THE PROSPECT OF A VACCINE that offers protection from cancer might seem too good to be true, but it’s not. Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes virtually all cervical cancers, around 95 percent of anal cancers, roughly 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers, and many forms of vaginal, vulvar and penile cancer. The HPV vaccine Gardasil 9 safeguards recipients against seven types of HPV that cause around 90 percent of cervical cancers, 90 percent of HPV-related anal cancers and some vulvar and vaginal cancers. The vaccine also protects against two types of HPV that cause genital warts. And it protects against strains of HPV that have been linked to some oral and penile cancers.

Cervical cancer has decreased in the U.S. over the years due to routine screening, but HPV-related oropharyngeal, anal and vulvar cancers are on the rise. According to a report released Aug. 24 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 30,115 cases of HPV-related cancers were reported in the U.S. in 1999, rising to 43,371 by 2015.

“People have been clamoring for years for a cancer vaccine,” says Electra Paskett, an epidemiologist who serves as the director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at Ohio State University’s College of Medicine in Columbus. “Now we have a vaccine, and it’s not being used.”

The CDC recommends that children be routinely vaccinated with Gardasil 9 at 11 or 12 years of age, administered as two doses. For those starting the vaccine series at age 15 or older, three doses are recommended. However, the CDC reports that in 2017, only 49 percent of American adolescents between ages 13 and 17 were up to date. Widespread immunization makes it more difficult for a contagious disease to spread from person to person and protects even those who cannot or choose not to be vaccinated, a concept called herd immunity. A minimum of 80 percent vaccination coverage is required to achieve herd immunity, Paskett says.

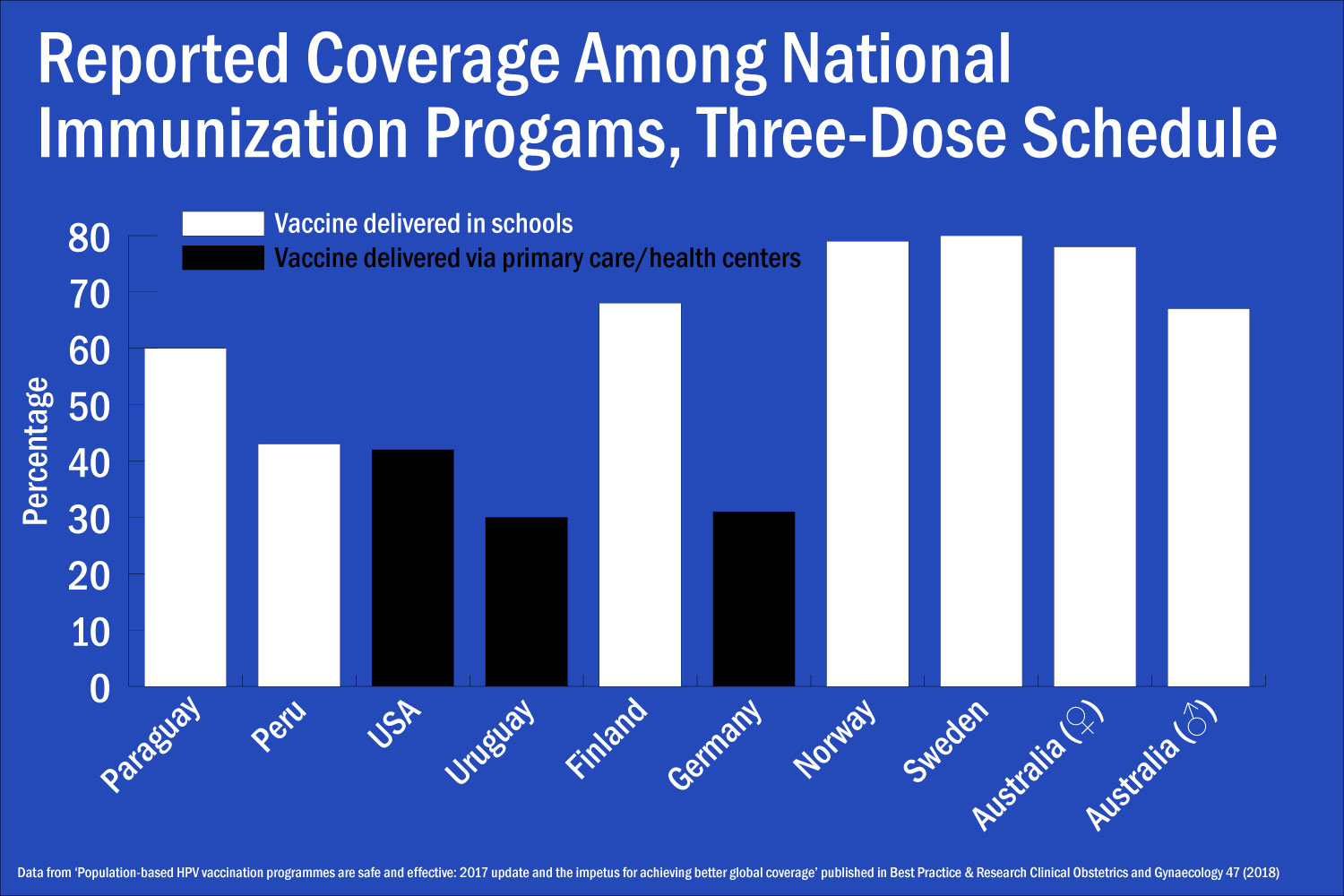

Around a quarter of the countries that report the outcomes of their HPV vaccination programs say they are able to completely vaccinate more than 80 percent of those targeted, according to a paper published in the February 2018 issue of Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. However, not all countries target both men and women, and often rates of vaccination are lower in males even when they are targeted in a vaccination program.

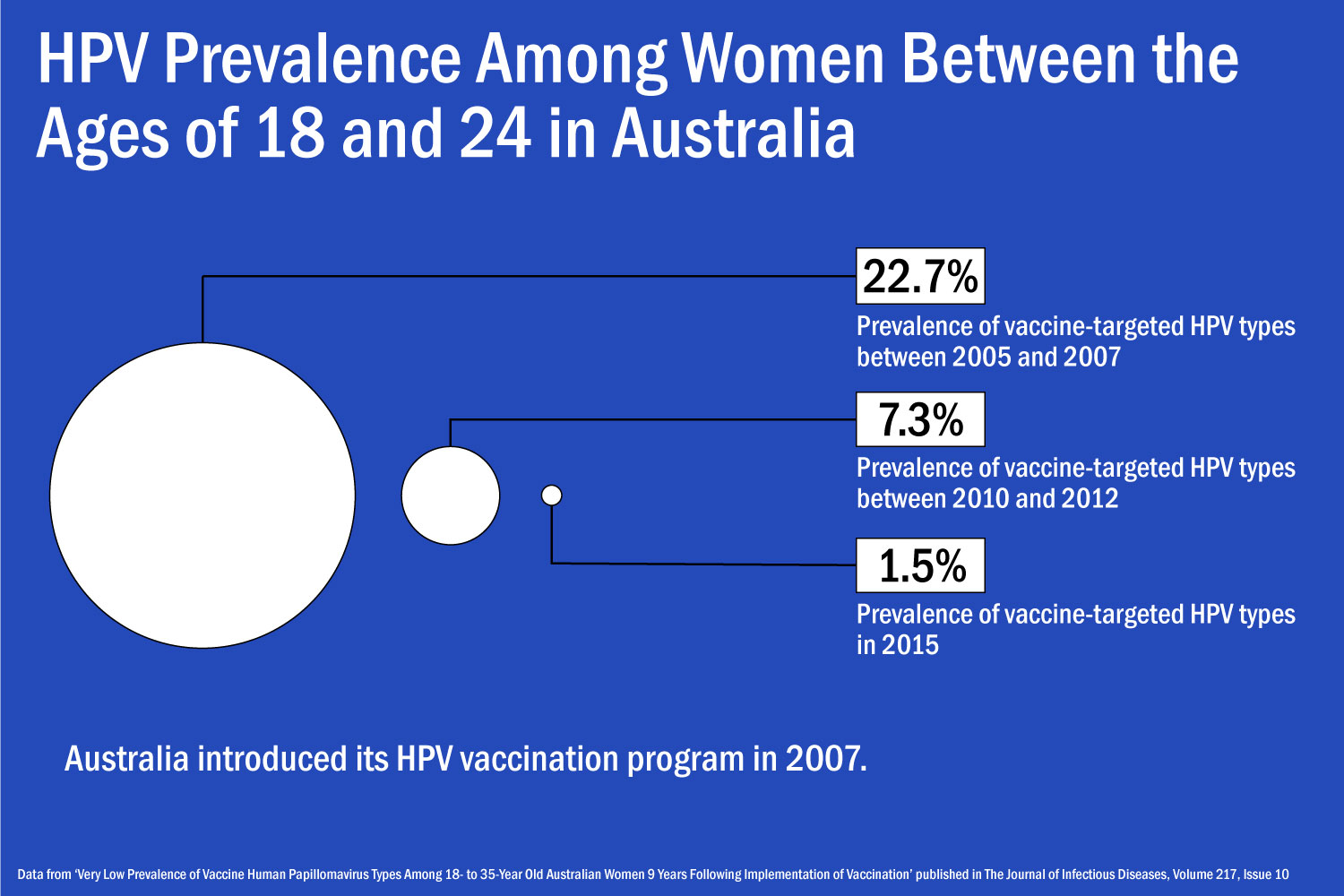

Australia has become a poster child for success in administering the HPV vaccine both to females and males. In April 2018, The Journal of Infectious Diseases published research detailing the country’s efforts to immunize the population. In 2016, 79 percent of 15-year-old girls and 73 percent of 15-year-old boys had received the two doses required for vaccination. It’s now thought that Australia could reduce the current annual rate of cervical cancer diagnosis from seven cases per year to less than one case per year by 2066, according to research published by The Lancet Public Health on October 2.

Joe Tooma, CEO of the Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation (ACCF), says that two circumstances distinguish Australia from the U.S.: “total political and financial support” for the program from the Australian federal government, and what he describes as a “general acceptance” among the public that the HPV vaccine is safe and effective.

Crucially, most Australian children receive the HPV vaccine in school. Administering the vaccine during schooltime is an efficient way to reach a broad swath of the local community at once, and given that two or three doses are required, it’s a convenience for parents who would otherwise have to make multiple trips to their child’s physician. The study published in Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology points out that countries that use school-based vaccination programs have an average of 20 percentage points higher coverage than those that rely on primary care or health centers.

Meanwhile, the success of cervical cancer screening in the U.S. and other countries in the developed world may have decreased people’s sense of urgency about getting the HPV vaccine.

Tooma notes that cervical cancer is much more common in the developing world than in richer countries due to disparities in screening. In an effort to decrease cervical cancer in the developing world, his organization has vaccinated more than 31,000 girls and screened and treated thousands more women in Rwanda since 2007. It also runs programs in Bhutan, the Pacific island nations of Vanuatu and Kiribati, and elsewhere.

Developing countries are less likely to have HPV vaccination programs than higher-income countries. But those programs that do exist in developing countries are often very successful.

“In my experience, almost everybody I talk to knows someone who has died from cervical cancer, whether it’s their mother, sister, auntie, next-door neighbor, schoolteacher or someone they work with” says Tooma. “If the vaccine or screening were available, it would be embraced enthusiastically by nearly 100 percent of the target population, because they know that it could save their lives and make sure children will not lose their mother. The village and community would be stronger because the women would be healthier.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.