WHEN FRANK GARDEA was diagnosed with liver cancer in March 2013, he never expected he’d live to ring in 2014—let alone see the calendar turn to 2018. Neither did his doctors.

That March day, the 59-year-old resident of Woodland Hills, California, showed up at a Los Angeles County emergency room with severe abdominal pain. The pain itself wasn’t new; he’d been talking to doctors about it for two years. But the intensity was. Soon, the ER team discovered what Gardea’s other doctors had not seen: an 8-centimeter tumor on his liver.

Tests showed Gardea had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer in adults. He also had hepatitis C and early stages of cirrhosis. Gardea says his doctors told him that the tumor’s size and the underlying liver disease left him with a poor prognosis, and they advised him to get his affairs in order. Gardea felt certain he had only a few more months to live, but then, by chance, other doctors doing rounds saw his chart. They advised him to seek treatment as quickly as possible at the Pfleger Liver Institute of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

That May, he had his first appointment with medical oncologist Richard Finn at UCLA. Finn ran tests and scans and said he’d see him in two weeks. But within days, Gardea was back in an emergency room—this time the one at UCLA.

Gardea’s tumor, which by then had grown to 14 centimeters, had burst. The liver specialists at UCLA immediately performed a transarterial chemoembolization, a procedure designed to shrink the tumor with chemotherapy and block the blood vessels inside the liver that lead to the tumor. A few weeks later, Finn started Gardea on Nexavar (sorafenib), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor; it works by suppressing the signals that tell cancer cells to grow and by keeping the cancer cells from building the new blood vessels they need to grow.

The treatment wasn’t smooth sailing. While Gardea was on Nexavar, he developed an unrelated deep vein thrombosis—a blood clot in his leg—which put him back in the hospital. He collapsed and broke his ankle. But the Nexavar was working. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is used as a biomarker for liver cancer. At the time of Gardea’s chemoembolization, his AFP level was 94,000. For the past three years, it’s been in the normal range (0-10).

Very few patients with a tumor as large as Gardea’s and a liver as damaged as his have seen this type of treatment success. Gardea’s response to the Nexavar is “remarkable,” Finn says. “I’ve had maybe three or four patients over the course of my career like him.”

An Increasing Concern

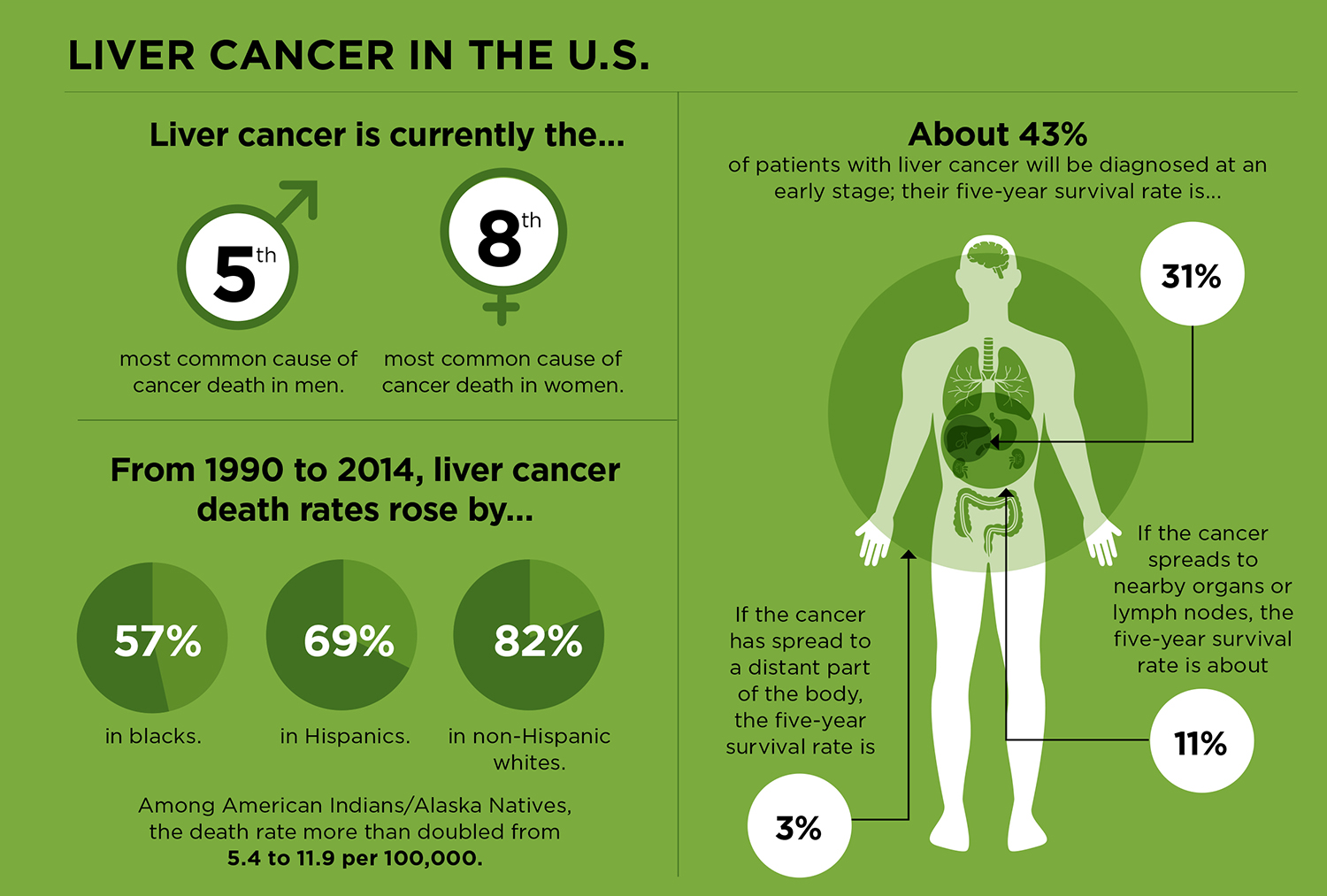

The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be about 42,220 people diagnosed with liver cancer in the U.S. in 2018 and about 30,200 deaths from the disease. (It is expected to be the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in men, and the eighth most common cause of cancer deaths in women.) When looked at in comparison to other cancers, these numbers don’t seem especially high. For example, lung cancer—the leading cause of cancer death in men and women—is expected to account for about 154,000 of the estimated 609,640 cancer deaths in the U.S. in 2018.

What’s disconcerting is that liver cancer is now the fastest-increasing cause of cancer death in the U.S. Incidence rates began rising in the mid-1970s, and they are expected to go up through at least 2030. “Liver cancer is the only cancer in the United States with incidence rates that continue to rise every year in men and women,” says Chari Cohen, a public health scientist and the vice president for public health and programs at the Hepatitis B Foundation in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

It’s not only in the U.S. that rates are climbing. A study published in the December 2017 JAMA Oncology found the incidence of liver cancer increased by 75 percent worldwide between 1990 and 2015. In many countries, liver cancer is among the top four causes of cancer death.

Variations in Risk Factors

A study published in the January/February 2018 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians found that in the U.S., about 71 percent of all liver cancer diagnoses can be attributable to preventable risk factors. The study, led by Farhad Islami, the strategic director for cancer surveillance research at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, found that about 22 percent of liver cancer deaths are attributable to cigarette smoking. (Previous studies had found that people who smoke are about twice as likely to develop liver cancer as nonsmokers.) Obesity is also driving up liver cancer rates. Earlier research found that from 2000 to 2003, about 26 percent of liver cancer cases were attributable to excess body weight; from 2008 through 2011, body weight could be linked to about 36 percent of the liver cancer cases that occurred. This suggests ongoing efforts to curb smoking and improve weight management to reduce deaths from other cancer types and heart disease could also help reduce deaths from liver cancer.

“Basically,” Islami says, “preventing exposure to those risk factors would mean a substantial proportion of liver cancer deaths—about 50 percent—could be prevented.”

Worldwide, hepatitis B—a virus that damages the liver and is spread through contact with infected blood, semen and other body fluids—is the most common cause of liver cancer. In the U.S., fewer than 5 percent of liver cancer cases are caused by hepatitis B, primarily because since 1982, children in the U.S. have routinely been vaccinated against the virus. In the U.S., hepatitis C has been a growing problem. Between 2000 and 2011, the proportion of liver cancer cases attributable to hepatitis C was 36 percent among African-Americans, 30 percent among Asians, 21 percent among Hispanics and 17 percent among whites. (The hepatitis C virus spreads through contact with infected blood.)

Islami’s study found that hepatitis C was responsible for about 6,450 (close to 25 percent) of liver cancer cases in the U.S. He says this figure reflects the large number of baby boomers with an undiagnosed hepatitis C infection. “This group is now in their 50s through 70s,” he says, “and that’s when we see liver cancer develop.”

Many of these cases could be prevented. The question isn’t whether liver cancer prevention methods are available, says Christina Fitzmaurice, an oncologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “The question is, how should these preventive efforts be rolled out?” In addition, she says, it’s important to know what the cause is in specific populations. “It doesn’t help to roll out hepatitis B vaccination if the biggest problem is alcohol abuse,” she says.

Newly available drugs that cure hepatitis C infection have the potential to bring liver cancer rates down. The drugs are taken daily, typically for eight to 12 weeks. But the first step, says Islami, is increased screening for hepatitis C, which is done with a blood test for antibodies to the virus. The cure is not cheap. Treatment ranges from $26,400 to $94,500 (depending on the type of drug used) and is not always covered by insurance. Currently, only about one-third of the people diagnosed with hepatitis C receive follow-up care, and less than 10 percent are successfully treated.

Outside the Risk Groups

For most cases of liver cancer, it’s easy to identify the probable cause. But for other patients, there is no clear reason why the disease found them. In 2000, Danielle Duran Baron, a Brazilian now living in the U.S., was diagnosed with anemia following a routine blood test for a cosmetic surgical procedure. It took nearly two years for her doctors in Brazil to identify the cause: fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC), a rare form of liver cancer that affects adolescents and young adults and makes up less than 1 percent of all primary liver cancers.

Baron was 28 when doctors found two tumors on her liver, one of which had grown to 18 centimeters. “It’s a miracle that it didn’t spread,” she says. It’s also a miracle that she made it through the surgery. During the difficult 12-hour procedure, she says, she “flatlined three times” and was infused with more than 20 pints of blood. Following surgery, like Gardea, she was treated with a transarterial chemoembolization—which was later shown to not benefit patients with FLC.

FLC is not associated with the traditional risk factors for HCC, like cirrhosis or hepatitis B or C, and most FLC patients don’t have the increased levels of AFP seen in patients with the most common form of HCC. At the time of Baron’s diagnosis, it wasn’t known what caused FLC to develop. But over the past five years, study findings have led researchers to link FLC to a genetic error that fuses two genes, DNAJB1 and PRKACA. Researchers hope this finding will one day lead to FLC-specific treatments.

Limited Treatment Options

Prevention is critical for reducing liver cancer deaths. There is no screening test for liver cancer and most people diagnosed with the disease have a poor prognosis: In the U.S., the overall five-year survival rate for liver cancer is only about 18 percent.

“The most important thing for people to understand,” says Fitzmaurice, “is that currently we are just not good at treating liver cancer. Surgery and targeted therapies [can be] effective, but it’s often found too late.”

Part of the problem, says Finn, is that whether or not the cancer has spread to other organs, there is often more than one tumor within the liver itself. Another problem is that many of the risk factors—like hepatitis B and C, alcoholism, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, a type of fatty liver disease—result in cirrhosis, life-threatening scarring that occurs when the liver tries to repair its own damaged tissue. “A cirrhotic liver is a premalignant organ,” explains Finn. “It is bad soil. So, if you take out the cancer, it’s likely to grow back.”

This diseased liver state must be factored into liver cancer staging, survival statistics and treatment options. A patient with a cancer that has not spread beyond the liver could have such extensive liver disease that surgery or other cancer treatments, including a liver transplant, are not an option, says Finn. For this reason, the liver cancer staging system also includes a measure of liver function known as a Child-Pugh score, which assesses the extent of liver disease.

When Gardea was diagnosed in 2013, Nexavar, which was approved in 2007, was the only targeted therapy available for treating liver cancer. Last year, two new options became available. In April 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded approval for the targeted therapy Stivarga (regorafenib) to include HCC previously treated with Nexavar. And in September 2017, the FDA granted accelerated approval to the immunotherapy drug Opdivo (nivolumab) for some patients with HCC. Other therapies—such as Mekinist (trametinib), already approved to treat certain types of metastatic melanoma, Zolinza (vorinostat), approved to treat cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and Cabometyx (cabozantinib), approved to treat advanced kidney cancer and a type of metastatic thyroid cancer—are being studied in liver cancer in clinical trials. “There is still a lot of work to be done,” says Finn, “but the future is exciting.”

A Shared Feeling of Good Fortune

Five years after her initial diagnosis, on a return trip to Brazil, Baron learned her cancer had recurred. While there, she had a second surgery; this time, the doctor removed the entire right lobe of her liver. Today, a decade later, the Laurel, Maryland, mother of two and chief marketing officer of a Baltimore-based nonprofit continues to be involved in efforts to bring more research attention and dollars to FLC. Annually, she sees a liver surgeon at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “Every year it’s hard,” says Baron. “But it also gives me a sense of purpose, and it’s always in my mind to live with that sense of purpose.”

Gardea continues to be fortunate. He developed a second tumor in his liver in 2013, but the surgery to remove it went well. And when medication needed to cure his hepatitis C infection became available, his insurance covered it. “I feel pretty good,” he says, even though one of his tumors appears to be growing again.

“During the time I’ve had this, I’ve had a few friends who got the same thing and died. In six months, they were gone,” he reflects. “I’m getting into my fifth year, and when I ask my doctor what our plan is, he says, ‘I don’t plan on you going anywhere for a long, long time.’” There’s no question, Gardea says, “I’m one of the lucky ones.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.