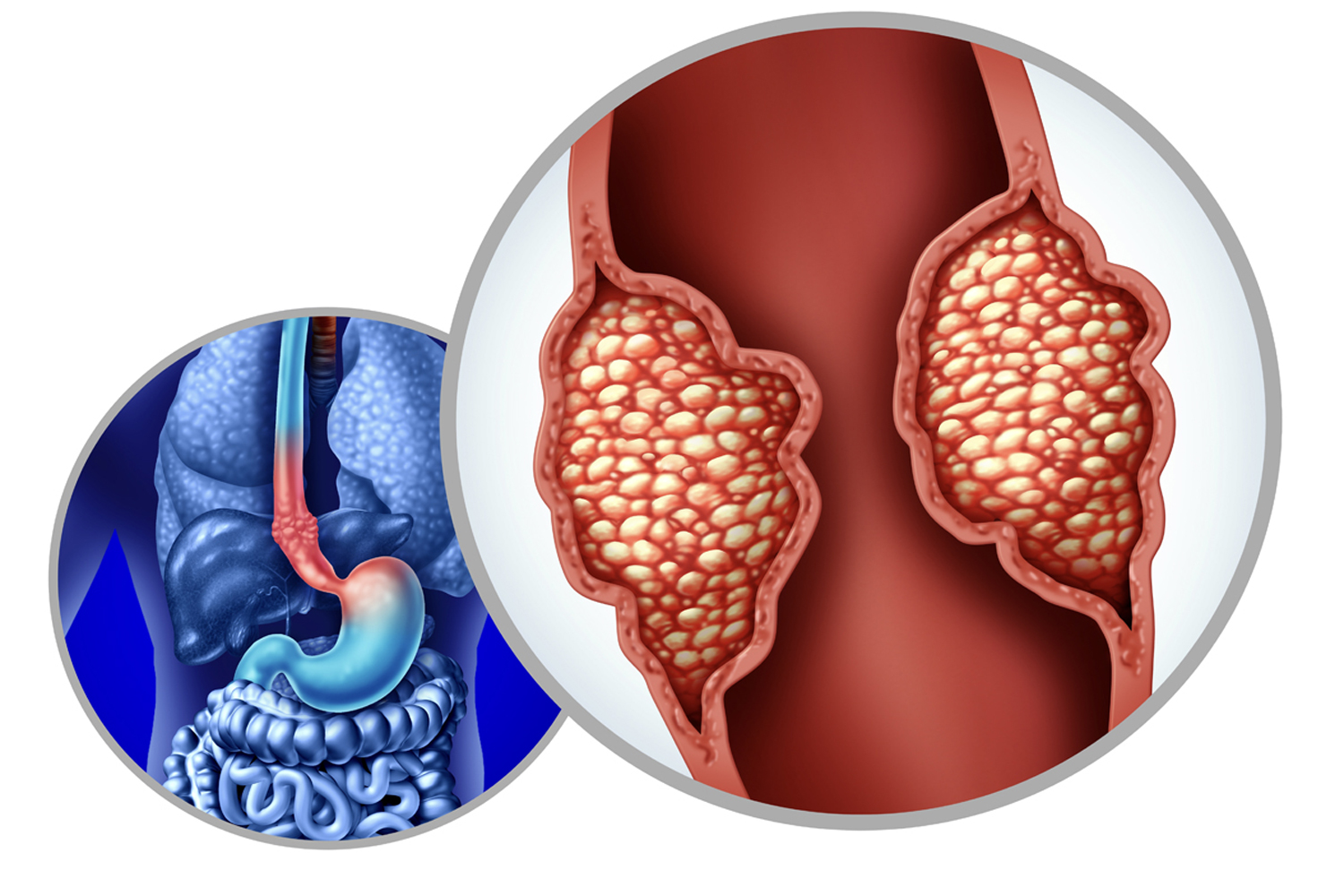

PEOPLE WITH ESOPHAGEAL CANCER who are eligible for surgery typically have the best chance for long-term survival. However, less than half of people diagnosed with the disease can undergo surgery because their tumor has already spread into nearby tissue.

A phase II clinical trial found the addition of immunotherapy to standard care could help shrink the tumor enough to make some patients eligible for surgery. In the study published Nov. 15, 2024, in Clinical Cancer Research, researchers followed 30 people who had esophageal squamous cell carcinoma that had spread to other nearby organs and lymph nodes but not to distant parts of the body. All participants, whose ages ranged from 42 to 73, had not yet received treatment and were not eligible for surgery. Participants started with the standard treatment of chemoradiation, which is chemotherapy and radiation given at the same time. Twenty-four patients had no tumor progression and then received the immunotherapy drug Tevimbra (tislelizumab) and additional chemotherapy. For 20 of those participants, the treatment shrank the tumor enough that they could have surgery. After surgery, 13 people had no signs of active cancer.

Adding immunotherapy before surgery can help the body’s immune system to better recognize and attack cancer cells, according to Yin Li, a thoracic surgeon at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences in Beijing and a senior author of the study. Among the 30 participants in the clinical trial, the one-year progression-free survival rate was 79.4%, while the typical rate for people with locally advanced disease who don’t qualify for surgery is 42%. One-year overall survival was 89.6% for all patients who participated in the trial. However, all 20 participants who received immunotherapy and had surgery were still alive a year later.

Some people had difficulty tolerating the combination of chemotherapy, radiation and immunotherapy. Eleven participants, or almost 37%, had severe or life-threatening adverse events, including low red and white blood cell counts, vomiting and esophagus irritation. Five people who received immunotherapy had immune-related lung inflammation. Li says these side effects are generally manageable with close monitoring and supportive care during treatment.

Even when surgery is successful, Li warns, the aggressive nature of esophageal cancer means microscopic cancer cells may have already spread elsewhere in the body, and the disease returns in up to half of people who have surgery. “Ongoing vigilance and follow-up care are essential for the early detection and management of any residual or recurrent disease,” Li says. To catch recurrences early, patients should get regular imaging scans after surgery, according to Li. To find microscopic cancer cells that scans could miss, his team is looking into using liquid biopsies, or blood tests, that detect circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), fragments of DNA that cancer cells shed into the bloodstream.

“Patients with particularly aggressive malignancies like esophageal cancer must consider both phases of cancer—the visible [tumor] and the microscopic cancer—when making treatment decisions,” says Daniel Boffa, a thoracic surgeon and chief of the division of thoracic surgery at Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut. While he’s encouraged by the results, Boffa, who was not involved in the study, says surgery works best when cancers are caught before they spread to other parts of the body, so patients should talk with their oncologists about the potential for residual disease.

On March 4, 2025, based on results from a separate clinical trial, the Food and Drug Administration approved Tevimbra, in combination with chemotherapy, as a first-line treatment for people with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma that expresses the protein PD-L1.

Li and his team will continue following the study participants to see five-year survival rates. They also plan to build upon this treatment strategy in a more extensive randomized controlled trial. Li says he’s hopeful that biomarkers, such as PD-L1 and ctDNA, found through tissue or liquid biopsies can help identify the people most likely to benefit from this approach and develop personalized treatment strategies for those with locally advanced esophageal cancer.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.