, it represented a step forward, since coverage for outpatient oral drugs had previously been largely unavailable to Medicare beneficiaries, recalls Adam Olszewski, a hematologist and health services researcher at Lifespan Cancer Institute and Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. However, “the system was completely unprepared for what happened soon after, which was the arrival of a large number of extremely expensive oral anti-cancer medications,” he says.

The number of anti-cancer drugs covered by Medicare Part D increased from 13 in 2010 to 54 by 2018, according to a paper co-authored by Dusetzina and published May 28, 2019, in JAMA. Based on calculating the out-of-pocket costs of the 13 drugs available in 2010, patients who took one of these drugs could expect to spend an average of $10,470 out of pocket annually by 2019.

In 2020, patients pay full costs of drugs via Part D until they reach their annual deductible, which is a maximum of $435. Next, patients must pay 25% to 33% of the price of their specialty drugs—defined as drugs costing more than $670 per month—in the initial coverage phase. Then begins the coverage gap phase, in which the patient pays 25% of drug costs. Finally, the patient enters the catastrophic coverage phase and pays 5% of the drug costs each month.

The majority of costs are now incurred during the catastrophic coverage phase, Cubanski says. Schorr, for example, paid $2,300 out of pocket for Inrebic in January before entering the catastrophic phase of coverage by February. He now pays $980 per month.

“Cancer really unfortunately is kind of the perfect example of how the benefit falls short in providing financial protection that people really need in order to continue to take the medications that they need,” Cubanski says.

Bob Preddy and his wife, Martha Armstrong, were surprised by the cost of his oral drug for multiple myeloma. Photo courtesy of Bob Preddy and Martha Armstrong

The cost of oral drugs on Medicare came as a shock to Bob Preddy and Martha Armstrong. The couple moved from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Wilmington, North Carolina, in January 2014 with a plan to retire soon after. Instead, Preddy, who was on Original Medicare with Part D and a Medigap plan, was diagnosed with multiple myeloma two months later, at age 67. After a transplant with his own stem cells in October 2014, Preddy was prescribed the oral cancer drug Revlimid (lenalidomide). Preddy and Armstrong soon found themselves paying more than $13,000 per year on average for the drug. It was only in 2019, after Preddy was able to stop taking Revlimid, that he retired with a plan to travel more, although the coronavirus has halted these plans.

Preddy spoke in an interview with Cancer Today in 2018 about the emotional impact of this expense, which he was told would last for an indefinite number of years. “There’s a certain amount of guilt sometimes you feel because you, meaning the cancer patient, have to pay these extraordinary costs for your medication,” he said. “It’s affecting not just you, it’s affecting the life of your spouse, and if you’ve got a family, the whole family. I know Martha says you can’t think like that, but you know what? You can’t help it.”

Finding Ways to Pay

For many patients, the large payment needed to start an oral drug is a major barrier, Olszewski says. Fortunately, he says, resources exist to help people pay for drugs.

Unlike people on private insurance, people on Medicare cannot receive assistance from drug companies to pay for their drugs. The federal government considers direct assistance from pharmaceutical companies a kickback if a patient is also trying to get help paying for the drug from their Part D insurance, Cubanski explains. However, Medicare patients can accept assistance from charitable organizations.

Medicare.gov has information on Medicare and how to enroll and also provides a guide to Medicare for cancer patients.

State Health Insurance Assistance Programs, or SHIPs, are state programs that provide counseling to people about Medicare.

Triage Cancer has a Quick Guide to Medicareand recent held a webinar on Medicare and cancer.

The Kaiser Family Foundation offers an overview of Medicare and other information on the program.

These organizations have varying rules to determine eligibility. Many funds support patients who make under five times the federal poverty level. In 2020, this means that individuals who make under $63,800 per year may qualify for assistance.

“If you’re approved, you’ll get some funds that you can then use for copay support. Those dollars are coming largely from pharmaceutical manufacturers,” which make donations to the charitable organizations, Dusetzina says. While a drugmaker is not permitted to earmark donated funds to pay for a specific drug, they are permitted to donate money to support patients with a given disease, she explains.

Applying for patient assistance programs can be daunting, Olszewski says. His cancer center has hired patient navigators to help patients through the process. Olszewski says that nearly half of his cancer center’s patients 65 and older get charitable assistance in paying for their oral cancer drugs and that navigating the assistance system may delay starting treatment.

In contrast, Olszewski says he is relieved when he learns a patient qualifies for Medicare’s Low-Income Subsidy program, also referred to as Extra Help. People qualify for a full subsidy if they qualify for Medicaid or certain other government programs or make 135% or less of the federal poverty level—which for individuals in most of the U.S. means they must make under $17,226—and have limited assets. These people will pay $8.95 at most to pick up prescriptions and don’t have to pay Part D premiums. For these low-income patients, “I know that treatment can start faster,” Olszewski says.

People making under 150% of the poverty level and with slightly more assets can qualify for a partial Low-Income Subsidy, but these patients can still face thousands of dollars in costs. “Because that’s a very low-income group, they might actually be worse off than even the people who don’t get any subsidies at all,” says Dusetzina.

Olszewski says that occasionally, patients are so taken aback by the high price of the drugs that they decide not to undergo that treatment. “Some older patients have a very strong sense of societal responsibility, and they have feelings about what they deserve and what they do not deserve,” he says.

On Dec. 12, 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would cap out-of-pocket spending on retail prescription drugs covered under Medicare Part D at $2,000. The bill remains in the Senate. A proposed Senate bill suggests that out-of-pocket spending for drugs covered under Medicare Part D be capped at $3,100 per year. Despite bipartisan support for the idea, the coronavirus pandemic appears to have diverted attention from passing legislation capping Part D spending, Cubanski says.

Practical Impacts

High costs can lead patients on Medicare to forgo treatments. One 2018 paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found a little more than 42% of patients with Medicare Part D drug plans abandoned prescriptions for oral cancer drugs that cost more than $2,000 for a fill, meaning that they did not fill an approved prescription and still had not purchased the drug 90 days later.

Research by Dusetzina and others indicates that cancer patients who qualify for Medicare’s full Low-Income Subsidy program are significantly more likely to start treatment with an oral anti-cancer drug, and to start sooner, than patients who make more money and don’t qualify for this support. The pattern was found in those with metastatic kidney cancer and non-small cell lung cancer, for instance.

People who do not have prescription drug coverage at all are another vulnerable group. In a 2018 paper published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Olszewski, Dusetzina and their colleagues found that multiple myeloma patients on Medicare without prescription drug coverage were more likely to receive classic chemotherapy or go without active cancer treatment entirely than patients with Part D coverage, possibly due to being unable to afford oral drugs like Revlimid. These patients without prescription drug coverage had a lower chance of survival three years later than patients with prescription drug coverage.

Even when patients do manage to find the money to pay for their care, high medical payments can cause stress, says Olszewski. “It’s not very realistic to expect patients to spend all their savings on these medical bills, including prescriptions,” he says. “I don’t think as a nation that we are doing a really good job trying to understand that older patients need more medical care. They should not be forced to work throughout their lifetime to spend it in the last few years of life on medical bills.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.