This story was updated March 18 to add comment from thoracic oncologist Nathan Pennell and to add details about a new study from the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. It was updated March 23 to add comments from breast oncologist Stephanie Graff.

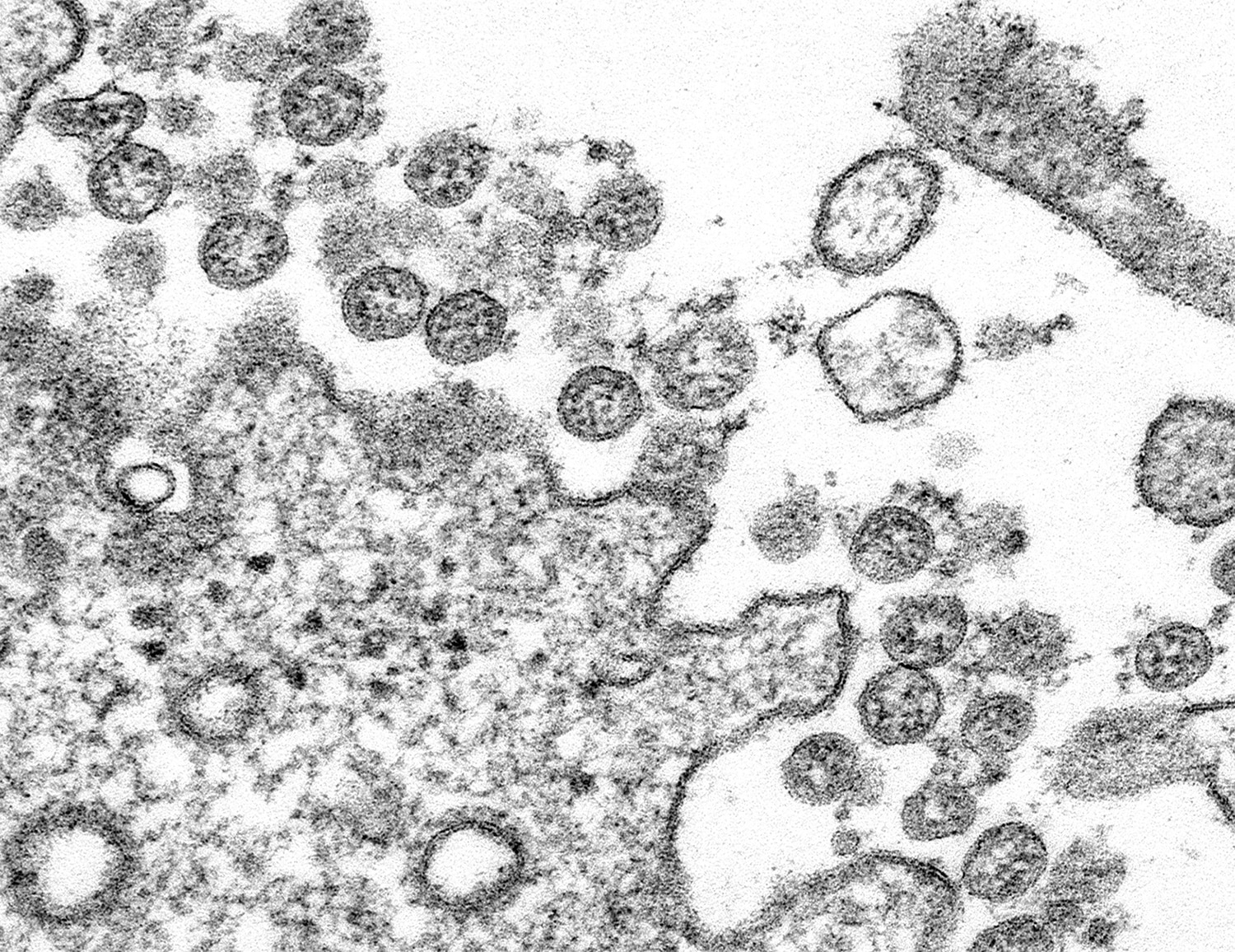

As the new coronavirus spreads, cancer patients are wondering what it means for their health and treatment.

If cancer patients are infected with the coronavirus, they are considered to be at elevated risk of severe cases of the disease, referred to as COVID-19, caused by the virus. The group at highest risk are patients with blood cancers and those receiving bone marrow transplants. But any patients in active treatment for cancer are at elevated risk, as are patients who are elderly, said Steven Pergam, medical director of infection prevention at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), in an article published March 13 in the Cancer Letter. Comorbid conditions like respiratory or cardiac problems, which many cancer patients have, also put patients at increased risk from COVID-19, Pergam explained to Healio.

Cancer patients—along with many other Americans—are trying to slow the spread of the virus by staying at home. “People with cancer should really make every effort to practice social distancing since they are [at] higher risk to have severe COVID-19,” says breast oncologist Tatiana Prowell of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

For More Information

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing information on COVID-19 and advice for those at high risk of severe cases of COVID-19.

The National Cancer Institute has information on what people with cancer should know about COVID-19.

Cancer Today has more coverage of the coronavirus available here.

In practice, Prowell says, this means ordering groceries online, ordering meals to be delivered, or asking a friend, neighbor or family member to get things from the store or pharmacy. If people with cancer must go out, for instance, to pick up a prescription, she recommends using a drive-through.

“Physical distancing lowers the risk of infection and how quickly it spreads,” explains Matthew Katz of Radiation Oncology Associates in Lowell, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire. “At a community level, it permits health care staff to avoid being overwhelmed with a surge. If health care workers have too many people to treat at once, more people may die. Cancer patients are at a higher risk than most.”

Everyone—cancer patient or not—needs to help avoid the spread of the virus, says oncologist Stephanie Graff, director of the Breast Cancer Program at Sarah Cannon at HCA Midwest in Overland Park, Kansas. “The best protection right now is to just stay home,” she says. She also urges everyone to “continue to be rigorous” about washing their hands, covering their coughs, wiping down high-traffic areas like door handles, cell phones and computers, and not touching their faces, noses and mouths.

But amid instructions to stay inside, cancer patients may wonder if they should venture out for doctor appointments and treatment.

Many cancer patients really do need to come in for urgent treatment, but many doctors are rescheduling nonurgent follow-up appointments. A Twitter poll directed to oncologists by Graff on March 15-16 found that 69.8% of 540 respondents were reducing clinic visits for routine follow-up care, while an additional 23.3% were “trying to make it happen” or “waiting admin direction.”

Cancer centers have also announced they are rescheduling noncritical visits and increasing use of telemedicine. They are also taking such measures as asking patients to contact their care team in advance of coming in if they have certain symptoms, screening for symptoms of COVID-19 at entrances, limiting visitors, and canceling volunteer shifts and gatherings. Leaders of cancer centers have shared in the Cancer Letter what they are doing to prepare for COVID-19.

Nathan Pennell, director of the Cleveland Clinic Lung Cancer Program, told Cancer Today that his group is ramping up telemedicine and recommending that cancer patients delay in-person visits to their doctor, “such as routine checkups or even surveillance visits with CT scans,” when possible. For instance, someone who is due for their annual scan and feeling well might wait another month to get their scan. “Or they can get the scan alone and then discuss the results on a virtual visit,” he says.

Patients will still get lung cancer surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. “We do not anticipate any changes in treatment over this,” Pennell says. “All lung cancer patients who need treatment should still be able to get it.”

Katz says his practice has deferred all routine follow-up appointments. Instead, he is calling his patients to check on them. “We are exploring telemedicine, but for now a simple telephone call goes a long way to reassure my patients that I’m always here to help them, even when they can’t see me in person,” he says.

Prowell generally advises that people with cancer should call their doctor’s office one to two days in advance of appointments to ask if they should come. “Things are changing rapidly, everyone is busy, and they may not have time to call all of you,” she said in a tweet. Katz advises patients in doubt to ask if a routine visit can be done at a later time.

Experts from SCCA on March 17 published an article in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network on cancer management during the pandemic. “Responding quickly and confidently to the COVID-19 crisis is the health care challenge of our generation,” co-lead author F. Marc Stewart, medical director of SCCA, said in a press release distributed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) in advance of the paper’s publication. “Our overarching goal is to keep our cancer patients and staff safe while continuing to provide compassionate, high-quality care under circumstances we’ve never had to face before.”

Anticipated challenges, according to the paper, are staff shortages, limitations on resources like hospital beds and protective equipment, and effects from travel bans, such as reduced access to international donors for bone marrow transplants. The authors say in the paper that SCCA has rescheduled “well” visits or switched them to telemedicine visits and deferred second opinion consultations when the patient is already being treated elsewhere.

“The more difficult decisions are clinical decisions regarding delay of treatment for patients who are currently undergoing chemotherapy or about to begin,” the authors write. They say that post-surgery chemotherapy with curative intent for patients with solid tumors should proceed. For patients with aggressive blood cancers, treatments like bone marrow transplants or cellular immunotherapies like CAR-T cell therapy often cannot be delayed. The risks of treatment delays for patients with metastatic cancer will need to be considered while making decisions about chemotherapy. Delaying surgery might be warranted in some scenarios. For instance, a patient with early-stage hormone receptor-positive breast cancer might be able to delay surgery and take hormone therapy for several months.

“I urge cancer patients to touch base with their doctor, their care team,” says Graff. “It is important right now that we balance the risk of COVID-19 (coronavirus) infection with each person’s individual cancer treatment plan. Know that every doctor I know is making these decisions themselves and communicating them to their team, so if you are asked to reschedule, it is likely because your doctor felt that was in your best interest.”

The NCCN is providing COVID-19 resources on a web page. The American Society of Clinical Oncology is currently compiling answers to frequently asked questions from oncology professionals on treatment and COVID-19.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.