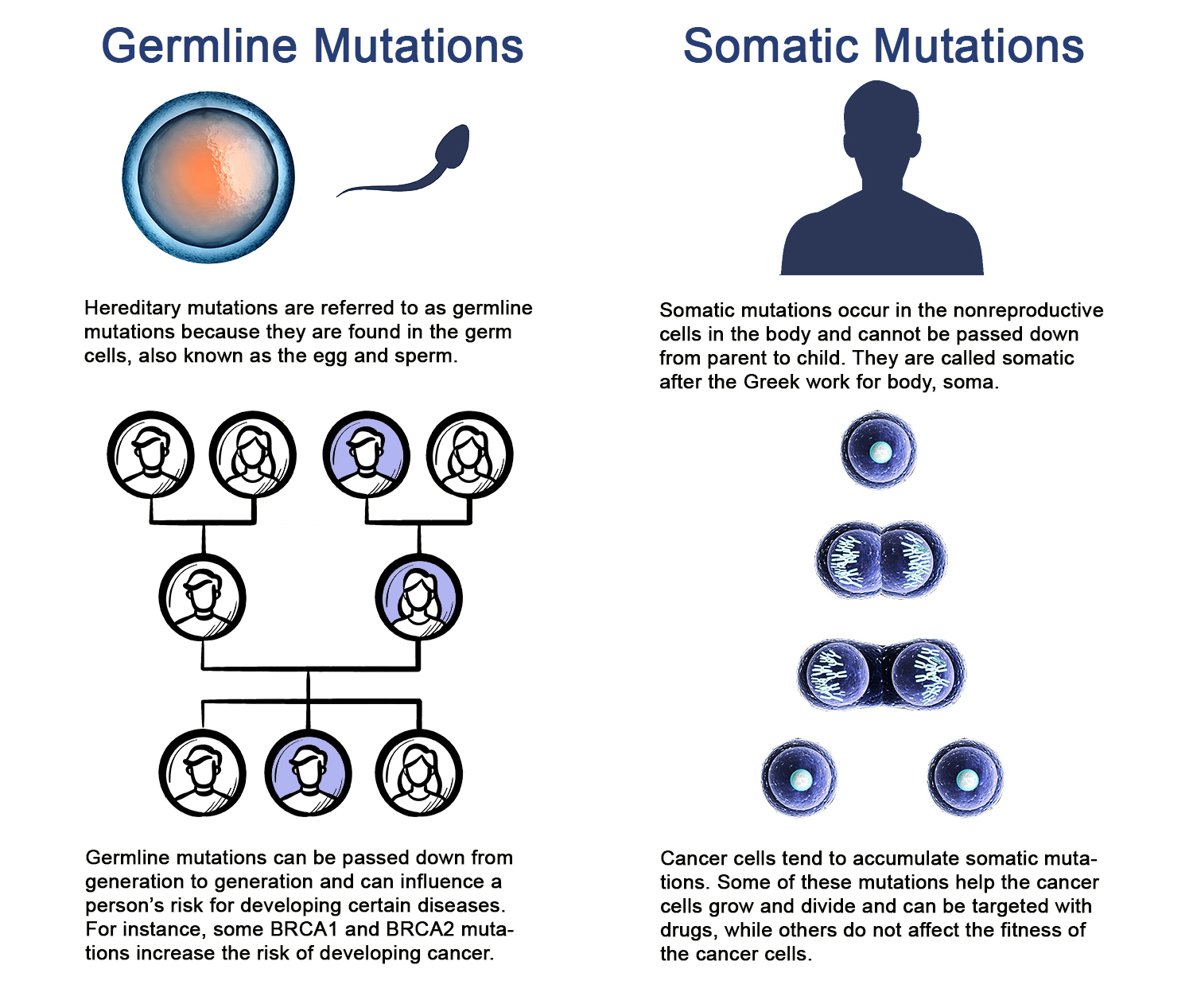

WHEN MOST PEOPLE get a DNA test, they want to find out about the DNA sequence they were born with. This type of genetic testing, called germline testing, can tell people about their ancestry, as well as their and their family members’ risk of developing health conditions, including some inherited cancers.

Cancer patients may also get a second type of DNA test that zeroes in on the DNA in their cancer cells. These tests are intended to reveal somatic mutations, or mutations that cells in the body acquire as they grow and divide. Many cancer patients do not fully understand the purpose of these tests, according to data presented Sept. 9, 2019, at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Barcelona, Spain.

Researchers conducted phone surveys of patients who participated in the Lung-MAP trial, a precision medicine trial for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer supported by the National Cancer Institute. Patients undergo tumor DNA testing to see if they might be a “match” for certain treatments based on the mutations found in their cancer cells. If they are a match, they are treated with a drug that may be effective against cells with that mutation. If there is no match, they can still receive an immunotherapy combination being tested in the trial. The Lung-MAP trial has enlisted more than 2,000 patients since it began in 2014, and the researchers surveyed 123 of these patients. The median age of the survey participants was 68 years, 95% were white and 22% had a college degree.

Testing tumors for mutations, the type of testing done for the Lung-MAP trial, does not provide information about familial cancer risk or personal risk for other diseases. Patients in need of this type of information would need to get a separate test that would look at the DNA of normal, noncancerous cells in their body. This distinction is explained to study participants when they sign an informed consent form, but Joshua Roth, who studies the risks and benefits of genomic testing for cancer patients at the Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research in Seattle, wondered if patients truly understood what they would learn from the trial.

Infographic by Kate Yandell / solar22 / RaStudio / frentusha / newannyart / koya79 / iStock / Getty Images Plus

“There’s a lot of information to express, and it’s not entirely surprising that some of this falls through the gaps,” says Roth, who presented the new data. “We found that gap was actually quite large, and I think that suggests we need to figure out interventions to really close those gaps and improve knowledge.”

Roth and his team found that 83% of patients surveyed said they understood the benefits of enrolling in the trial, and 73% said they understood the risks. When the team began asking more specific true-or-false questions, the answers were less clear. Most of the patients, or 87%, knew that the results of their genomic testing would help with selection of their treatment. However, only 12% percent knew that the tests would not reveal information about their risk for developing diseases other than cancer. And only 8% of participants surveyed answered correctly that the data would not tell them about their family members’ risk for cancer. The remaining participants either answered the questions incorrectly or said they didn’t know the answer.

Misunderstandings of this type are unlikely to hurt patients, says bioethicist Spencer Hey of the Harvard Center for Bioethics in Boston, who was not part of the study. But it “might undermine their trust in the research,” he says. Hey studies clinical trial ethics.

Roth adds, “We don’t want patients to think that they’re going to be receiving certain types of information that they’re not really [receiving], because that might drive the decision to participate.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.