Organizations Remain at Odds About Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines

A research letter published March 15 in JAMA Internal Medicine spotlights the controversy surrounding when to start screening for breast cancer and how often to perform these screenings. The research indicates that U.S. breast cancer centers are diverging in their recommendations from guidelines published by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society, which recommend starting screening as late as age 50 and 45, respectively, and waiting up to two years between mammograms. For the study, researchers reviewed the public websites of 606 breast cancer centers. Of the 431 centers that provided recommendations for when to start screening, 376 centers (87.2%) specified a starting age of 40, 35 centers (8.1%) recommended screenings start at 45 and 20 centers (4.6%) recommended screening start at age 50. In an accompanying editorial, JAMA Internal Medicine editors call out centers that benefit financially from increased screening volume. “Biennial mammography is preferred because it has benefits similar to those of annual screening but with fewer harms,” the editors note, as reported by Medpage Today. They conclude, “Breast cancer centers with clear financial benefits from increased mammography rates may wish to reconsider offering recommendations that create greater referral volume but conflict with unbiased evidence-based USPSTF guidelines and have the potential to increase harms among women.” The American College of Radiology fired back with a statement of its own, categorizing the assertions regarding financial motivations in the editorial and research letter as “outrageous and insulting.” The organization cites research and support for its own recommendations, which suggest women get annual mammograms starting at age 40, as well as similar recommendations from other national medical societies, including the American Society of Breast Surgeon.

Cancer Patients With Long-Lasting COVID-19 Could Play a Role in Evolution of Viral Variants

Patients whose cancer or treatment compromises their immune systems may require greater attention as discussion about COVID-19 vaccine prioritization continue. An article published March 15 in the New York Times describes a theory surrounding the evolution of viral variants: that people with weak immune systems who are infected with the virus may be more likely to develop viral populations with multiple mutations as their immune systems takes longer to fight off the virus. These people may also continue to shed the virus for long periods, leading to risk that they could transmit concerning variants to others. Adam Lauring, a virologist and infectious disease physician at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, told the New York Times that this group with weakened immune systems, such as cancer patients, should be among the first to receive vaccines. “We should give the best shot we can, both literally and figuratively, to protect this population,” he said.

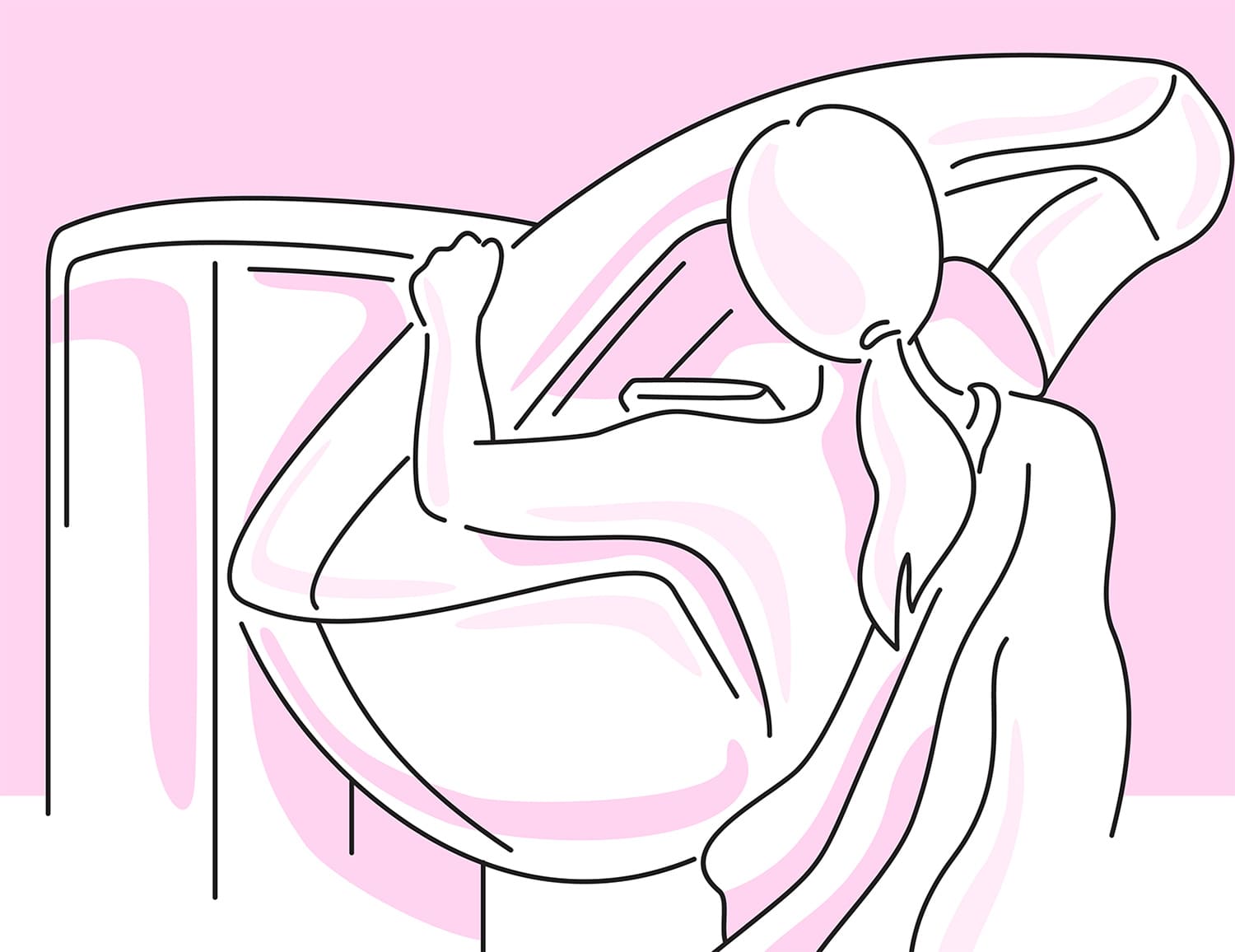

A Patient Ponders Modesty and the Indignity of the Paper Gown

Cancer and its treatment come with many indignities. Patients sit in a paper gown while talking to their white-coated oncologists as a matter of course. But Abigail Johnston, who has been living with metastatic breast cancer since 2017, questions whether donning the paper gown should be so routine. In a March 15 blog post, Johnston describes being alone in a room, in a gown she didn’t want to wear, as three radiology technicians ask her to completely disrobe for a scan she is getting. It’s necessary for her to be naked for the scan, but the indignity of the exchange sits with her long after the encounter. “It is overwhelming to have to give up one’s modesty, the trappings that make us individuals, the cloth that covers up our physical flaws, an armor of sorts,” she writes. She talks about that paper gown with a fellow cancer survivor, who makes it a rule that most of her encounters should occur while she is clothed, if possible. On the day of her scan, Johnston knew disrobing was essential, but she also wondered about other medical exchanges in common practice. “I get the necessity for easy access to the body parts that need to be scanned, and yet, otherwise, the insistence on wearing flimsy paper only amplifies the power that the medical system attempts to impose on the people who need said medical system to stay alive,” she writes.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.