Staff from a food bank brought surprising news to the team at New England Cancer Specialists (NECS). The food bank professionals, whom NECS invited to share information about food insecurity in the area, mentioned something the doctors didn’t expect: The food bank’s main problem wasn’t a lack of food, but getting food to the people who needed it. People had to come to the facility to pick up the food, and transportation, time and social stigma were barriers between hungry people and the groceries they needed.

In Maine, where NECS is located, nearly 14% of residents are affected by food insecurity, higher than the national average of about l2%. NECS has three locations, in Kennebunk, Scarborough and Topsham. The doctors at NECS wondered how many of their patients weren’t able to access the food they needed. They discovered a lack of information about how food insecurity affects cancer patients, so they began their own research.

The practice added questions to its patient survey, asking patients how frequently during the previous year food ran out and they couldn’t afford more or they had concerns about that happening. The surveys revealed that between 100 and 200 patients, fewer than 10% of their total patients, dealt with food insecurity. The practice discovered that these patients were less likely to remain on treatment than others. The association between food insecurity and stopping treatment was highest for patients with early-stage breast cancer, who sometimes remain on expensive oral medication, such as an aromatase inhibitor, for years.

As a result of these findings, the center partnered with the food bank to provide groceries for patients experiencing food insecurity. Bags of nonperishable foods, discreetly packed in plain brown bags, could be picked up at the on-site pharmacy when patients picked up their medicine.

“Patients at some point have to make a decision about how they’re going to eat and how they’re going to afford their treatments,” says Christian Thomas, an oncologist at NECS. “What we could show is that when you give these patients food, then they stay on treatments as long as those who do not have food insecurity.” The researchers hope to collect more data before publishing their findings.

The project caught the attention of the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC), which awarded the group a 2019 ACCC Innovator Award. The awards honor “ingenious ideas and pioneering achievements” from ACCC member centers.

A study published in the August 2019 issue of the Journal of Cancer Survivorship revealed that approximately 8% of 1,022 cancer survivors who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys experienced food insecurity, with rates higher in some groups, including survivors who were uninsured, young survivors, parents with children at home and Hispanic or black survivors. Another study, published in the May 2018 issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine, examined the association between chronic illness and food and housing insecurity, finding that cancer brings an increased risk of food insecurity.

Food insecurity can affect cancer patients in many ways, says Irene Hatsu of Ohio State University in Columbus, who studies the impact of food insecurity on chronic diseases. “Anxiety and depression have an association with food insecurity, so that would affect somebody who is already going through the difficulty of a cancer diagnosis. And if their thoughts are always on ‘What am I going to eat?’ and ‘Will I have enough food to feed my family?’ then it takes their minds away from being able to follow their treatments.”

The problem is one facet of the larger issue of financial toxicity. Medical appointments and side effects of treatments can interfere with work and may result in lost income. And cancer care can be expensive, even for patients who have health insurance. NECS found that 97% of their patients who were food insecure had health insurance, but insurance plans can have high deductibles or high copays. The expense of treatment means that patients make tough decisions when weighing what they can and cannot afford.

“They’re having to juggle between choosing treatment or buying food,” Hatsu says. “People would have to choose between providing for themselves nutritionally or providing for themselves medically.”

If patients struggle with affording both food and treatment, Hatsu encourages them to talk with their clinicians. She says that it helps patients to have a partner who can guide them to the many private and federal resources that offer assistance. “A cancer diagnosis is a difficult thing, so have someone alongside you to help you find food resources,” Hatsu says.

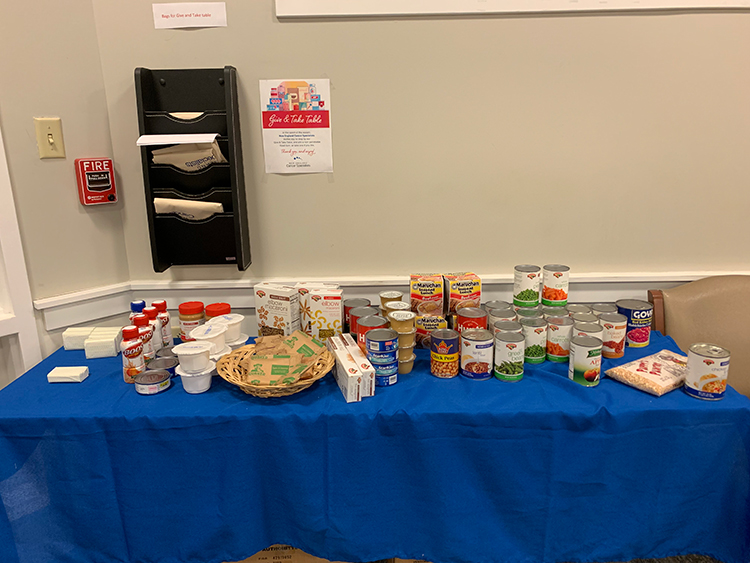

New England Cancer Specialists set up a giving table so patients could take or donate items during the holiday season. Photo by Torrina J. Lavoie

The food insecurity project at NECS continues. The staff there has been so supportive of the work that they now fund this project independently, taking up a collection among themselves instead of partnering with the food bank. Before Thanksgiving, they added a new feature: a giving table in the treatment area. During the holiday season, patients were welcome to leave or take any item they’d like. In addition to the food offered on the table, toiletries have been in-demand items.

Now, the team is applying for a grant that would allow them to put the infrastructure in place to continue its food insecurity project, as well as to do additional research. Practices in neighboring states have expressed interest in replicating their project.

“The amount of money that’s needed to do something like this is ridiculously little compared to [other expenses],” Thomas says. “[The money spent on] a single vial of an expensive immunotherapy could run the whole project for a year. We’re paying all this attention to curing people’s cancer, but some people can’t have three meals a day.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.