MANY WRITERS ACHIEVE FAME. John Updike attained something more: As a novelist, short story writer, poet and critic, he conquered the literary world, becoming one of only three authors to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction not once, but twice.

Updike’s eye for detail emerged during his childhood in Shillington, Pennsylvania, a small town outside of Reading, itself about an hour’s drive from Philadelphia. Shillington was not a place of prominence. It mostly knew the day-to-day, the conversations that play out at work, with family, or with oneself. There, Updike found an emotional frontier that he shaped into stories that spoke to millions around the world. Like many fiction writers, Updike put himself on the page. But probably few have written a memoir that includes footnotes linking the real events to his portrayal of them in his writing.

Not only did he write in many forms, Updike wrote all the time, producing on average a book a year. That didn’t change after he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008. He spent the months before he died writing poems on facing mortality, many of which were published in his collection Endpoint and Other Poems.

Updike died on January 27, 2009. The following day, his poem “Requiem” ran as an op-ed in the New York Times. It was pure Updike: His own life, retold.

It came to me the other day:

Were I to die, no one would say,

“Oh, what a shame! So young, so full

Of promise — depths unplumbable!”

Instead, a shrug and tearless eyes

Will greet my overdue demise;

The wide response will be, I know,

“I thought he died a while ago.”

For life’s a shabby subterfuge,

And death is real, and dark, and huge.

The shock of it will register

Nowhere but where it will occur.

The Hatching of a Writer

John Hoyer Updike was born March 18, 1932. An only child, Updike spent his first 13 years in Shillington, living in a two-story white brick house that his maternal grandfather purchased in 1922, for $8,000. His father, Wesley Russell Updike, was a high school teacher. His mother, Linda, longed to be a published writer. In essays and poems, Updike described both the sound of her typewriter keys and her disappointment when the manuscripts she had sent off in large brown envelopes were returned, unaccepted.

The family planted a dogwood tree on the side of their house a year after Updike was born. In Updike’s eyes, “The tree was my shadow, and had it died, … I would have felt that a blessing like the blessing of light had been withdrawn from my life.”

In October 1945, Updike’s grandparents sold their Shillington home, the place, Updike later said, where his “artistic eggs were hatched.” His new home—the family farmhouse where his mother had been raised in the nearby village of Plowville—wasn’t far. Yet the move marked a deep loss, which he explored 20 years later in his first autobiographical essay, “The Dogwood Tree: A Boyhood.”

As his father’s car pulled away from the curb, Updike wrote later, “I twisted and watched our house recede through the rear window. Moonlight momentarily caught in an upper pane. … The silhouette of the dogwood tree stood confused. … I turned away before it would have disappeared from sight; and so it is that my shadow has always remained in one place.”

Learn more about targeted drugs and immunotherapies.

Targeted Therapies

Scientists have identified specific mutations in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that can be blocked with targeted cancer therapies. Patients with NSCLC should have their tumor tested for these biomarkers:

- EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) mutation: Patients whose tumors have specific types of EGFR mutations can be treated with Tarceva (erlotinib), Iressa (gefitinib) or Gilotrif (afatinib).

- KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) mutation: Tumors that have this mutation are unlikely to respond to Tarceva, Iressa or Gilotrif. Targeted therapies for KRAS mutations are being studied in clinical trials.

- ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase): Tumors with an ALK rearrangement can be treated with Xalkori (crizotinib) or Zykadia (ceritinib).

Immunotherapies

In 2015, two immunotherapies were approved for treating advanced NSCLC. These drugs help the immune system fight the cancer.

- Opdivo (nivolumab): Approved for patients whose cancer has progressed on or after platinum-based chemotherapy and, if eligible for, an EGFR or ALK inhibitor.

- Keytruda (pembrolizumab): Approved for patients who have a tumor that tests positive on the PD-L1 companion test, have tried a platinum-based chemotherapy and have been on an EGFR or ALK inhibitor.

More Information

Launching a Career

After graduating as co-valedictorian of the Shillington High School class of 1950, Updike moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend Harvard College, where he had received a scholarship. While in Cambridge, he met and married his first wife, Mary E. Pennington, an art student at nearby Radcliffe College.

In 1954, after completing their bachelor’s degrees, the couple moved to England, where Updike studied art at the University of Oxford. Their daughter Elizabeth was born in 1955. From there, they moved to New York City, where, at age 23, Updike began working as a staff writer at The New Yorker. Over the next 19 months, he published 80 pieces, solidifying what would become a five-decade-long relationship with the magazine.

Shortly after Mary gave birth to their son David in 1957, the young family left New York City for the small coastal town of Ipswich, Massachusetts, about 30 miles north of Boston. Updike wrote poetry and fiction. And his family grew, with Mary giving birth to their son Michael in 1959 and their daughter Miranda in 1960.

The Updikes left New York City because they needed more space. But in an essay reflecting back on his life, Updike noted another concern: his ongoing battle with psoriasis, an autoimmune disease he had inherited from his mother. Psoriasis’s “red spots, ripening into silvery scabs” had marred his body and his sense of self since kindergarten, he wrote in his memoir Self-Consciousness, making him “prisoner and victim of my skin.” He moved to Ipswich, he explained, because it had “one of the great beaches of the Northeast, in whose dunes I could, like a sin-soaked anchorite of old repairing to the desert, bake and cure myself.”

His “affliction,” he continued, also led him to choose a career as “a craftsman”—a writer—that would keep him out of the public eye. He married early because he couldn’t believe he had found a woman who “forgave me my skin.” He had children so young “to surround myself with people who did not have psoriasis.” He left New York City because, “my skin was bad in the urban shadows, and nothing, not even screwing a sunlamp bulb into the socket above my bathroom mirror, helped.”

The family settled into Ipswich. But in the early 1970s, Updike’s marriage unraveled, a topic he would fictionalize and painstakingly explore as he detailed the ending of Richard and Joan Maple’s marriage in The Maples Stories. The Updikes separated in 1974, and divorced two years later. In 1977, he married Martha Ruggles Bernhard. They ultimately made their home in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts, another small seaside town. But despite all the years he spent in Massachusetts, it was the geography and psychology of his childhood home in Pennsylvania that grounded Updike’s writing.

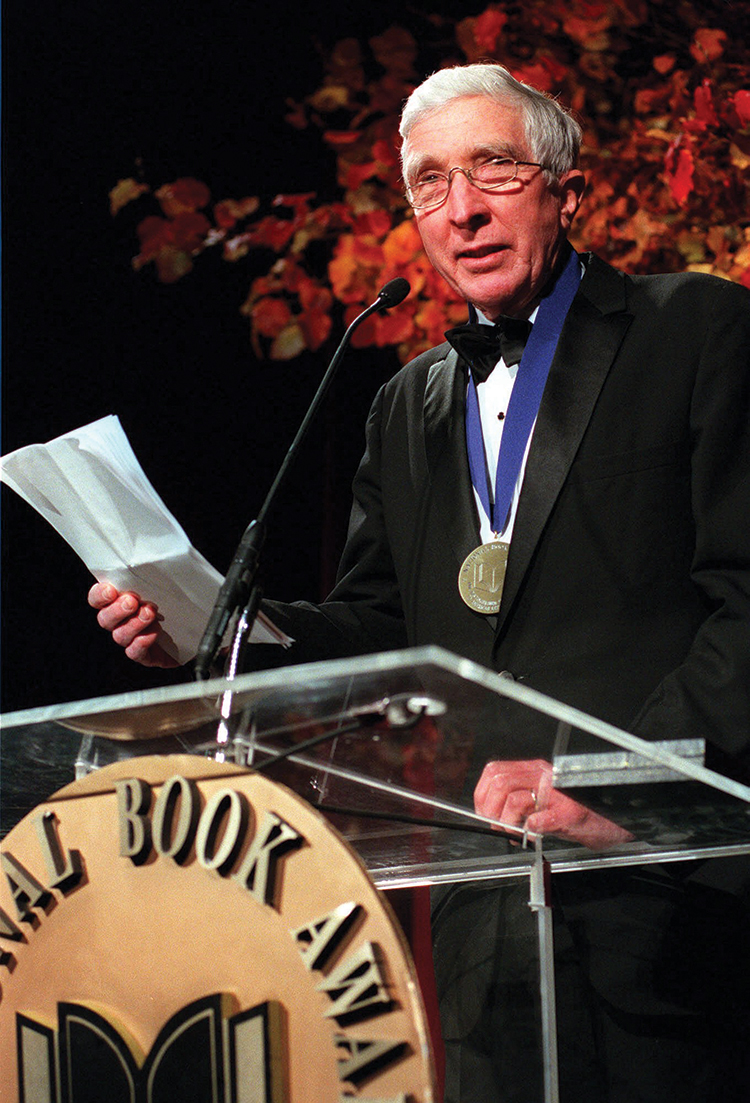

John Updike speaks during the National Book Awards in New York City in 1998. He received the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Photo © The Associated Press / Osamu Honda

Rabbit, Run

In 1960, Updike published Rabbit, Run, the first of four books featuring the character Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a man whose life peaked in high school as the star of the basketball team. When readers first meet Rabbit, he’s 26—yet already feeling a need to start over. He quits his job and leaves his pregnant wife and son in search of the “more” he believes America has promised.

Most readers, and critics, took to Updike’s fiction right away. But there were others who thought Updike was a stylish writer, yet had nothing to say. Updike believed they were gravely wrong. “I, who seemed to myself full of things to say, who had all of Shillington to say, Shillington and Pennsylvania and the whole mass of middling, hidden, troubled America to say,” he wrote in the essay “Getting the Words Out.” “What I doubted was not the grandeur and plentitude of my topic but my ability to find the words to express it.”

But express it he did. Updike dug into and used Shillington as the touchstone for the fictional universe of Olinger, the setting for many of his short stories. The nearby city of Reading was the inspiration for Brewer, the backdrop of Rabbit’s life.

Rabbit, Run was followed by Rabbit Redux (1971), Rabbit Is Rich (1981) and Rabbit at Rest (1990). The four books, carefully carved reflections of the political, economic and social changes taking place in the U.S., were a unique undertaking. “Certainly there were serialized characters in popular literature that people loved to read,” says James Plath, an English professor at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington and president of the John Updike Society, an organization focused on Updike’s life and work. “But in literature with a capital L, this was something new: to revisit the same character every 10 years and in the process give us a pretty good picture of life in small-town middle America. It stands alone in the canon of contemporary American fiction.”

Updike’s works received multiple honors. In 1964, he won the National Book Award for Fiction for The Centaur, an autobiographical novel that was a tribute to his father. For Rabbit Is Rich, Updike received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award. Nearly a decade later, he received his second Pulitzer Prize for Rabbit at Rest.

Updike received many other awards, including the 1989 National Medal of Arts and the 2003 National Humanities Medal. In addition, the National Endowment for the Humanities asked him to present the 2008 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, the U.S. government’s highest humanities honor. Even so, says his son Michael, he downplayed his fame. “He didn’t want to be a New York writer.”

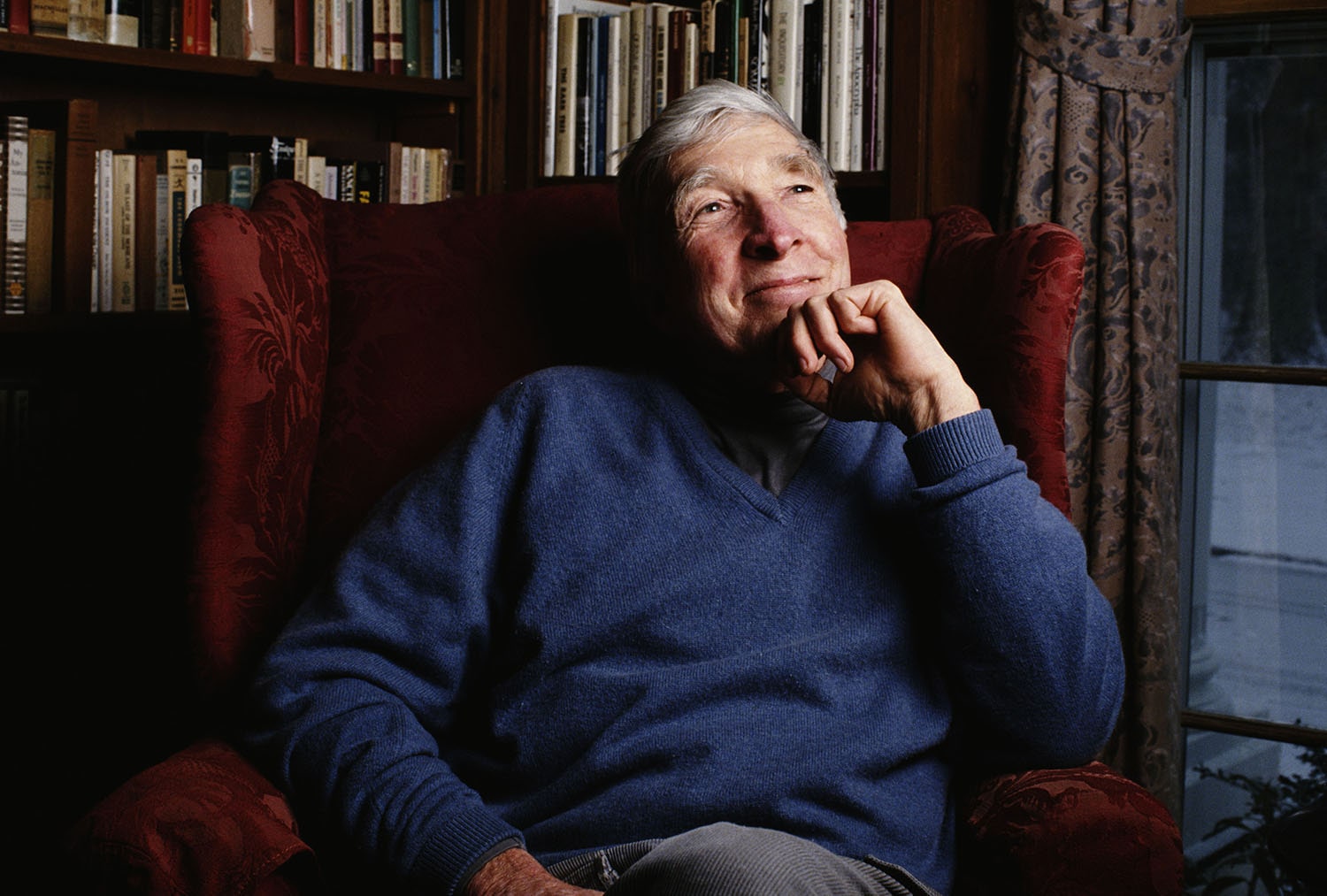

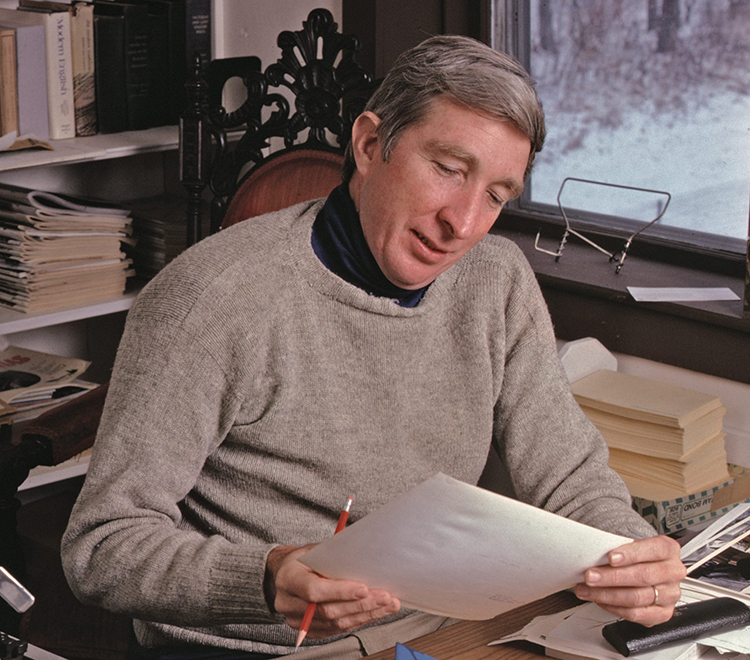

Pulitzer Prize-winning author John Updike works in his Massachusetts home. Photo © Getty Images / Jack Mitchell

Lung Cancer’s Toll

The American Cancer Society estimated that 221,200 women and men would be diagnosed with lung cancer in 2015, making it the second most common cancer in men, after prostate cancer, and the second most common cancer in women, after breast cancer. Although it was the second most common, representing about 13 percent of all cancer diagnoses, lung cancer was the top cancer killer. It was responsible for an estimated 158,040 deaths—or about 27 percent of all cancer deaths.

Lung cancer is divided into two main types: small cell, which makes up about 15 percent of all diagnoses and non–small cell, which accounts for about 85 percent.

It’s not widely known what type of lung cancer Updike had. It is known that he began to have some breathing problems in the summer of 2008. The initial diagnosis was bronchitis. When the cough didn’t clear, he was told it was pneumonia, a diagnosis he described as “oblong ghosts, one paler than the other on the doctor’s viewing screen” in a poem dated Nov. 6. Two weeks later, as Thanksgiving approached, Updike spent five days at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, undergoing the tests that led to his lung cancer diagnosis.

A misdiagnosis of pneumonia is “unfortunately, a common scenario,” says medical oncologist Joan Schiller, deputy director of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “Pneumonia is a heck of a lot more common than lung cancer, so it’s understandable that someone with a cough would be treated for pneumonia and then later find out it is lung cancer.”

When people die so quickly from cancer, it is often assumed the disease spread quickly. That can and does happen, but another common reason for a late lung cancer diagnosis is that it can be hard to know it’s there. “One reason is that the lungs don’t have a lot of nerves, so it doesn’t cause pain—and you can’t see it,” says Schiller. Still, she says, even for lung cancer, Updike’s two-month span from diagnosis to death was unusually quick.

Updike’s cancer was treated with chemotherapy. Were he diagnosed today, says Gregory A. Masters, a medical oncologist specializing in lung cancer at Christiana Care’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center in Newark, Delaware, he might have had more options.

“Instead of having everyone with stage IV lung cancer get the same chemotherapy,” says Masters, “we now see if the patient has one or more of the specific gene alterations that allow us to use a targeted therapy. If they do, we can give them a treatment that is more effective, less toxic and that will control the tumor for more time.” In addition, some patients with metastatic lung cancer whose tumors have stopped responding to chemotherapy may have the option of trying one of the recently approved immunotherapy drugs. However, it’s not known whether a patient like Updike, who had an autoimmune disease, could take an immunotherapy drug. “It’s unclear if it would be effective or what the side effects would be,” says Schiller. “These drugs have not been tested in these patients because there are concerns that you’d aggravate one of those other conditions.”

Treatments for early-stage cancers have improved as well. If lung cancer patients have a tumor that has not spread, they may be able to have video-assisted thoracic surgery, which uses a scope and camera and helps avoid “the huge 10-inch incision across the chest, which makes recovery easier and less painful,” says Masters.

Early-stage lung cancers can also now be treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). “With SBRT,” says Schiller, “doctors can focus the radiation beam more directly on the tumor, which results in minimal damage to surrounding normal tissue. This means patients can get higher doses of radiation than they would have been able to in the past.”

John Updike with his first wife, Mary, and their children. Photo © Getty Images / Truman Moore

A Life of Letters

In a poem dated Dec. 22, 2008, Updike wrote that a biopsy revealed his cancer was metastatic. He died approximately six weeks later, within 24 hours of being admitted to hospice. “It was a rapid decline,” says his son Michael, “but he was lucid and knew what was coming. He turned to his wife and said, ‘Are you ready for the leap?’ ”

Plath and other academic colleagues founded the John Updike Society four months after the author’s death. In August 2012, the society purchased Updike’s childhood home in Shillington. They plan to turn the house—where the dogwood tree still stands—into a museum and literary center.

Some of Updike’s ashes were placed in his mother’s family plot in Plowville. Michael, a slate artist, carved the memorial stone. “He was so fearful of death his whole life,” says Michael. “So we put on the stone an effigy that symbolizes his soul going to heaven”—his face, smiling, framed by wings. “We thought that would make him happy.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.