“LIZA, I NEVER THINK OF YOU as someone who had cancer. Just because you had cancer doesn’t mean it has to be part of your identity,” a capoeira instructor announced to me around the time of my second of three primary breast cancer diagnoses in 2005.

This apparently benign and well-intentioned comment took up residence in my brain. Looking back on the 26 years since my first diagnosis in 1994 at age 29, I have come to understand the true nature of remarks like these. They were only about me if I were to imagine myself vanishing behind a mirror to the denier’s worst fears. When people tell you that your catastrophic diagnosis doesn’t have to be a part of your identity, they are squeezing their eyes shut, sticking their fingers in their ears, and squealing “la la la” in the face of reality.

For my first cancer, I had no TripAdvisor or Lonely Planet guide (oh, was it ever lonely) to what Susan Sontag called the kingdom of the ill in her 1978 book Illness as Metaphor. I didn’t even know I was heading there: I had none of the common indicators of serious illness. No pain, no weakness, no dramatic changes in weight.

Yes, I felt an unyielding pea-shaped thing just under the skin of my right breast near my armpit, and yes, I needed a biopsy. Doctors gave me reassurances I hadn’t asked for. “Don’t worry, you’re so young, it will be nothing, but we have to cut it out and analyze it.” In my innocence and ignorance, I accepted their optimism as fact. Cancer was not in my frame of reference; there was no cancer history in my family.

But as I emerged from anesthesia, snuggled in a cocoon of morphine, tears were sliding down my placid face. Some part of my consciousness was grasping what the kindly surgeon had just said: “You have cancer. I am so sorry.”

I was in the kingdom.

One morning, well into the first year of my treatment, I found myself in pieces. Sitting hunched over on the edge of my extra-tall wooden bed, I was unable to propel myself off it to start my day. I was transfixed by the image that had come to me. I felt like a little, broken bird.

How alienating it was to feel so fragile, despite the tragedies and traumas I’d already navigated, including the death of my father by suicide when I was 4. What had defined me through all of these events was what I thought of as the only way to survive adversity: toughness. I could not allow what I thought of as my identity to be shattered. I shoved thoughts of weakness and “damaged goods” aside, berated myself for having them, got down off the bed, and stumbled back into the ring to fight another day.

But I was living a paradox. In the privacy of my own mind, I refused to accept that cancer was part of my identity, even though it was affecting it as surely as erosion transforms the landscape. Out in the world, I’d blurt out “I have cancer” because I took questions from acquaintances like “How are you, what’s new?” literally. Answering casual questions with the unvarnished truth wasn’t claiming cancer as my identity. It was an attempt to dismiss the magnitude of it, like saying “I have a cold.” I was still who I was before—a young person, still desperately seeking her true self, still striving to find her place in the world.

Meanwhile, deep in the treatment cycle, cancer had become my full-time job. The me I once knew was sinking deeper into the quicksand of doctor’s appointments, IV infusions, drug schedules, daily blasts of radiation and side-effects management. Certain “friends” had started to disappear, one had taken me on as a pet charity project, and I felt like a burden to those around me. I just wished I could go back to the way it was before. Of course, I refused to let cancer have anything to do with my identity.

With early-stage breast cancer, treatment has an end date, after which your mission is to pick up the pieces and somehow move forward. True to form, once I was done, I endeavored to slam the door on the past and put my life back together.

Then, in 2005, 11 years after the first diagnosis, my oncologist found a new lump in my other breast. Surgery and complications ensued. By the time I began the prescribed weeks of daily radiation, I was so diminished that, despite my willpower, I would collapse on my couch and lie there for hours after driving myself home from the appointments. In that forced, immobile solitude, I began to learn to surrender and accept what had happened to me.

Liza Bernstein speaks at a fundraising gala for Project Angel Food in 2009. Photo by Project Angel Food

ut it wasn’t until late 2009, three cycles into chemotherapy for my third cancer, that I fully grasped the relationship between my diagnoses and my identity. It was the day I found myself, for the first time in my life, feeling with certainty that I wanted to give up, that I could not go on.

I was slouched on the floor, resting my leaden head on the coffee table, when the capoeira instructor’s dismissive remarks came back to me, igniting a fuse of despair and fury. If cancer had happened to me three separate times, how could it not be a part of my identity? Why should I cower in the denial of my experience because it inconveniences others?

I sat up straight, despite the fatigue. And I vowed that if cancer had struck me three separate times, I would do no less than honor it and make meaning with it. I was going to use it for good.

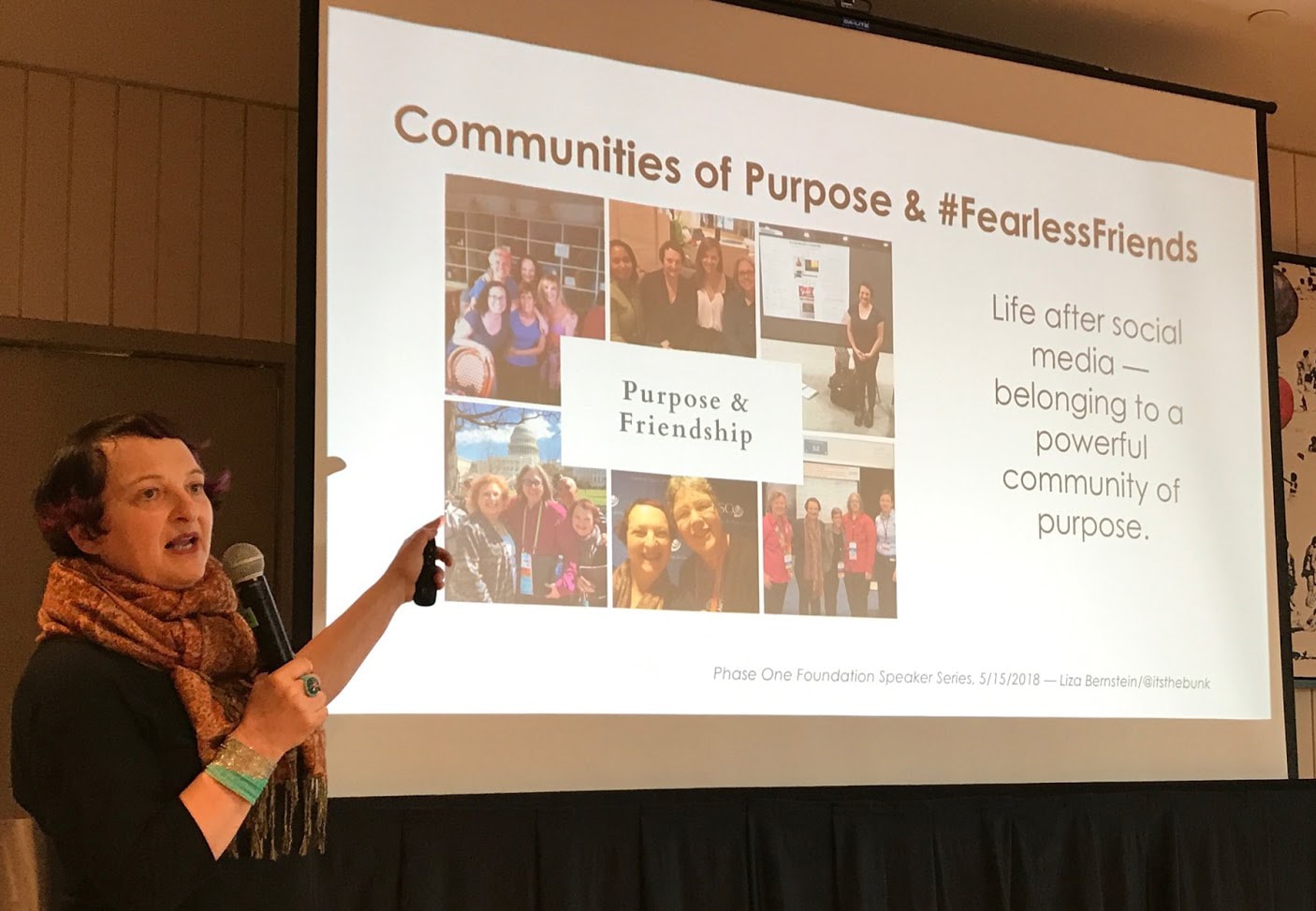

The fierceness of that oath propelled me forward, and I went on to become a patient advocate, channeling my love of learning and passion for understanding, connecting and collaborating across cultures and silos. Whether one-on-one, on Twitter, or giving presentations at conferences, I introduce people to relevant resources, organizations and evidence-based information; teach newly diagnosed patients to self-advocate and think critically; collect and share stories so people know they are not alone; continue to educate myself; and more. I’m in daily contact with a global network of cancer and health care stakeholders and continue to witness the impact an informed advocate can have, not only on individuals in her community, but on clinicians, researchers, industry and regulatory executives, health care designers and beyond.

In the years since I made that vow, I have managed to make a tense kind of peace with what happened to me. By finally claiming cancer as a part of my identity, I have found my place in the world.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.