MYRA CHRISTOPHER FELT THE MASS IN HER LOWER ABDOMEN prior to Thanksgiving 2010, but her schedule—as usual—was overflowing.

Besides a jammed work calendar, much of it to be spent on airplanes, the holidays were just around the corner: first Thanksgiving and then Christmas, then her older daughter’s 43rd birthday. Christopher, who relishes cooking up a storm with loved ones on any random night, particularly appreciates the festive pageantry of the holidays: the dishes, the linens, the flowers. “I love to wrap packages,” she says, chatting this spring in her Kansas City, Mo., office.

Detail minded, she’d marked Jan. 17, 2011, on her calendar as the day she would call her family doctor. She hadn’t mentioned the mass to Truman, her husband of more than 40 years. “He would have said, ‘We’re going to stop all of this nonsense,’ ” she acknowledges, now. But, as events unfolded, sudden and excruciating pain on the evening of Jan. 16 instead forced Christopher to the emergency room the next day. By that evening, doctors were rolling her into the operating room to remove a six-inch ovarian tumor.

By all accounts, Christopher has tackled her diagnosis and subsequent medical decisions with the level of intensity that she applies to her work at the Center for Practical Bioethics, which she helped launch in 1984. She served as its executive director and later as president for nearly three decades through 2011, and she continues her work there today. Since her mother’s death from cancer in 1978 at age 55, Christopher has championed the rights of patients to obtain better medical information and support as they wrestle with deciding which treatment paths are best for their personal situations and needs—whether those decisions involve an experimental protocol or a timely end-of-life discussion. She has scant patience, personally or professionally, for the sometimes convoluted and hierarchical medical system. “I won’t go to a doctor who won’t give me their cell phone number,” she says.

Treatment on Her Terms

That January, the 63-year-old expert in bioethics was the one lying in a hospital bed, reading reams of medical literature brought by friends and family. The physicians operating at Shawnee Mission Medical Center just outside of Kansas City had discovered a stage 1C tumor that had shifted painfully onto her spine. Sifting through the research studies, Christopher was determined not to be rushed as she weighed her treatment choices.

It was a rare type of ovarian cancer, called clear cell carcinoma, diagnosed in about 5 percent of women with ovarian cancer, according to a 2008 analysis of U.S. data. Although generally more aggressive than other ovarian cancers, clear cell carcinomas also tend to be caught a bit earlier, because they often grow into large masses that can be felt before metastasis occurs, says Michelle Dudzinski, Christopher’s gynecologic oncologist at Saint Luke’s Cancer Institute in Kansas City. (Nearly two-thirds of ovarian cancers aren’t diagnosed until they’ve metastasized beyond the lymph nodes; at that stage the five-year survival rate is 27 percent, according to National Cancer Institute data.)

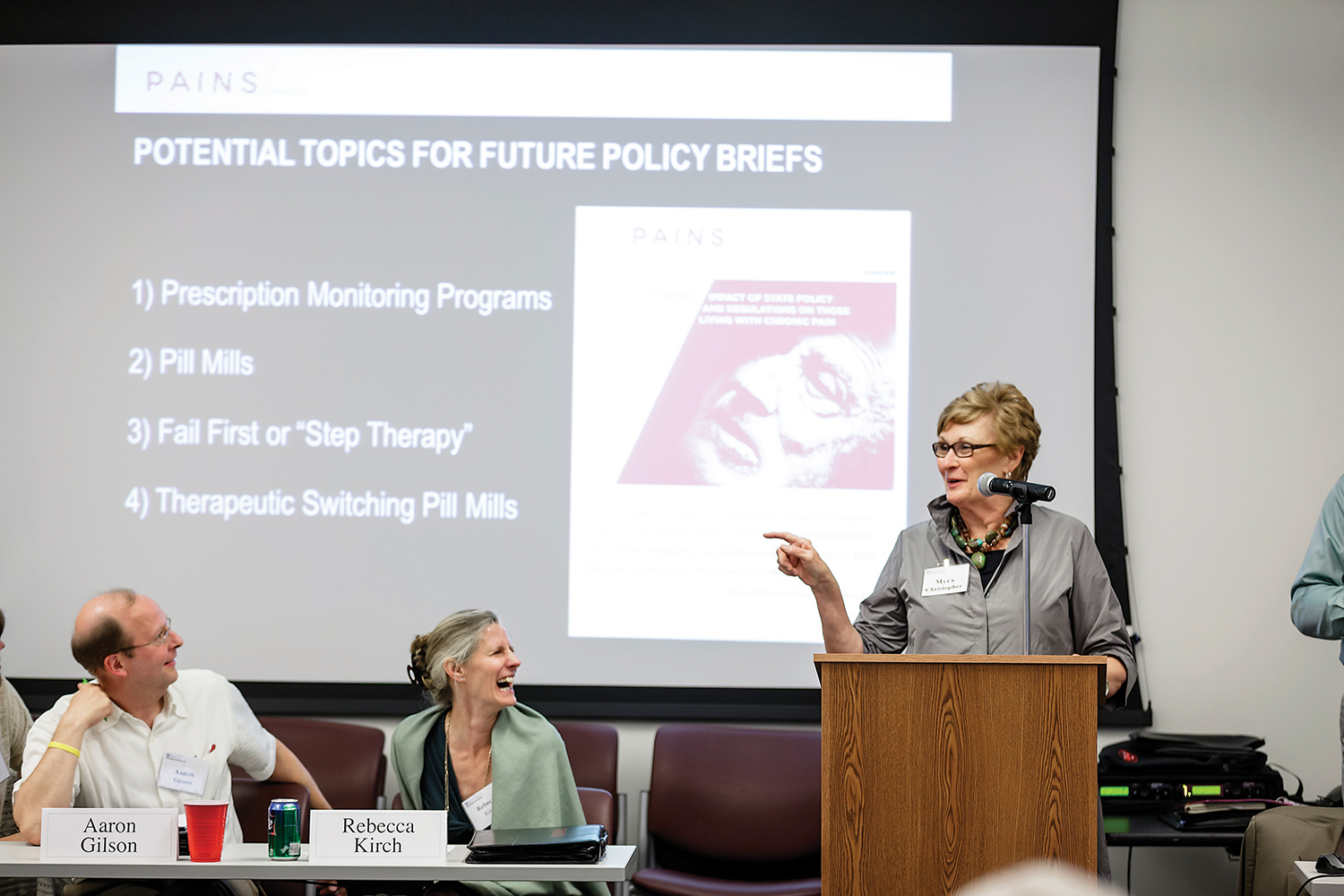

Myra Christopher speaks at a meeting on developing a national strategy on pain relief. Photo by Chad Jackson

Christopher’s tumor, which was attached to the endometrial wall, ruptured during surgery, filling the abdomen with potentially millions of malignant cells, Dudzinski says. It’s not an uncommon situation, says the physician, who took over Christopher’s care following surgery. Her abdomen was thoroughly rinsed with saline, Dudzinski says. “But you never know whether you got them all out or not.”

After mulling over the available research, Christopher agreed to chemotherapy, but decided early on that she did not want to get snagged by what she dubs “the treadmill” of repeated treatments. If the cancer recurred soon, within the first year after chemotherapy ended, she told Truman, she likely wouldn’t submit to additional cycles.

Christopher recounts a Kansas City Star obituary she stumbled across, profiling a woman with ovarian cancer who had lived eight years after being told she would survive only one. What struck Christopher was not the woman’s prolonged survival, but her protracted medical care. The woman had completed 90-plus chemotherapy cycles and at least half a dozen surgeries, recalls Christopher, who read the obituary to her husband.

“And I said, ‘That’s not me. This is not my life story. So, as we move through this, I just want you to remember this conversation.’ ”

She also spent considerable time choosing an oncologist, asking friends and family for suggestions before settling on Dudzinski. She preferred a female physician, and someone she “could be very direct with.” She also wanted a doctor who understood her twin passions: her work and her family, which includes two adult daughters and a grandson.

“Myra has real concerns,” her husband adds, “about physicians who don’t really tell the patients what’s wrong with them, who are not really honest with them about what their prognosis is and what their options are.”

Christopher had quickly dispatched the first oncologist who walked into her hospital room. “This kid came in,” she says. “And he said, ‘I’m your oncologist.’ And I said, ‘You know what, darling. I’m sure you’re an oncologist. But you’re not my oncologist.’ ”

Explore these resources for understanding options, planning treatment and care, and making wishes known.

Caring Conversations from the Center for Practical Bioethics is a family guide to advance care planning. The free guide includes a health care directive form and a durable power of attorney form.

Open to Options is a program of the Cancer Support Community that helps patients prepare for a doctor’s appointment during which they’ll be making decisions about treatment. Call 888-793-9355.

When Someone You Love Has Advanced Cancer: Support for Caregivers is a publication by the National Cancer Institute for people who care for individuals with advanced cancer. It includes information about hospice.

A Fighter For Patients’ Rights

Christopher’s interest in ethics, pain relief and end-of-life care dates back to her mother’s diagnosis with esophageal and stomach cancer in 1976. Christopher, just 28 at the time, first advocated for aggressive treatment, including an experimental surgery and chemotherapy. Two years later, after the cancer progressed, Christopher nursed her through her final weeks, at a time when hospice care was more concept than reality.

Afterward, the stay-at-home mother of two young children began taking classes in ethics and related subjects, including death and dying, at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. Soon she was studying under noted philosophy professor Hans Uffelmann. Six years later, when Uffelmann and two others founded what they were then calling the Midwest Bioethics Center, they recruited Christopher to be its first executive director.

Christopher opened the center out of a tiny office suite on the outskirts of Kansas City, initially its sole employee and unpaid for the first year. “She was a woman with a burr under her saddle after her mother died,” says Kansas City attorney Bill Colby, a friend who has known Christopher since the 1980s. Now called the Center for Practical Bioethics, the nonprofit organization employs roughly a dozen people at a downtown Kansas City office. The center’s staff members focus on real-life dilemmas—working on national initiatives, training more than 200 ethics committees around the country and mediating conflicts in the Kansas City area, sometimes standing at the patient’s bedside.

Christopher enjoys cooking with loved ones. Photo by Chad Jackson

Colby first called Christopher in 1987, when her center was still a fledgling organization, about a pro-bono case he had taken, one that would soon explode onto the national stage. It involved Nancy Cruzan, a young Missouri woman who was living in a vegetative state since a 1983 car accident. Christopher shared some articles with Colby about legal issues related to feeding tubes, sending them via taxi because the center didn’t have a fax machine, as Colby recalls it.

The family’s plea to remove Cruzan’s feeding tube, which wended its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, was ultimately rejected by the justices based on a lack of clear evidence regarding the young woman’s wishes. After the ruling, congressional leaders consulted the center during the drafting of the Patient Self-Determination Act. The 1990 law requires medical facilities to provide patients with information about advance directives.

The Cruzan case also represented a philosophical crossroads, according to Colby, who asked Christopher’s center to write an amicus—or “friend of the court”—brief supporting the Cruzan family. But the center decided to remain neutral—a stance Christopher says it’s strived to adhere to in the years since.

That neutrality has been called into question by a recent Senate Finance Committee inquiry. In May, the center was one of seven medical organizations contacted by the committee, which requested details about its funding ties to manufacturers of opioid-based medications. (One of the organizations contacted, the American Pain Foundation (APF), received 90 percent of its 2010 funding from the drug and medical-device industry, according to a late 2011 investigation by the news group ProPublica. The APF, an advocacy group for pain patients, shut down the same month the letters were sent.)

Officials at the Center for Practical Bioethics, which responded to the finance committee in June, state that on average, 10.3 percent of the center’s annual operating dollars dating back to 1996 have been contributed by pharmaceutical or medical device companies. In addition, the position that Christopher currently holds, the Kathleen M. Foley Chair for Pain and Palliative Care, is one of several endowed chairs. It was created by a $1.5 million donation from Purdue Pharma, which manufactures pain medications, including OxyContin.

For Christopher, who by late October had heard nothing further from the committee, the inquiry struck a deep nerve. “One of our core values is to be unfettered by special interest,” she says. “The first thing I say to corporate folks is, ‘I cannot offer you anything in return for your contribution other than the good work that we do.’ ”

The Problem of Pain

Back in March, Christopher was leading one of those good works: a Kansas City gathering of more than 40 doctors and others interested in developing a local initiative to improve pain relief, part of her latest efforts to tackle pain with a multifaceted approach, involving physical therapy and psychological support, along with medications.

It had been more than a year since Christopher’s diagnosis. Her hair had grown back, curlier than before, and was colored a sassy red. Standing nearly 5 feet 9 inches, her gaze steady behind dark-rimmed glasses, she assumed a commanding presence.

Christopher loves to tell stories, and her language can be colorful, irreverent about herself and others. But she doesn’t dominate a conversation, says Richard Payne, a pain medicine specialist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., and a colleague. “So when she talks,” he says, “people listen.” Payne served with Christopher on an Institute of Medicine committee that released the 2011 report Relieving Pain in America, which outlined a need for more effective prevention and relief for the estimated 100 million Americans living with chronic pain.

Since Christopher’s cancer diagnosis, pain has been not just a professional issue, but a personal one. She recalls the pain from both her eight-inch abdominal incision and the post-surgical tube. “I was so glad to get that tube out that they could have cut my arm off and I wouldn’t have cared,” she says.

Her subsequent chemotherapy regimen consumed the first half of 2011, with six cycles total of carboplatin and Taxol (paclitaxel), administered every three weeks. Her memories of the side effects remain vivid: the head-constricting sensation of her first wig and the sores and metallic taste that chemotherapy left in her mouth. Only coffee ice cream “by the pint” appealed.

But by last summer, she had completed her first year in remission. And by late October, regular CT scans and blood work hadn’t identified any signs of recurrence, she says.

Christopher spends time with her family. Photo by Chad Jackson

Christopher insists that she doesn’t obsess about each checkup, but time clearly weighs on her mind. She frequently states that she has at least “five good years” to complete her pain-related work. At one point, sitting in her Kansas City office, she chokes up as she discusses her desire to watch her 15-year-old grandson, George, graduate and head off to college.

Still, she remains wary of the treatment treadmill. When she developed nerve-wracking abdominal bloating three months after chemotherapy ended—it turned out to be a flare-up of her ulcerative colitis—Christopher was blunt with her husband. “I said, ‘If the cancer is back, I’m not going to do anything more.’ ”

For clear cell carcinoma, the survival data are limited, given its rarity, says Dudzinski. But Christopher’s odds from the start were good, her oncologist says: at least 75 percent for five-year survival. With each passing year, her risk of recurrence recedes. Of those cancers that do return, 85 percent appear within the first three years.

Even now, Christopher insists that she would weigh the toxic side effects against the potential benefits if a scan showed cancer again. “The chemo just kicks you in the teeth,” she says. “You’re down and a big pain in the behind to yourself and everyone else for about six months. And then you maybe get six more good months?”

Her similarly plain-spoken oncologist doesn’t agree. If the cancer responded well the first time to chemotherapy, as it did with Christopher, the odds are overwhelming that it would again, Dudzinski says. In her nearly 30 years of caring for patients, she says, most opt for chemo again.

Truman’s response: “She may be wrong in Myra’s case.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.