AFTER HER TREATMENT for stage III breast cancer, Kim Builta, of Austin, Texas, had been in remission for seven years. But in 2010, she had scans that revealed a mass in her hip, which meant she had incurable stage IV cancer.

She tried several different treatments, including the oral chemotherapy drug Xeloda (capecitabine), which kept her cancer stable from 2012 to 2019. Each time the cancer progressed, she had a biopsy and tumor testing that showed she had hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. However, after progression on Verzenio (abemaciclib) in January 2023, she learned about a new way that doctors were characterizing her tumor.

“That’s when I learned I was HER2-low,” Builta says, meaning her cancer expressed some HER2 proteins but not enough to classify it as HER2-positive. “When I was diagnosed [with metastatic cancer] almost 15 years ago, the testing was not anywhere near what it is now. I don’t think they even knew what HER2-low was back then. It was just either you did or you didn’t have it.”

Katy Bell, of Coventry, Rhode Island, has a similar story. She was diagnosed with stage III hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer in 2012. While taking Xeloda in 2016, she learned the cancer had spread to her liver. She got a biopsy, which confirmed her cancer was HER2-negative, and cycled through different treatments. She eventually landed on a combination of Verzenio and the hormone therapy Femara (letrozole). In 2022, with no evidence of active disease, Bell stopped taking Verzenio because of severe diarrhea, the drug’s most common side effect. But she kept taking Femara and had routine scans to watch for signs of progression. About two years later, after running the 2024 Boston Marathon to raise funds for Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, she started having excruciating pain in her glutes and lower back. A scan revealed a fracture in her pelvis—likely the result of her intensive marathon training—but it also showed a small spot on her pelvis. The cancer had progressed. She had been feeling so healthy and fit as a runner that she says this latest turn “felt like a new diagnosis.”

Because the growth was so small, her doctors examined tissue from a previous biopsy taken from her liver in 2016. Her cancer that was once considered HER2-negative was now categorized as HER2-low. Noting how her cancer didn’t grow while she took the CDK4/6 inhibitor Verzenio previously, her oncologist recommended she try another CDK4/6 inhibitor called Kisqali (ribociclib) and added that the cancer’s HER2-low status was “a really good thing because if the Kisqali stops working, we have more options,” she says.

Targeting HER2

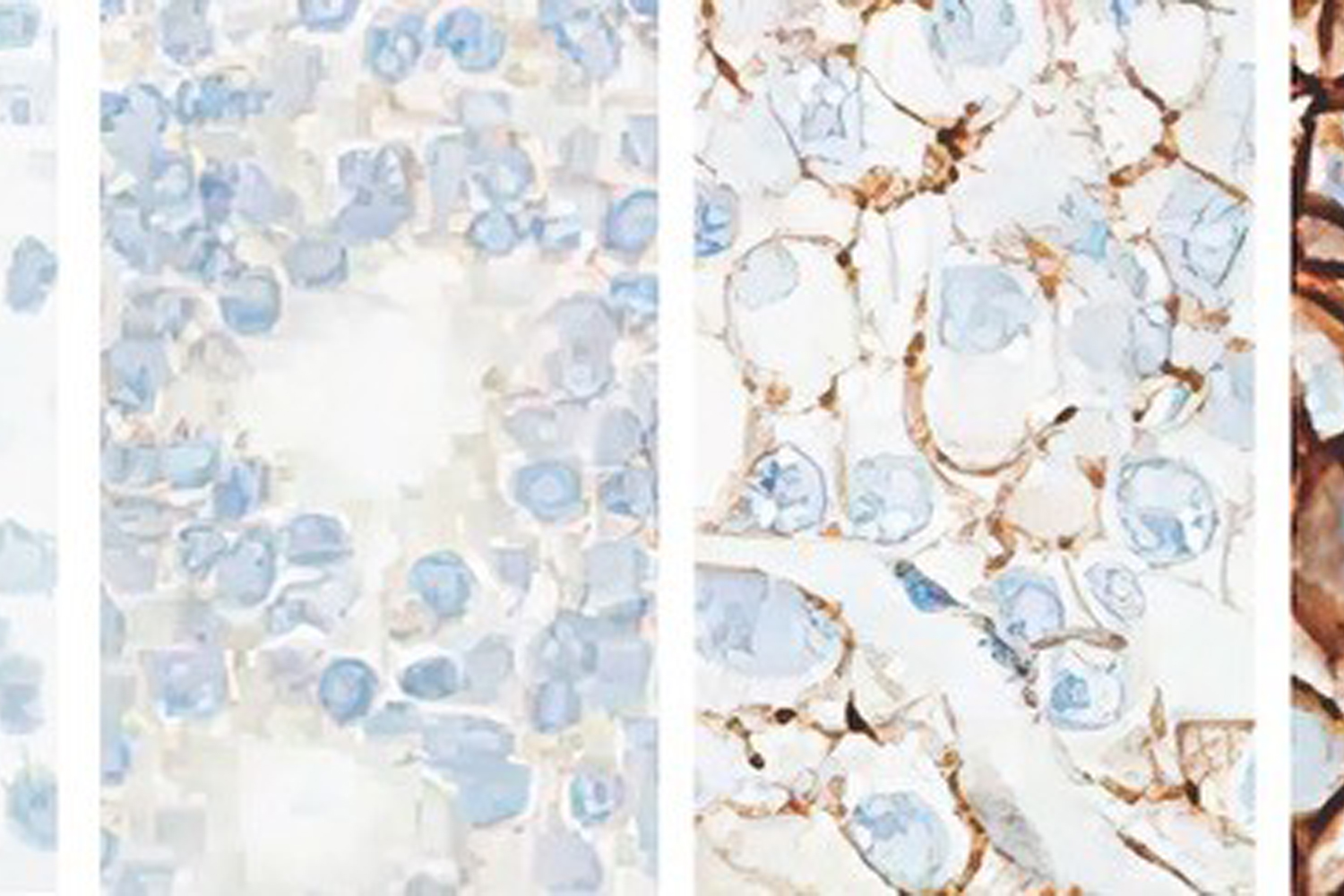

About 1 in 5 breast cancers are HER2-positive, having abnormally high amounts of HER2 protein on their surfaces. Excess HER2 also is found in other cancer types, including some cases of gastric, ovarian, lung and colorectal cancers. Because the protein spurs the growth of cancer cells, oncologists once relied on this biomarker to gauge prognosis. That changed in September 1998, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Herceptin (trastuzumab), an antibody and the first HER2-targeted treatment for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. HER2-positive cancers are defined as having a HER2 score of 3+ on immunohistochemistry (IHC) tests. (IHC tests use staining to quantify specific proteins in tissue samples. HER2 testing can also include fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which tests for HER2 gene amplification, if the IHC score is 2.) When administered with chemotherapy, the combination of HER2-targeted therapies Herceptin and Perjeta (pertuzumab) has extended survival from months to years. But the benefits of these targeted therapies were only seen in those whose cancer expressed high levels of HER2 proteins.

“For a long time, HER2 was defined as a binary [yes or no] system,” says medical oncologist Arya Roy, who specializes in breast cancer at Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus. “But even if you say [a cancer is] HER2-negative, it’s not completely negative. There may still be some staining of the HER2 [protein], but it’s just not up to the point of calling it HER2-positive. We’ve realized HER2 is a spectrum rather than a binary value.”

Your doctor can help you understand your HER2 status and treatment options.

Choosing among treatment options when you or a loved one has metastatic breast cancer that’s HER2-low or -ultralow is a challenge. Here are some questions for your oncologist that may help you decide:

- What is my HER2 score?

- What does my HER2 score mean for my treatment options?

- Does my cancer have other mutations for which there are targeted treatment options?

- If my cancer has spread to a new site, should I undergo a biopsy and biomarker testing again?

- Am I a good candidate for Enhertu?

- What are the common side effects of Enhertu, and how do they compare with other treatment options?

- How will treatment affect my quality of life?

- If I take Enhertu and it doesn’t work for me, what would you recommend for me next?

This distinction became important after the FDA approved the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) Enhertu (trastuzumab deruxtecan) for locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer that expresses low levels of HER2. In the phase III clinical trial that led to that August 2022 approval, people with locally advanced or metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-low breast cancer treated with Enhertu had a median progression-free survival of 10.1 months, compared with 5.4 months for those treated with chemotherapy. The study showed similar survival benefits in hormone receptor-negative, HER2-low disease. In January 2025, the FDA expanded Enhertu’s approval again to include metastatic breast cancers with minimal levels of detected HER2, called HER2-ultralow. HER2-ultralow breast cancers have IHC scores of 0, with faint or incomplete staining in 10% of cancer cells or less.

Enhertu links the Herceptin antibody trastuzumab to the chemotherapy drug deruxtecan. The reason this drug, unlike Herceptin, can be effective even when HER2 levels aren’t unusually high is because the trastuzumab isn’t the cancer-fighting ingredient. The antibody’s job is to target any HER2 protein on the cancer’s surface and deliver the linked chemotherapy straight to a tumor. Once inside, the cancer-killing chemotherapy in the ADC is released to attack cancer cells. Enhertu may work when HER2 levels are extremely low due to what’s known as a bystander effect, Roy explains.

“Once this compound goes into the cells that have the HER2 expression, it kills those particular cells,” she says. “In addition to that, this will also release some chemotherapy [drug] to the neighboring cells, [including those] that do not have HER2 expression, so that will kill the neighboring cells as well.”

Expanding Options, Improving Outcomes

While Enhertu is so far the only HER2-targeted option approved for treating HER2-low or -ultralow breast cancers, Roy says the new breast cancer designation is already having a significant impact, particularly for women with advanced breast cancers previously defined as HER2-negative who find themselves running out of treatment options after cancer progression. Half of all breast cancers are estimated to be HER2-low, and at least 60% of advanced breast cancer cases meet the criteria for HER2-low or -ultralow.

In most instances, people who were diagnosed with HER2-negative breast cancer before Enhertu’s approval can learn their IHC score by checking their previous pathology reports. Still, Roy often tests for HER2 expression from new metastatic sites whenever the cancer progresses to a new organ. “HER2 expression is actually dynamic and can change over time,” she explains.

Most pathology reports will include whether cancer is HER2-positive or HER2-low, says Roy. It remains less common for reports to indicate if the cancer is HER2-ultralow. “If the report shows a patient doesn’t have any HER2 expression, [an IHC score of 0], I will actually reach out to the pathologist to see if this patient has HER2-ultralow expression, which means any staining of HER2,” she says. “For patients, it’s important to ask their providers whether they have any HER2 expression. It’s always good to double-check.”

Staying Ahead

Enhertu is just one of many options a patient might consider if their HER2-low or ‑ultralow breast cancer progresses, says Naoto Ueno, a breast medical oncologist and director of the University of Hawai’i Cancer Center in Honolulu. Treatment options for advanced breast cancers may include chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy, such as CDK4/6 inhibitors. Other targeted therapies may be considered when breast cancers carry additional mutations, such as AKT, ESR1 or PI3K. Ueno says the oral chemotherapy Xeloda also plays an important role in metastatic breast cancer treatment given that it is well-tolerated and comes in pill form, which makes it more convenient than many other types of chemotherapy.

“You need to put this all in the context of your physical condition, the load of the disease, and genetic changes that would determine treatment options,” Ueno says. “If it’s HER2-low, then Enhertu will become a potential choice that exists. But there’s really a lot of different discussions and guidelines to determine [in each case] whether to give this drug or not.”

In an analysis published May 11, 2025, in the Oncologist, Ueno and his colleagues found patients who received Enhertu remained on treatment for twice the amount of time as people who received chemotherapy. Those who received Enhertu reported having longer sustained periods without pain than those who received chemotherapy. Enhertu did generate more patient reports of nausea and vomiting, which Ueno says is a reminder of the importance of managing those side effects for those taking the ADC.

While a HER2-low cancer designation could open the door to another possible treatment option, the classification doesn’t mean the cancer is any more or less likely to respond to other treatments, such as radiation, chemotherapy or hormone therapy, says Sarat Chandarlapaty, a breast medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “All of that isn’t any different because a cancer is HER2-low,” he says, “and that is important for people to recognize.”

Other questions remain, including whether people with HER2-low or -ultralow breast cancers might benefit from using Enhertu sooner. Currently, the drug is reserved for people with HER2-low or -ultralow cancer that has progressed on earlier lines of treatment. However, researchers are examining Enhertu’s potential for treating earlier-stage HER2-low breast cancer. In addition, patients with HER2-low cancer may also have other tumor mutations that could respond to different targeted treatments. In most cases, the decision to try one therapy over another depends on the individual patient’s condition.

Bell, who recently turned 49, still takes Kisqali, along with the estrogen-blocking drug Faslodex (fulvestrant), and has regular scans. In the summer of 2024, she received radiation to her pelvis. Within the last year, she has had no signs of cancer progression. But she knows she can try Enhertu if her cancer stops responding to her current treatment.

In 2023, when Builta learned her cancer expressed enough HER2 protein to be considered HER2-low, her oncologist recommended she try Enhertu. After taking a couple of doses of the drug, she ended up in the hospital with pneumonitis, “so we quit that very quickly,” she says. Pneumonitis, also known as inflammation of lung tissue, is a known and potentially serious or even life-threatening side effect of Enhertu. Another dangerous side effect is interstitial lung disease, which is scarring of the lungs. Because of these side effects, patients who take Enhertu are typically closely monitored for respiratory symptoms. Based on blood tests showing her cancer also carries an ESR1 mutation, Builta is currently receiving Orserdu (elacestrant), which was approved by the FDA in 2023 for advanced or metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer with this mutation.

With her two children now grown, Builta says she tries to “stay ahead of the research” and balance the benefits of treatments with the side effects to maintain her quality of life. Having recently turned 59 and now on her ninth line of treatment, she encourages others diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer to remain optimistic and proactive. “Just because one drug doesn’t work for you doesn’t mean the next one won’t,” Builta says. “HER2-low wasn’t even a thing when I was first diagnosed, so you have to believe that there can be something new around the corner.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.