IN THE SPRING OF 2017, Patricia Hom was wrapping up a four-year medical residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California. But instead of continuing her career as a physician, Hom soon found herself in the unexpected role of a patient.

At the time, she was a 35-year-old mother of two boys, ages 15 and 16. She had been dogged by a persistent cough for months. Earlier in 2017, she had taken time off from work to visit an urgent care clinic. After examining her chest X-ray, the doctor sent her home with a diagnosis of walking pneumonia and a prescription for antibiotics.

By the end of June, Hom was feeling unusually tired. On top of the nagging cough, she struggled to breathe. Right after hitting the submit button on her medical board exam, she headed back to the urgent care center, where she had another chest X-ray. This time it showed fluid in both lungs and a mass on the left lung. Hom went straight to the emergency room for more testing, including a CT scan and bloodwork.

“It was the ugliest chest CT I’ve ever seen,” Hom says, describing the scattered nodules throughout her lungs in addition to the mass on her left lung. She went to a pulmonologist for more tests, including an analysis of the fluid in her lungs, but he resisted the idea that Hom, who was in her 30s and in seemingly good health, had lung cancer. He ordered a PET scan and referred her to an infectious disease specialist for what he thought could be an unusual infection.

When the specialist reviewed the PET scan results, he broke the news: Hom most likely had advanced lung cancer. Back at home that night, Hom logged into her online patient portal and opened her pathology report, which confirmed what the infectious disease specialist had suspected: Hom had lung adenocarcinoma, a type of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In addition, the cancer already had spread to the space surrounding both her lungs, a lymph node above her left collarbone, and the right side of her pelvis. She slammed her laptop computer shut.

A Deeper Dive

More than 220,000 people in the U.S. are expected to receive a diagnosis of lung cancer in 2020. In almost 60% of these cases, lung cancer is found after it has metastasized and spread to the other lung or distant parts of the body, such as the brain, bones or liver. The five-year relative survival rate for all patients, based on data from those diagnosed with lung cancer from 2010 to 2016, is just over 20%. In those whose cancer has spread to other organs and distant areas in the body, the five-year relative survival rate is less than 6%.

The good news is that substantial progress has been made in the past decade in treating NSCLC, which accounts for 80% to 85% of all lung cancer diagnoses. Many people with advanced NSCLC are living longer because of better therapies, even as treatment decisions have become more complex.

“About 10 years ago, if someone was diagnosed with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, the only treatment was chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation was added. So that was the treatment journey. It was very linear and uniform,” says Upal Basu Roy, vice president of research at LUNGevity Foundation, a national nonprofit dedicated to advancing lung cancer research and providing patient education and support. “Flash-forward to 2020, we know more about the biology of the disease. Certain mutations cause lung cancer and those mutations can be targeted. You can have a drug that blocks the effect of those mutations, and patients can show a remarkable response.”

One of the first questions oncologists ask now when treating people with lung cancer is whether the cancer carries a driver mutation for which there is a matched and approved drug, says Nasser Hanna, an oncologist at the Indiana University Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center in Indianapolis. Doctors can gain this information by performing a biopsy and having a sample of the tumor tissue analyzed in a lab. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved targeted therapies for seven mutations found in NSCLC tumors—with many more drugs and cancer targets being studied in clinical trials.

“We really need to know what the molecular profile is,” Hanna says. “Many [patients] with these mutations will gain a tremendous amount by starting with targeted therapy.”

Most of the targeted therapies come in pill form, making treatment more convenient than chemotherapy or radiation. They also generally come with fewer side effects. Among patients with lung adenocarcinoma, which is the most common type of NSCLC, about 30% of tumors will carry a driver mutation that makes the patients eligible for an FDA-approved targeted therapy, Roy estimates. Another 10% or so may carry a mutation that makes them candidates for clinical trials testing an experimental targeted therapy. For the approximately 60% of patients who aren’t eligible for targeted treatments, doctors are able to ask another question: What is the tumor’s PD-L1 status?

Sparking an Immune Response

Immune cells bind to PD-L1, a protein found on the surfaces of some tumors that prevents the immune system from attacking the cancer. Immunotherapy drugs work to block the interaction between PD-L1 and immune cells, freeing these immune cells to fight the cancer. Oncologists who treat patients with advanced lung cancers that lack driver mutations examine what proportion, if any, of a tumor’s cells carry PD-L1. If the proportion is high, the tumor might respond to immunotherapy.

A PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of 50% or greater is considered high, making treatment with Keytruda (pembrolizumab) an option, according to recommendations issued in January 2020 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). The ASCO guidance also suggests a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy as an option for patients who have low PD-L1 tumor expression and advanced NSCLC. In May 2020, the FDA approved two additional immunotherapies for the first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC: Tecentriq (atezolizumab), and a combination immunotherapy approach with Opdivo (nivolumab) and Yervoy (ipilimumab).

A study reported in the May 2019 Lancet found that patients with previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC survived significantly longer after taking Keytruda compared to patients who received chemotherapy, even when their PD-L1 score was as low as 1%. Those taking Keytruda also had fewer treatment-related adverse events compared to those taking chemotherapy (18% versus 41%). A 2018 study reported in the New England Journal of Medicine also showed that almost 70% of those who received a combination of Keytruda and chemotherapy survived for at least a year, compared to about 50% of those who received chemotherapy and a placebo.

Gregory Masters, an oncologist at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and Research Institute in Newark, Delaware, says that lung cancer patients receiving treatment with immunotherapy or a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy are typically re-evaluated every two to three months to see if their cancer is still responding. When scans show a response, patients can continue with the treatment, often for up to two years. Most patients who do respond to immunotherapies will develop resistance, but some patients can have a strong and sustained response. Masters and Hanna say that a significant number of people with advanced NSCLC who are treated with either a targeted drug or immunotherapy are now living five years or more. For those with a PD-L1 score greater than 50%, the five-year survival rate for patients treated with Keytruda is now 25% to 30%. Among patients who responded to Keytruda for at least two years, three out of four were alive at five years.

“For the first time, there are a substantial number of patients with stage IV NSCLC who are long-term cancer survivors,” Hanna says. “Many are living life as though they don’t even have cancer.”

A Treatment Journey

Soon after her diagnosis, Hom learned that her cancer carried a driver mutation in a gene called anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) that is found in about 5% of NSCLC adenocarcinomas. At the time of her diagnosis in 2017, Xalkori (crizotinib) was the only drug approved as a first-line treatment to target this mutation in NSCLC. However, another drug called Alecensa (alectinib) soon followed after clinical trial results, first reported at the June 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting, showed that the drug halted cancer growth for a median of 15 months longer than Xalkori, with fewer side effects.

Hom took Xalkori briefly before switching to Alecensa. She found the treatment left her exhausted, but there were soon signs that it was working. Scans showed she had just one spot on part of her sternum. The tumor in her lungs shrunk to what looked like a scar, and the fluid in her lungs disappeared. Within months, though, it appeared that the cancer in Hom’s bones was worsening. In winter 2018, doctors found evidence of cancer in her brain. Her physician increased the dose of Alecensa, but Hom soon found it hard to talk, write and read. She lost her balance and fell twice as the cancer in her brain progressed.

By then, Hom had another treatment option. In November 2018, the FDA approved Lorbrena (lorlatinib) for patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC who had progressed on Alecensa or another ALK inhibitor. The approval was based on a study showing about a 50% response rate in patients who had progressed on earlier treatment. The study also showed that the drug worked in 60% of patients to help shrink lesions in the brain.

In the summer of 2019, Hom switched to Lorbrena. The cancer appeared to be stable for a while. “At one point, lorlatinib was looking like it had given my life back, but that was short-lived,” Hom said. In August 2020, she learned the cancer in her lungs was progressing, which caused a series of strokes that led to a 12-day hospital stay. Doctors also discovered a tumor in an ovary. At the end of August, she was still taking Lobrena to control the cancer’s growth in her brain, but she also started on chemotherapy.

New treatments, such as ALK inhibitors, have helped patients live longer with a lethal disease. A study in the April 2019 Journal of Thoracic Oncology reported that, among patients treated for advanced ALK-positive lung cancer at UC Health University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora between 2009 and 2017, 50% were alive 6.8 years after diagnosis. In contrast, only 2% of people with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC survived for five years from 1995 to 2001. Patients in the study cycled through a number of drugs targeting ALK after the first one stopped working.

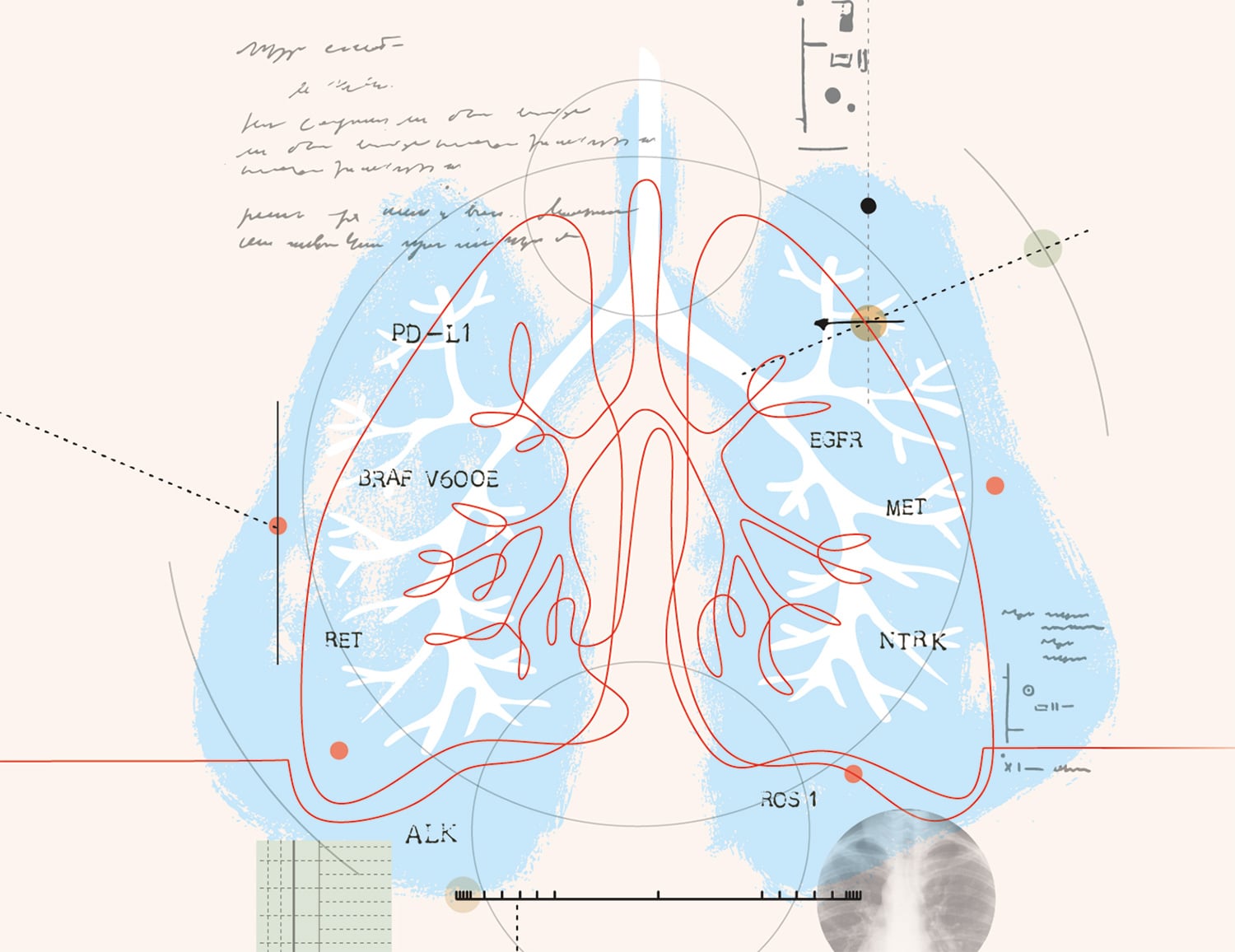

A variety of tumor mutations help lung cancers to grow and spread.

Organizations such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) suggest all patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have tumor testing to identify mutations that could qualify them for targeted treatments. The following is a sampling of known biomarkers and their treatments.

EGFR

Mutations in EGFR, present in about 15% of NSCLCs, cause the cancer cells to grow quickly. Five drugs, called tyrosine kinase inhibitors, are approved for EGFR-positive NCSLC. They are Gilotrif (afatinib), Iressa (gefitinib), Tagrisso (osimertinib), Tarceva (erlotinib) and Vizimpro (dacomitinib).

ALK

About 5% of NSCLCs have a change in the structure of the ALK gene or make too much ALK protein on the cancer cell surface. Drugs approved for the initial treatment of ALK-positive NSCLC are Alecensa (alectinib), Alunbrig (brigatinib), Lorbrena (lorlatinib), Xalkori (crizotinib) and Zykadia (ceritinib).

ROS1

ROS1 rearrangements, found in about 2% of NSCLCs, can drive the growth of cancerous cells. There are four FDA-approved drugs that target the ROS1 gene change: Lorbrena, Rozlytrek (entrectinib), Xalkori and Zykadia.

BRAF V600E

Estimated to occur in 2% to 3% of NSCLCs, the BRAF V600E mutation leads to the production of too much of a growth-signaling protein. Two drugs are used to treat this cancer type, often in combination: Tafinlar (dabrafenib) and Mekinist (trametinib).

NTRK

About 1% of NSCLCs carry fusions in NTRK genes. This type of tumor may respond to Rozlytrek or Vitrakvi (larotrectinib).

MET

About 3% to 4% of NSCLC patients have mutations in the MET gene that lead to MET overexpression. Tabrecta (capmatinib) is approved to treat these NSCLCs.

RET

About 2% of NSCLCs have a fusion in a gene called RET. Retevmo (selpercatinib) is the only drug approved to treat these tumors.

ASCO and the NCCN also recommend that all advanced lung cancers, and especially those lacking a driver mutation, be tested for expression of PD-L1, which influences the likelihood that a cancer will respond to immunotherapy treatments. Most often, patients do not receive targeted treatment and immunotherapy together. “Most of those with driver mutations aren’t receiving immunotherapy [today], but that could change,” says Gregory Masters, an oncologist at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and Research Institute in Newark, Delaware.

Looking to the Future

Many patients who initially respond to treatment for NSCLC will face a new round of questions down the road, says Roy Herbst, a medical oncologist at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut. “If someone has had front-line therapy, whether it’s chemotherapy, immunotherapy or targeted therapy, and it stops working, what do you do next?” he asked.

If no clear alternatives are available, the Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP), a National Cancer Institute-sponsored study offered at more than 700 hospitals and physician practices across the country, groups people with advanced NSCLC to receive targeted treatments based on the molecular characteristics of their tumors. Launched in 2014, Lung-MAP is an umbrella trial, a study that tests how well drugs work in patients with the same type of cancer but different mutations, which allows many drugs to be tested at one time. Patients who don’t qualify for targeted treatments based on their tumor’s unique profile can receive other treatments through the trial.

Since it first launched, Lung-MAP has tested 12 novel therapies in patients. While none of this research has led to an FDA approval, Lung-MAP has helped pinpoint whether certain drugs are worth pursuing for different types of NSCLC.

“I’m as optimistic as I’ve ever been about treating lung cancer,” Masters says. “We’re providing more options for more patients with better quality of life and longer survival. It’s not all patients—there’s still work to do—but it is a time of optimism for treating lung cancer and for patients.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.