AS SHE ROSE from a small-town girl to a Hollywood star, Rosemary Clooney, affectionately referred to by family and friends as Rosie, became one of America’s most beloved singers. Her path included a complicated childhood, wealth and fame, a troubled marriage and, later, mental illness. But throughout, the one constant in her life was singing. She released almost 70 albums before her death in 2002, when she died of non–small cell lung cancer at age 74.

In the early days of her career in the 1950s, Clooney was known for performing novelty songs like ‘A’ You’re Adorable. As she got older, she would sing sensitive tunes about love and pain, like How Long Has This Been Going On? and Everything Happens to Me. A critic for the San Francisco Examiner wrote after a 1976 comeback performance, “She opens her mouth, gives a little smile, half-closes her eyes and vocally fondles the lyrics of [the songs]. And subsequently, listeners wonder why these songs never sounded so good before.”

A Difficult Start

Born in Maysville, Kentucky, on May 23, 1928, Clooney found success, but it was hard-won. Her father, Andy, was an alcoholic who struggled to make a living. Her mother, Frances, traveled a great deal for her dress business. In 1941, Clooney, her brother, Nick, and sister, Betty, moved with their parents—who had already divorced—to Cincinnati after Andy got a job at a defense plant. That same year, Frances remarried and moved to California with Nick, leaving Rosemary, then 13, and her sister, Betty, then 10, behind with their father. In 1945, her father went out one night with friends to celebrate the end of World War II. He never came back.

Clooney, 17, and her sister, 14, found themselves in a dire situation. They collected soda bottles and used what little money they had to buy lunch at school. The rent was overdue, the phone disconnected and the utilities about to be turned off when their luck changed. The teenagers, who had grown up performing at political rallies for their grandfather, the mayor of Maysville, won a singing competition at WLW, a local radio station. The station hired them for a regular late-night spot, with each sister earning $20 a week.

Their live performances on the radio led to a traveling gig with Tony Pastor and His Orchestra in 1946. Already known for novelty songs, Pastor thrived with the Clooney sisters on board. Accompanied by an uncle who served as a chaperone, the pair traveled around the country with the orchestra for three years. Betty decided to return to Cincinnati, but Rosemary wanted more. In 1949, at age 21, she moved to New York City for a shot at fame as a recording star and an actress in movies and on television.

Rosemary Clooney, second from right, appeared in the 1954 film White Christmas with, from left, Bing Crosby, Vera-Ellen and Danny Kaye. Photo by Silver Screen Collection / Getty Images

Clooney’s arrival in New York coincided with the heyday of “girl singers,” who often accompanied orchestras. Many became recording stars in their own right. In 1949, Clooney obtained a contract with Columbia Records. She was assigned to work with recording executive and bandleader Mitch Miller, who pushed her to record a quirky song called Come On-a My House. Later in life, Clooney recalled, “I think it was a musically snobbish time in my life. I really hated that song, and my first impression was, what a cheap way to get people’s attention.” After Miller threatened to fire her if she didn’t record the song, Clooney complied, and much to her surprise, it became an instant hit—and made her a star.

Clooney’s fame continued to grow through the 1950s with songs like Tenderly, Botch-a-Me, Hey There and This Ole House, culminating in 1954 with her critically acclaimed performance as Betty in the film White Christmas, with Bing Crosby.

CT scans recommended for older heavy smokers.

Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography (CT) is now recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for individuals between the ages of 55 and 80 who currently are or have been heavy smokers. Heavy smoking is defined as smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for 30 years or two packs daily for 15 years.

The guidelines were developed as a result of the National Lung Screening Trial that found annual screening with low-dose CT reduced lung cancer deaths among active and former heavy smokers by 20 percent in comparison with a standard chest X-ray.

All screening tests have risks and benefits. The risks associated with lung cancer screening include:

- false-positive results that can lead to unnecessary tests and surgeries;

- the finding of tumors that would never have caused a problem; and

- radiation exposure that increases cancer risk.

Life in the Spotlight

In 1952, while filming Here Come the Girls and Red Garters, Clooney began a romance with her dance instructor Dante DiPaolo. Unbeknownst to DiPaolo, she was also involved with the Academy Award-winning actor José Ferrer. In 1953, she made her choice. She left DiPaolo and married Ferrer. They settled in Beverly Hills and had five children.

Shortly after their first child was born in 1955, Clooney began her star turn on The Rosemary Clooney Show. The syndicated variety show ran for a year on more than 100 television stations and counted Johnny Mercer, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Cesar Romero among its guests. In 1956, NBC took over the show, changing its name to The Lux Show Starring Rosemary Clooney. It was broadcast live through 1958.

Balancing motherhood and work was a struggle. “Life with Mama was a mixed bag,” says Monsita Ferrer, Clooney’s daughter, who still lives near her childhood home in Beverly Hills. “She was on the road a lot, so our grandmother [Frances] moved in with us and kept the house going. It turned out well, though, because they got to know each other again and rebuilt their relationship, which was important to both of them.”

By contrast, Clooney’s relationship with Ferrer was troubled. They divorced in 1962, remarried in 1964, and divorced again in 1967. Around the same time, Clooney developed an addiction to tranquilizers and a drinking problem, and her behavior became increasingly erratic. “Nobody could approach me,” she wrote in her 1977 autobiography, This for Remembrance. “I was like a hand grenade with the pin pulled. Nobody could tell whether it was a dud or the real thing, because one minute I could be completely sweet and kind, the next, a raving monster.”

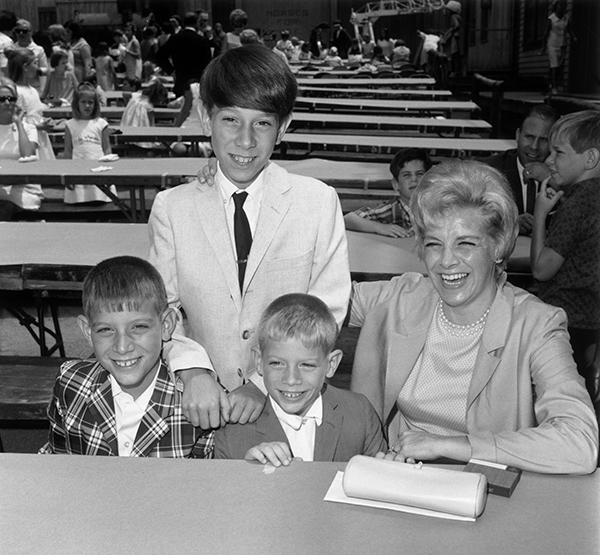

Rosemary Clooney appears with three of her children at a party in 1966. Photo by Max B. Miller / Fotos International / Getty Images

Hard-won Recovery

On June 5, 1968, Clooney was just yards away from her good friend Robert F. Kennedy when he was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He died the next day. Clooney had campaigned for Kennedy, who had just won the California Democratic presidential primary.

A month later, she walked offstage during a performance in Reno, Nevada. Shortly thereafter, she was diagnosed with and began treatment for bipolar disorder. Even during her emotional ups and downs, she worked. “Mama would take whatever job she could,” says Monsita Ferrer. “She played at Holiday Inns and appeared in Coronet paper towel commercials on television.”

In 1975, her good friend Bing Crosby invited her to join him for his 50th anniversary tour. A year later, she signed a contract with record company Concord Jazz. The 1970s were also when she reconnected with her old flame DiPaolo, whom she met by chance in 1973 and went on to marry in 1997. For Ferrer, her mother’s shining moment came in 1991, when she performed at Carnegie Hall in a New York City concert showcasing many of her hits, with singer Linda Ronstadt as her guest star. “She [had been] down, but she clawed her way back up,” says Ferrer. “I’ve always been so proud of her courage.”

A long-time smoker, Clooney was hospitalized in 1996 with acute respiratory failure. At that time, her doctors advised her to quit smoking, but Clooney struggled with her addiction. “Mama called me from the hospital and asked me to bring her cigarettes,” Ferrer remembers. “It was so hard for her to stop, though she finally did.”

Toward the end of 2001, Clooney was on the road performing when she began to find it hard to breathe. By the time she arrived home in Beverly Hills a few days before Christmas, she was exhausted. “She could hardly get up the stairs,” says Ferrer. “After two steps, she would have to stop and rest.” Less than a month later, Clooney was diagnosed with stage IIIA non–small cell lung cancer. She died six months later, on June 29, 2002, at her home in Beverly Hills with her family beside her. She was 74.

Rosemary Clooney is shown with singer Diana Krall at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, where Clooney received the Society of Singers’ Ella Lifetime Achievement Award in October 1998. Photo by L. Cohen / Getty Images

Treatment Then and Now

Clooney was one of about 169,400 Americans diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002 and among the approximately 154,900 people who died that year from the disease. The American Cancer Society (ACS) estimates there will be 224,210 lung cancer diagnoses and 159,260 deaths in 2014. Lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer death in this country and in 2014 will account for an estimated 27 percent of cancer fatalities. However, lung cancer incidence rates have declined by 2.6 percent in men and 1.1 percent in women each year between 2005 and 2009—a trend attributed to the success of anti-smoking campaigns.

Knowledge about lung cancer and its treatment has expanded since 2002, says Eric Edell, a pulmonologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who treated Clooney. Like most lung cancer patients then, Clooney underwent surgery to remove “as much of the tumor as possible and determine how far it had spread to her lymph nodes or other organs,” says Edell. “Chemotherapy and radiation were considered, but she was afraid of those treatments.” As it turned out, the question was moot. She never fully recovered from her surgery to undergo additional therapies.

Today, tools such as endobronchial ultrasound, available since the 1990s but perfected in the mid-2000s, allow doctors to look inside the lung, and, if suspicious areas are detected, to take a small sample for a biopsy before performing surgery. This procedure is less invasive than more traditional biopsies and allows for more accurate analysis of the tumor and surrounding lymph nodes, resulting in better staging of the disease.

There is also now a recommended screening test for heavy smokers to detect lung cancer earlier. Only 15 percent of lung cancers are detected at an early stage, according to the ACS.

Non–small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 84 percent of lung cancer diagnoses. A growing number of these lung cancer patients have new treatment options, as scientists continue to develop drugs that target some of the mutations that drive tumor growth.

For example, about 10 percent of people diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer have tumors with certain types of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. A targeted therapy called Tarceva (erlotinib) can block the EGFR signal, interfering with the mutation’s ability to make tumors grow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved Tarceva in 2004 for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer who were not responding to chemotherapy. Last year, the FDA also approved the drug as initial treatment for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer, after a study showed Tarceva increased median overall survival in patients with metastatic lung cancer by more than three months, from 19.5 to 22.9 months, when compared with chemotherapy. In addition, 65 percent of patients with this mutation responded, at least initially, in the Tarceva arm, compared with 16 percent in the chemotherapy group.

In the last three years, the FDA has approved two other targeted therapies, Xalkori (crizotinib) and Zykadia (ceritinib), for non–small cell lung cancer tumors that have an abnormal anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene. About 5 percent of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer have tumors that test positive for the ALK mutation. In one study that led the FDA to grant regular approval of Xalkori for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer, previously treated patients were divided into two groups: chemotherapy and Xalkori. The cancer stopped progressing for a median of 7.7 months in the Xalkori arm, compared with three months in the chemotherapy group. Zykadia, which was FDA-approved in April 2014, provides another treatment avenue if patients with non–small cell lung cancer stop responding to Xalkori.

In most cases, targeted treatments stop working. “Think of the mutation as signals from an antenna, broadcasting messages to keep the tumor growing,” says Lecia Sequist, an oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “The inhibitor turns off the antenna so it can’t transmit messages. But then the antenna changes its shape, causing the inhibitor to stop working.”

Once the tumor progresses, oncologists can do a second biopsy to see if the tumor has acquired a new mutation that could make patients candidates for another targeted therapy, says David Johnson, an oncologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Researchers hope that further genetic analysis might lead to more ways to overcome drug resistance and better combination therapies. For example, research analyzing the KRAS mutation, which is found in 25 percent of non–small cell lung cancer tumors, is ongoing, though scientists have yet to discover effective therapies for this common lung cancer mutation.

Immunotherapies—treatments that help the immune system fight cancer cells—are also being tested for lung cancer in clinical trials. For example, checkpoint inhibitors, drugs that target specific molecules on immune cells to release the brakes on the patient’s existing immune response, are currently in phase III clinical trials for non–small cell lung cancer. (See “Unleashing the Immune System” from the spring 2014 issue of Cancer Today for more information on immunotherapy.) Several other immunotherapies, including therapeutic vaccines, are also being tested in clinical trials, as well.

A Lifetime of Achievement

A few months before Clooney died, her son Miguel Ferrer accepted Clooney’s Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award while his mother was recovering from lung surgery. Clooney also received an Emmy nomination, the third of her career, in 1994 for her appearance in an episode of the TV series ER in which she played an Alzheimer’s patient who could only communicate by singing—acting alongside her now-famous nephew George Clooney.

Rosemary Clooney’s dream was to continue working her whole life—and she achieved it. As she told an interviewer from Lear’s magazine in the mid-1970s: “I’ll keep working as long as I live because singing has taken on the feeling of joy that I had when I started, when my only responsibility was to sing well. It’s even better now … I can even pick the songs. The arranger says to me, ‘How do you want it? How do you see it?’ Nobody ever asked me that before.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.