BEHIND DISPARITIES in cancer risk and outcomes is a web of factors—income, environment, education, race and ethnicity, access to health care, and others—that underlies people’s experience and health throughout their lives. A session at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2024, held April 5 to 10 in San Diego, featured presentations on environment, health coverage and race that sought to explain what goes into disparities. (The AACR publishes Cancer Today.)

Recent research has moved into considering the immediate living conditions of people and the ways that can impact health, but according to presenter Scarlett Lin Gomez, an epidemiologist at University of California, San Diego, there are opportunities to look at wider, structural drivers that inform those conditions. “We need to recognize that there is actually a continuum of influences on health outcomes and cancer disparities,” Gomez said.

Gomez discussed findings that highlight the importance of factors outside the medical center in looking at the outcomes of cancer treatment. In one study she shared, the socioeconomic status of a patient’s neighborhood explained 7.6% of the breast cancer disparity and 7.1% of the prostate cancer disparity among racial and ethnic groups. Another found neighborhood socioeconomic status was a driving factor in breast cancer mortality even when considering individual social factors, including education.

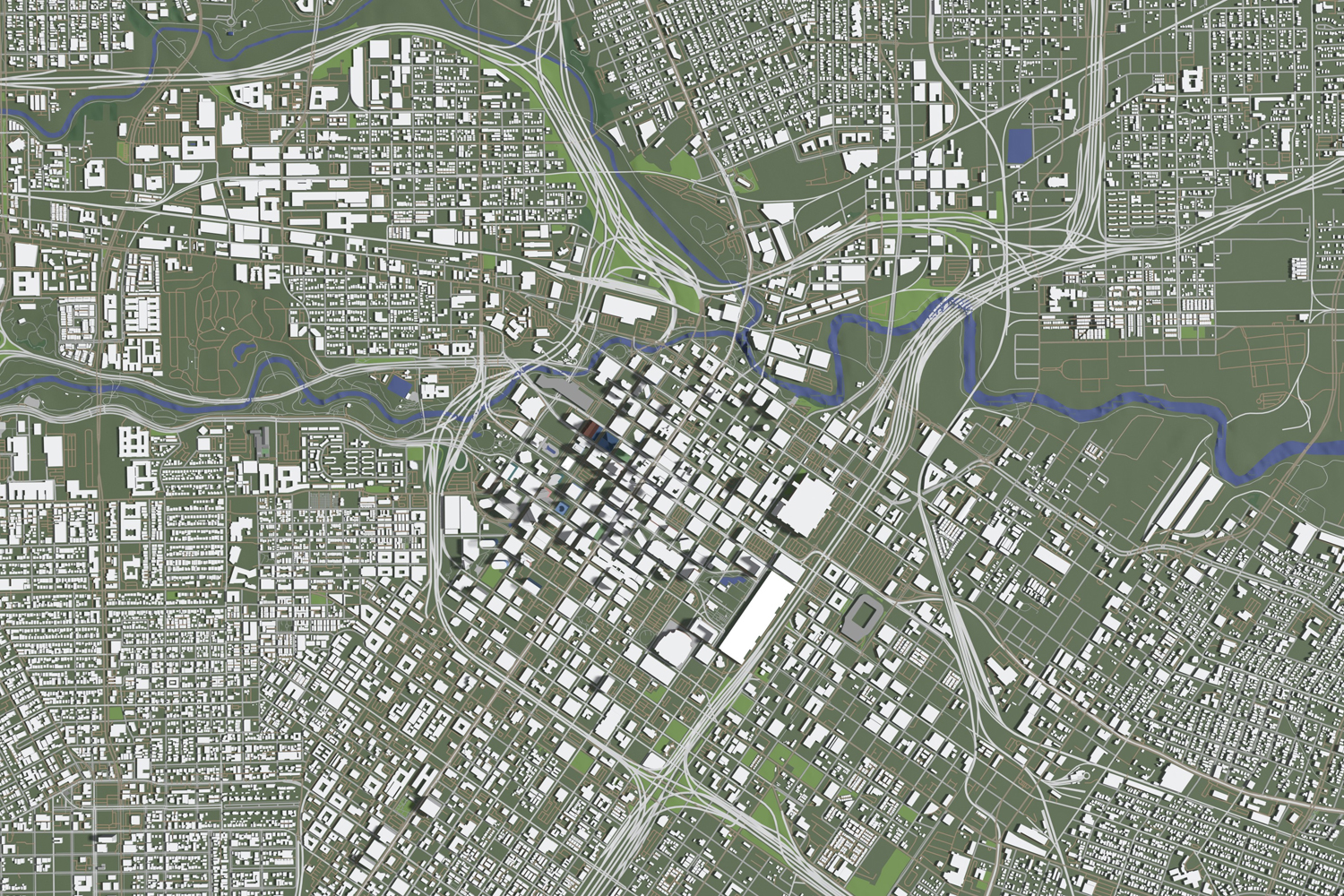

The ongoing RESPOND study, on which Gomez is a researcher, is examining the link between cancer disparities and structural racism. One of the analyses they’ve run explores the relationship of redlining—measured in this study by the disproportionate denial of loans in a patient’s census tract relative to the surrounding region—and disparities in prostate cancer. Gomez said they found that Black men with prostate cancer were much more likely to live in areas with high levels of loan denial. When they explored factors that might connect redlining to the disparity, they found that neighborhood socioeconomic status explained 54% of the effect of redlining on overall mortality and 29% of the effect on prostate cancer-specific mortality.

“These are the factors existing at the structural and institutional levels,” Gomez said. And as they reach people differently along lines of race, gender, class and other identities, “they then produce disparities in the social drivers of health and in individual-level health behaviors and health outcomes.”

In another part of the session, Lauren McCullough, an epidemiologist at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta and visiting scientific director at the American Cancer Society, delved into disparities and some of the common explanations offered for them using data from the BRIDGE surveillance cohort.

The BRIDGE cohort includes 52,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer in Georgia from 2010 to 2017. McCullough, whose presentation was recorded for the session, noted that mammography rates in Georgia are balanced, with 77% of white women and 80.5% of Black women reporting that they have been screened in the past two years. But while mammography is a popular target for interventions to address disparities, it is just one part of a process; screening only works if people who get irregular results follow up with diagnostic mammograms and biopsies.

The researchers found that despite the balance in getting mammography Black women had a 42-day delay in getting a breast cancer diagnosis after screening, compared with 25 days for white women. Low socioeconomic neighborhood status, inadequate or no insurance, and being single were also associated with greater delays. But the largest factor in whether screening was delayed was race, with Black women twice as likely to have a delayed diagnosis as white women, and that delay was seen both between the screening mammogram and the diagnostic mammogram and between the diagnostic mammogram and the biopsy.

“There is an urgent need to understand the barriers to return after screening and create interventions to support timely diagnosis,” McCullough said.

McCullough also identified the importance of neighborhoods, and neighborhood deprivation, as a factor in health outcomes. “Socioeconomic indicators tend to cluster in neighborhoods, things like employment and education and poverty,” she said.

But McCullough warned against relying on a single measure to fully explain disparities. Research found that higher neighborhood deprivation was associated with a rise in breast cancer mortality in white women, but for Black women, rates did not change with neighborhood deprivation. McCullough said Black women are affected by multiple social and structural stresses, so while changing one factor may show a direct effect on health outcomes in some populations, it may not reflect as much change in the experience of Black women.

“This is more than neighborhoods, this is more than socioeconomic status, and more than generational wealth access. It’s generational privilege, it’s generational power, and those are the things that we need to address if we’re going to narrow disparities,” McCullough said.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.