ONCOLOGIST SAM MAZJ was working at Adventist Health Feather River Hospital in Paradise, California, on Nov. 8, 2018, when a fast-moving wildfire forced the evacuation of everyone in the hospital. Mazj joined the effort to move 80 patients and 200 staff members from the danger zone, using ambulances, police cars and personal vehicles. The rapidly moving blaze—dubbed the Camp Fire—damaged the hospital and engulfed 18,000 other buildings in Paradise and nearby Concow, both communities in the Sierra Nevada foothills. At least 85 people died, making it the deadliest wildfire in California history.

The challenges didn’t end once the smoke cleared. Many people in the area were dealing with the loss of their homes and belongings, but cancer patients also lost the place where they received the care they needed, Mazj says. Many of his patients receiving chemotherapy or radiation had to drive an hour or more to unfamiliar clinics. Most had no access to their medical records, and their health care teams were scattered at different facilities. Others were not able to rely on families and friends, who were also affected in various ways by the devastation. “I think the aftermath was a much bigger impact as time went on,” Mazj says.

Catastrophe and Cancer: A Perfect Storm

Catastrophic events like wildfires, hurricanes and floods pose immediate danger to anyone in their path. As extreme weather events, from heat waves to storms, become more frequent due to climate change, researchers are studying how the planet’s health impacts human health.

Leticia Nogueira, an epidemiologist and the scientific director of health services research in the Surveillance and Health Equity Science department of the American Cancer Society (ACS), has seen the impact of catastrophic events firsthand. Working for the Texas State Department in Austin in 2017, she was part of the effort to coordinate response teams when Hurricane Harvey hit. While these events can have severe effects on anyone touched by them, the impact is heightened for cancer survivors, Nogueira says. “Their vulnerability to these environmental hazards is much higher than of people who don’t have any chronic health conditions.”

Nogueira and her colleagues published a paper in 2019 in JAMA that examined data from the National Cancer Database to measure the effects of hurricane disaster declarations on people who had locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer but weren’t candidates for surgery. Examining data from 2004 to 2014, the researchers compared patients treated with radiation in facilities affected by hurricanes to patients treated in the same facilities during normal times. Following hurricanes, people treated for non-small cell lung cancer had longer treatment durations, likely due to disruptions in care. Being treated during disaster declarations was also linked to worse overall survival. The longer that an area was declared a hurricane disaster site, the worse the patients fared.

Image by Benny Marty / Shutterstock.com

These poorer outcomes were likely not linked to treatment disruptions alone, Nogueira says. Patients may worry about loved ones, experience the stress of losing belongings or no longer have transportation access, which affects their ability to get to work and treatments, she says. They may also need to care for other family members with health conditions, which can lead to delaying their own treatments. “It’s all the things you have to deal with if you’re impacted,” Nogueria adds.

In the Wake of Climate-related Events

When Marisel Brignoni was first diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a rare type of blood cancer, in 2013, she received chemotherapy to destroy the cancer cells in her body and then had stem cells taken from her blood. The cells were then reinfused into her body. This procedure, called an autologous stem cell transplant, doesn’t cure multiple myeloma, but it can create long remission periods for those with the disease. She received her first transplant in June 2014 and had additional stem cells stored in a nearby American Red Cross blood bank in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for any possible recurrences.

In September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit Puerto Rico in quick succession and decimated the island’s infrastructure—destroying homes, causing power outages, disrupting cellphone service and blocking transportation routes. It wasn’t until 2019, when Brignoni needed another stem cell transplant, that she received bad news: The blood bank storing her stem cells had been without power in the hurricanes’ aftermath. The stem cells she banked for future cancer treatments were no longer viable.

Brignoni now works as a philanthropy adviser for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). She recalls how the 2017 hurricanes, which caused widespread damage across the island, left some stranded without clean water or power for weeks on end. “Nobody was prepared for Hurricane Maria,” says Brignoni, who had her stem cells harvested again for a second transplant in 2021 and now receives immunotherapy every two months. The 2017 hurricanes also created problems for cancer treatment elsewhere. A critical manufacturing company based in Puerto Rico had to stop production of saline fluids for IVs in the storms’ aftermath, creating a shortage that affected health care across the U.S.

These events, once isolated, have become more frequent and widespread as global temperatures continue to rise. In summer 2023, smoke from fires in Canada spread across the Midwest and Northeast of the United States. State health and environmental regulators from New York to Minnesota issued air quality alerts because of unhealthy amounts of fine particles in the air, which can settle inside the lungs and increase the risk of respiratory ailments.

Strategies that help one cope with a cancer diagnosis can also be an asset in weather-related disasters.

Worries about climate change can add to the anxiety one feels from a cancer diagnosis. In fact, the anxiety of both events can feel similar, says Beth Haase, a psychiatrist who studies the impact of climate change on mental health and is a founding member of the Climate Psychiatry Alliance. “Cancer is often frightening because people feel at the mercy of biological processes that have gone wrong and are beyond their control,” she says. With climate change, anxieties can also focus on the loss of control, she says, noting people may think, “At what point will we reach a point where everything is changing so fast that no recovery is possible?”

Both cancer care and our climate rely on fragile ecosystems. But those who have weathered the challenges of cancer and its treatment may be able to pull from the same coping mechanisms to get through climate-related anxiety. Strategies like seeing past their own experiences to help others can remove a sense of being alone, whether going through cancer treatment or getting through a weather-related disaster, says Haase, the medical director of outpatient behavioral health services at Carson Tahoe Regional Medical Center in Carson City, Nevada.

Sam Mazj, the medical director of the Enloe Health Regional Cancer Center in Chico, California, remains impressed by a similar spirit of selflessness in people he cared for after the Camp Fire. Most of his patients were able to find ways to continue their treatment and even to support others while dealing with the aftermath of the fire. “In reality, what amazes me is the resilience of the people,” he says.

In a May 2022 study in Lancet Planetary Health, researchers assessed wildfire exposure and cancer incidence for more than 2 million people in Canada through the Canadian Census Health and Environmental Cohort. Researchers found that those who were exposed to a wildfire within about 30 miles of home during a 10-year period had greater incidence of lung cancer and brain tumors than those who were farther away. And an international team studying cancer and wildfires in Brazil reported in a Sept. 19, 2022, article in PLOS Medicine that they found an association between exposure to small airborne particles called PM2.5, found in wildfire smoke, and an increased risk of death for patients with prostate, breast, gastrointestinal and other cancers.

Nogueira and her colleagues were interested in how proximity to wildfires might affect those who would be especially vulnerable, so they looked at people who had surgery for non-small cell lung cancer between 2004 and 2019 alongside NASA data that broke down wildfire events by ZIP code. “We know that lung cancer surgery is not easy to recover from. It has long-term consequences, even in your ability to move around and stay employed,” Nogueira says. “And we know it’s a very significant surgery.”

The study, published July 2023 in JAMA Oncology, found that those who were exposed to a wildfire in their ZIP code within three months of their surgery were less likely to be alive after a median of about 39 months than those who did not live near the site of a wildfire. Even people who had a wildfire in their ZIP code between seven months and a year after their surgeries still fared worse than those who did not live near wildfires.

The higher mortality rates in those living near wildfires might stem from a number of factors, including other stressors—the anxiety of witnessing a traumatic event, the need to evacuate, and the loss of social support, says Yang Liu, an environmental health scientist at Emory University in Atlanta and a co-author on the paper. More collaboration between fire- and climate-focused agencies and health care stakeholders could better support cancer patients through these challenges, Liu says.

Collaboration Efforts

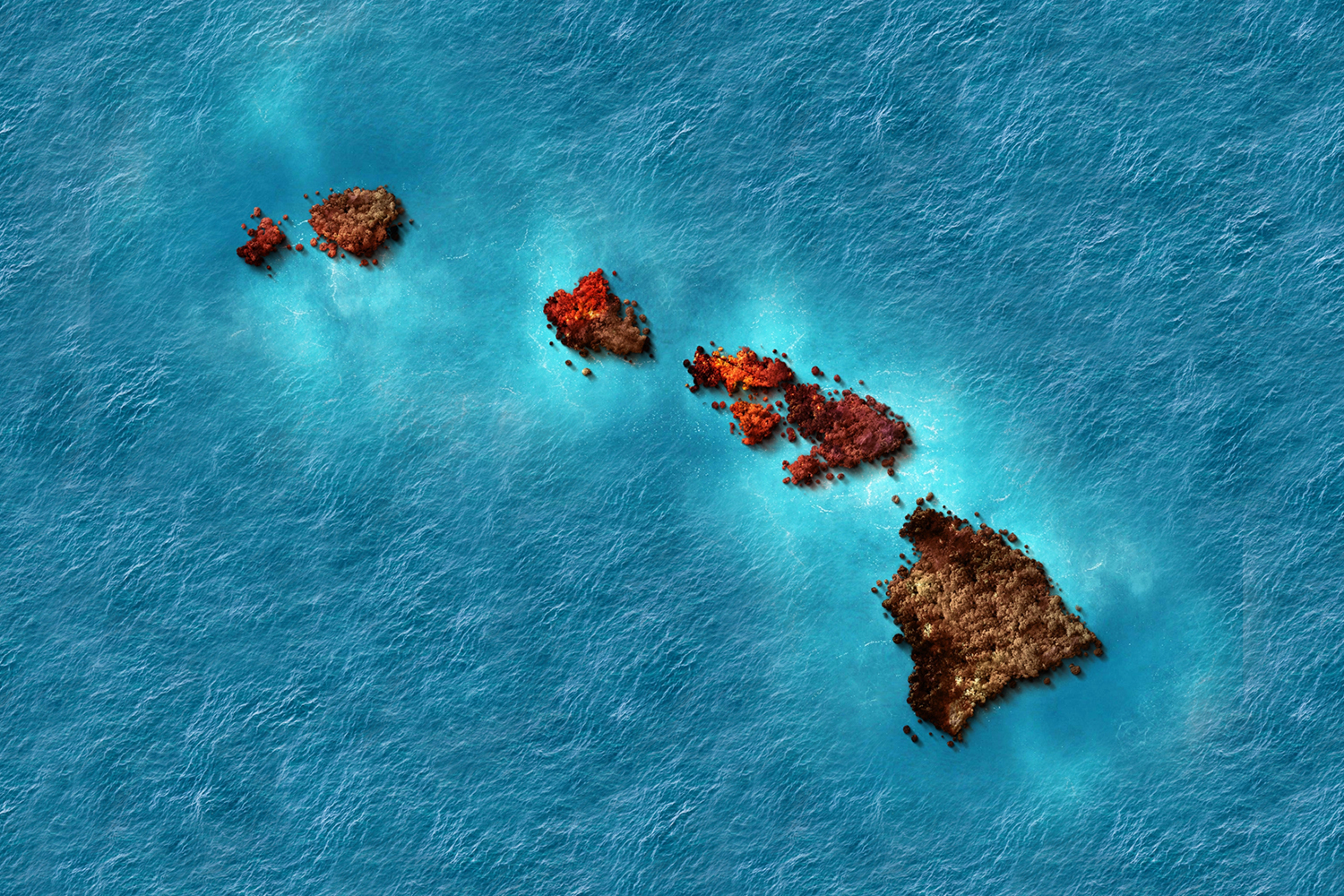

But the challenge of how to plan for climate-related weather events remains as disasters increase in number. The wildfire that hit Lahaina, a town on the Hawaiian island of Maui, on Aug. 8, 2023, killed 100 people and destroyed more than 2,000 homes. Many Lahaina residents whose houses were still standing had no access to clean water. People had to visit local water hubs to get water for drinking and cooking.

“If you’re a cancer patient and you’re exhausted, it’s hard to have to go out and get clean water,” says Laura Creider, executive director, Hawaii-Guam, for the ACS. Even now, many cancer patients in the area still live in temporary housing and need to move frequently from one location to another, she says.

Maui residents were already familiar with barriers to care, Creider says, with a shortage of oncologists and the need to fly to Oahu for treatment. “We just knew that the wildfires were only going to exacerbate preexisting cancer concerns that we were already facing,” Creider says.

In the aftermath of the wildfire, the ACS worked with local and national partners to help people with cancer receive treatment and provide lodging for those displaced from their homes in the ACS Hope Lodge in Honolulu.

Image by DOERS / Shutterstock.com

The need for coordinated and collaborative efforts is imperative. “We’re in the cancer business. What we do is not optional,” radiation oncologist Vivek Kavadi says.

Kavadi and his team at Texas Oncology-Sugar Land set up a command center to get patients safely to open clinics during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. As a result of their experiences, Texas Oncology made physical changes, including installing storm sewers, to their facilities to strengthen them against storms. To help radiation oncologists and cancer centers prepare for catastrophic events, Hiram Gay, a radiation oncologist at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues published a 2019 paper in Practical Radiation Oncology outlining lessons learned from the hurricanes in Puerto Rico. Maintaining care during a crisis is particularly important for patients with fast-growing cancers, Gay says. “Each day you miss, it’s a chance the cancer has to regrow.”

Shoring Up for the Storm

Medical organizations, too, are starting to assert the need to develop plans for climate resilience. Last June, the American Society of Radiation Oncology issued a climate change policy statement supporting climate-related education for patients and providers, along with better climate-focused strategies to protect patient health. In November 2023, the American Society of Clinical Oncology issued a policy statement on cancer and climate change encouraging efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of cancer care and to implement health care policies to address climate change. Addressing the dangers of climate change requires a systemic approach to provide care to people at their most vulnerable. “The last thing we want to do is put the burden on the patient,” Nogueira says.

But people with cancer and their families can take some proactive steps to ready themselves for an extreme weather event. Among the many challenges faced by cancer patients in the aftermath of the Camp Fire in California was the loss of physical medical records, says Mazj, now the medical director of Enloe Health Regional Cancer Center in Chico, California. He urges patients to keep paper copies and electronic backups of their medical records and to share their records and treatment plans with trusted caregivers or family members in case their own copies are lost or damaged. Medical records and prescriptions can also be kept with emergency kits that people can grab quickly if they need to evacuate.

Following Hurricane Maria, Martha Sanz, the manager of international patient services for Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, worked to arrange humanitarian flights, provide lodging and offer other services for patients who traveled from Puerto Rico to Florida to continue their care. She urges patients living in hurricane-prone areas to consider their course of action if a disaster strikes. “Have a plan, a hospital in mind in case your area is affected, and especially have your medical records,” she says. With no electricity and damaged cell towers, many patients had to drive several hours to find cell service to communicate with the team at Moffitt, and transferring records electronically with spotty signals was a challenge, she says. Sanz recommends that those in hurricane-prone areas get CDs of their scans, so that if they need to visit a new clinic after an emergency, they can have their records in hand.

Brignoni hopes to use her experiences with Hurricanes Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico to inform her efforts to develop better planning for patients undergoing critical cancer treatment during hurricane season. Through Dot4life, a foundation she started in 2015 to raise awareness of multiple myeloma, her goal is to work with doctors and patients in Puerto Rico and Florida to plan preemptive steps like moving patients out of affected areas a week before a hurricane is forecast so treatment isn’t interrupted. Recently Brignoni started conversations with health care providers, hospitals and pharmaceutical companies about the need for better patient support before, during and after natural disasters, “because climate change is continuing, and we don’t know when it’s going to be our next disaster,” she says.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.