FOR CLOSE TO 50 YEARS, Charles M. Schulz sketched life’s challenges through the characters he created in his world-renowned comic strip Peanuts. In that time, Snoopy, Charlie Brown, Linus and Lucy jumped from a man’s imagination and newsprint into mainstream culture.

“He philosophized like Linus, was sensitive to music like Schroeder, could be peevish at times like Lucy, and was imaginative like Snoopy,” says Rheta Grimsley Johnson, author of the authorized biography Good Grief: The Story of Charles M. Schulz. “But most of all, he was like Charlie Brown.”

Like the protagonist in his strip, Schulz was quiet and unassuming, Johnson says. He also carried each of his failures with him. “He had this ability to make you feel sad for him,” says Johnson, “but also … the ability to nurse these little slights and grudges from high school. These all play out in the strip in the loser Charlie Brown.”

Always Drawing

Charles Monroe Schulz, an only child, was born in 1922 in Minneapolis to Carl Fredrich August Schulz, a barber, and Dena Bertina Halverson Schulz, a full-time homemaker. His uncle gave Schulz the nickname Sparky, after the character Spark Plug, a racehorse in the Barney Google comic strip by Billy DeBeck. The nickname stayed with him throughout his life.

Schulz, who spent most of his childhood in St. Paul, Minn., was a socially awkward, shy child. His kindergarten teacher predicted that he would one day become an artist, according to Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography by David Michaelis. Ten years later, Schulz, at age 15, published an illustration of a dog in the syndicated comic strip Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

In 1940, as Schulz was finishing his senior year of high school, his parents enrolled him in art correspondence classes at Federal School of Applied Cartooning in Minneapolis. Schulz later admitted that he took classes by mail because he feared sitting in a class next to artists who might draw better than him.

World War II interrupted Schulz’s art education. He started basic training in 1943—just two weeks after his mother died of cervical cancer—and served as a machine-gun squad leader in Germany, France and Austria during the final months of the war in 1945. After he was discharged from the service in early 1946, Schulz returned to St. Paul and his father’s apartment, where he worked on his craft.

A few months later, Schulz started working at his alma mater, which by then had changed its name to Art Instruction Schools. At the time, he was motivated by a powerful desire: He was determined to see his illustrations published.

Pushing the Strip

Schulz started pitching his comics, which first appeared in single-panel format, to local newspapers. In 1947, the comic, called Li’l Folks, appeared in the Minneapolis Tribune, and then the St. Paul Pioneer Press once a week. From 1948 to 1950, the Saturday Evening Post published 17 of his panels.

In June 1950, Schulz landed a five-year contract with United Feature Syndicate, which named his strip Peanuts. Schulz despised the name because he thought it had nothing to do with the comic. Four months later, the first syndicated Peanuts comic strip, now in four-panel format, appeared in newspapers in seven cities throughout the country.

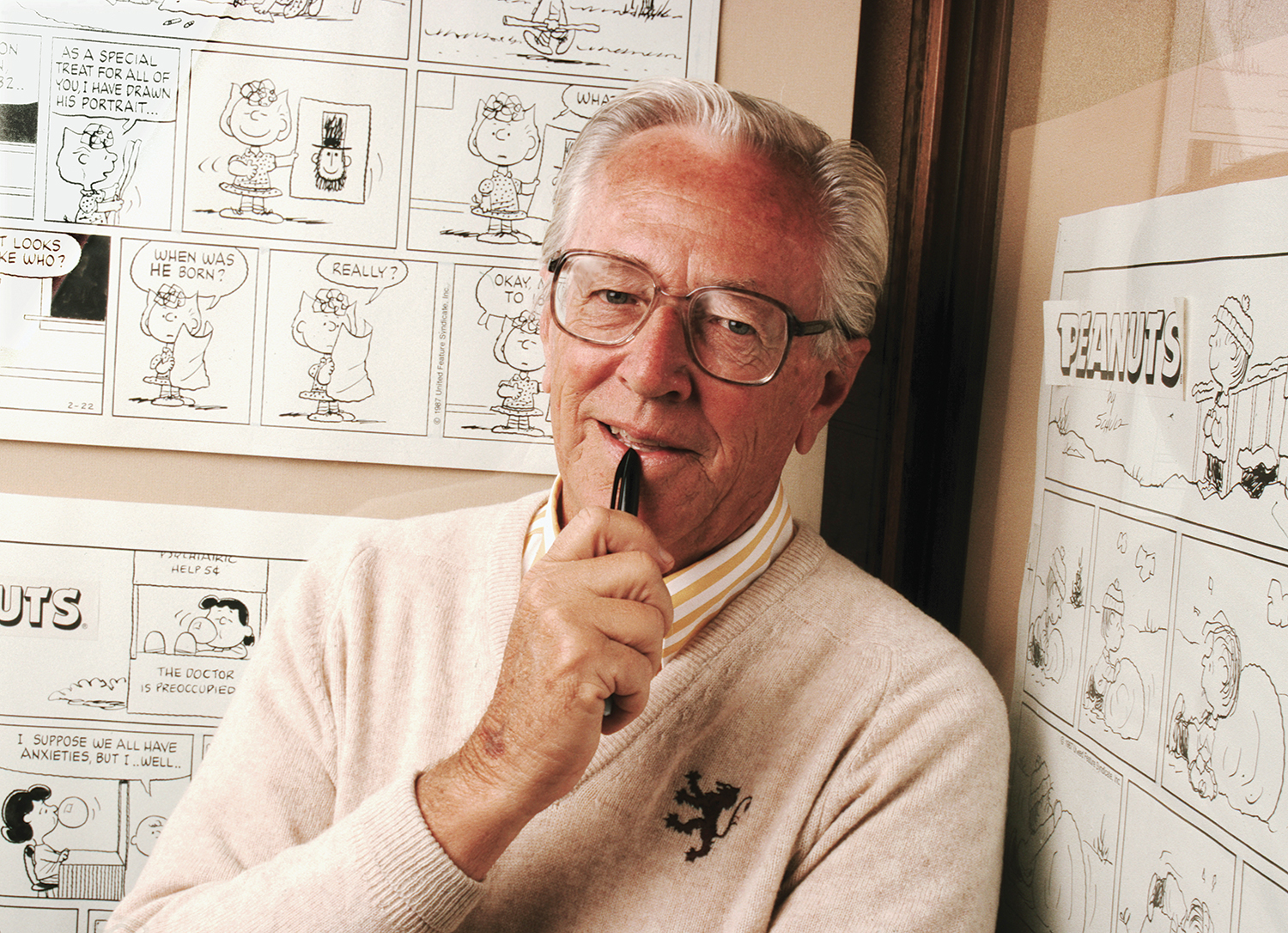

Charles Schulz insisted on creating all aspects of his comic strip, including lettering, which was a task often relegated to other artists once a cartoonist had become successful. Photo © AP / Corbis

A Personal Sketch

Just as Peanuts was starting to appear in newspapers across the country, Schulz, 28, married 22-year-old Joyce Halverson, a divorcee with a young daughter. Schulz adopted Joyce’s daughter, and the couple had four more children. After living in Colorado Springs, Colo., and Minneapolis, the family moved to Sebastopol, Calif., in 1958.

Schulz and Joyce divorced in 1973, after being legally separated for nearly a year. Joyce remarried the day after the divorce was final, according to the biography Schulz and Peanuts. The following month, Schulz, then 50, married Jean Forsyth Clyde, who was almost 17 years his junior and who had two children of her own.

In his professional life, Schulz was a perfectionist. His wife Jean says that he insisted on drawing every strip, without hiring assistants for lettering, as many of his colleagues did. “ ‘If you don’t do it yourself, you don’t get the aesthetic,’ ” she recalls her husband saying. “He wanted his work to be the very best he could do that day.”

Over Schulz’s career, original Peanuts comics failed to appear for only five weeks—when the cartoonist took time off for his 75th birthday. He even banked three months of panels before undergoing quadruple bypass surgery in 1981.

Charles Schulz lets his dog, Sparky, taste his soft drink. The photograph was taken sometime between 1940 and 1945. Photo courtesy of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Santa Rosa, Calif.

Health Concerns

In 1999, at age 76, Schulz was still at his drawing board. But during the summer, he began feeling drained, Jean recalls. His doctor suspected some type of cancer, says Jean, and recommended diagnostic tests.

While at work shortly after seeing his doctor, Schulz felt painful cramps and lost sensation in his lower body. Surgeons performed emergency surgery to remove a life-threatening blockage in his abdominal aorta. During or just after the abdominal aorta surgery, a blood clot traveled to Schulz’s brain, causing a stroke, which led to additional complications.

While removing the blockage, the surgeons discovered that Schulz had colon cancer. They removed as much of the cancer as they could, but it had already metastasized.

After undergoing a few months of chemotherapy, Schulz died on Feb. 12, 2000. His final original Sunday comic strip appeared the following day.

Treatment Advances

Since Schulz’s death 14 years ago, a combination of drugs and surgical advances has helped to extend aver-age survival times for people with metastatic colorectal cancer from about 12 months then to 32 months now, says Johanna Bendell, an oncologist and clinical researcher who studies gastrointestinal cancer at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

Jean Schulz doesn’t recall her husband’s chemotherapy regimen, but the standard therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer at the time of his diagnosis included surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible and a regimen that comprises 5-FU (5-fluorouracil) and leucovorin, commonly referred to as 5-FU/LV.

In the late 1990s, researchers began exploring whether adding drugs to this combination could improve survival for patients. In 1996, Camptosar (irinotecan), which has been shown to extend survival by two months when added to 5-FU/LV, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And in 2002, the FDA approved the use of Eloxatin (oxaliplatin) along with 5-FU/LV for metastatic colorectal cancer that had progressed or recurred. In 2004, the FDA approved the combination as a first-line treatment after studies showed this combination increased survival by an average of five months.

Patients also have an option of choosing an oral chemotherapy drug, called Xeloda (capecitabine), which is converted into 5-FU in cancer cells. This oral drug provides convenience to patients and has worked as well as 5-FU/LV in studies. However, Xeloda comes with some more pronounced side effects and has been expensive for some patients, according to Bendell.

Some patients with metastatic colorectal cancer have also benefited from a new class of drugs, known as angiogenesis inhibitors, which interfere with the growth of the tumor’s new blood vessels. The FDA approved the first angiogenesis inhibitor Avastin (bevacizumab) for metastatic colorectal cancer patients in 2004 after studies showed the addition of Avastin to 5-FU/LV and Camptosar extended the lives of patients on average by about five months compared with patients who used 5-FU/LV and Camptosar alone. (Avastin can also be combined with 5-FU/LV and Eloxatin.)

In the past two years, the angiogenesis inhibitors Zaltrap (ziv-aflibercept) and Stivarga (regorafenib) have also been approved for treating metastatic colorectal cancer to give patients more options.

Using combinations of some of these newer treatments before surgery—called neoadjuvant therapy—can shrink the tumor and may make surgery possible for some patients whose tumors have spread to the liver, where colon cancer often metastasizes.

A key focus now is determining which patients are likely to benefit from a particular treatment. Genetic testing has helped in some cases. For example, most patients with metastatic colorectal cancer have their tumor tested to see if it has a KRAS mutation, as tumors with this mutation will not respond to Erbitux (cetuximab) or Vectibix (panitumumab), two drugs that work by inhibiting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

However, some tumors with normal KRAS genes do not respond to EGFR inhibitors either, and scientists are still exploring which genetic markers might help predict success for these patients.

“Patients [whose tumors have] a normal KRAS gene at least have a chance that the EGFR inhibitors might work,” says Bendell. “We are learning more every day about what treatments work for each patient. We still have a way to go.”

These screening measures can help detect colorectal cancer.

For colorectal cancer to be detected when it’s most curable, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends the following screening methods for people between the ages of 50 and 75 with no other risk factors.

High-sensitivity fecal occult blood test. This test checks the stool for blood, which may be a sign of polyps or cancer. Patients can provide stool samples at home, after they receive a kit from their health care provider. Those with a positive test will be referred for a colonoscopy. The USPSTF recommends these tests be done annually, starting at age 50.

Sigmoidoscopy. A sigmoidoscope, a thin tube with a light on the end, uses a tiny video camera to transmit images of the rectum and lower colon (called the sigmoid colon) to help detect polyps or cancer. Physicians can insert special instruments into the scope to biopsy and remove polyps. Typically, if polyps are found, the patient will require a colonoscopy for a more thorough analysis of the entire colon. The procedure, recommended every five years for individuals between 50 and 75, doesn’t typically require sedation. Patients need to give themselves an enema before the procedure to cleanse the lower colon.

Colonoscopy. A colonoscope, a tube that is longer than a sigmoidoscope, allows physicians to view the entire colon. The night before a colonoscopy, patients must take laxative agents to completely cleanse the colon. The patient is usually sedated during the procedure. If polyps are found, they may be removed by passing a wire loop through the colonoscope to cut the polyp from the wall of the colon using an electric current. Testing is recommended every 10 years. More frequent screening may be required if the patient has a history of developing polyps.

People who have a family history of premalignant lesions (known as adenomatous polyps) or colorectal cancer before the age of 60 or who have a family or personal history of inflammatory bowel disease require more frequent screening. Talk with your doctor about your individual risk.

Sources: The American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute

An Emphasis on Preventive Screening

Schulz’s chance of longer-term survival also might have improved had he been diagnosed earlier, but colorectal cancer screening was just beginning to be widely promoted when Schulz learned he had colon cancer in 1999. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) started recommending routine colorectal cancer screening in 1996, just three years before Schulz was diagnosed with the disease.

Today, the USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer with fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy for people between ages 50 and 75 who are at average risk. Over the past three decades, the number of adults being screened for colorectal cancer has risen substantially. In 1987, about 35 percent of adults in the recommended age range underwent screening in the U.S.; by 2008, 63 percent of people got recommended screening.

Studies indicate that screening can help decrease the incidence of and deaths from colorectal cancer. Since the mid-1980s, the incidence of colorectal cancer has been declining, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). Colorectal cancer, however, is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. The ACS estimated approximately 143,000 Americans would be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2013 and more than 50,000 would die from the disease.

Educational campaigns for colorectal cancer screening could help lower the number of colorectal cancer deaths, as Schulz’s son, Monte Schulz, intimated in a televised public service announcement for the National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance a year after his father died: “He didn’t choose to quit drawing Peanuts. Colon cancer stole it away from him, then took his life. … I miss my father. Get tested. Please don’t forget.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.