Every week, the editors of Cancer Today magazine bring you the top news for cancer patients from around the internet. Stay up to date with the latest in cancer research and care by subscribing to our e-newsletter.

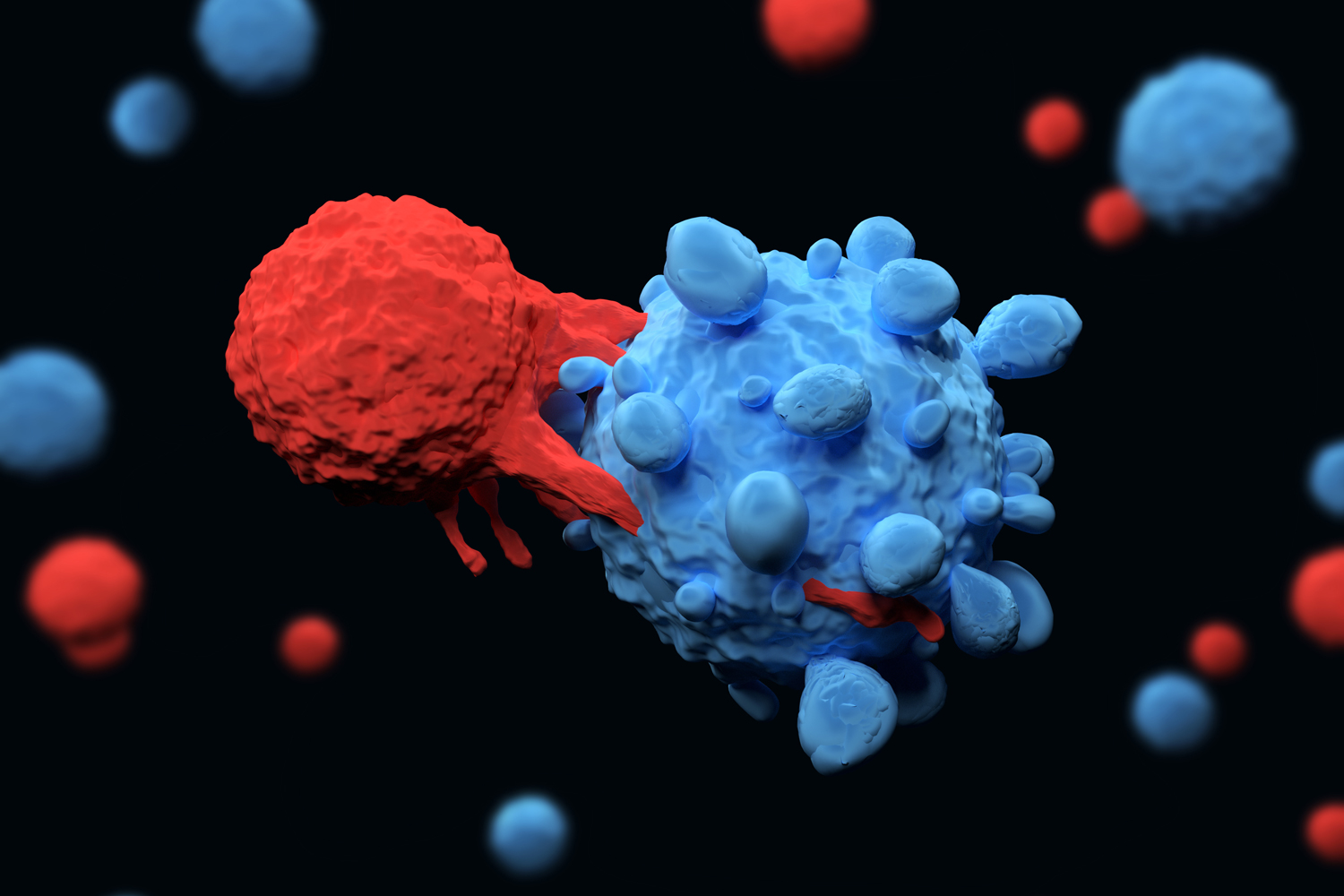

FDA Investigating New Cancers After CAR T-Cell Therapy

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced Nov. 28 that it is investigating the development of cancer in a small number of patients who received CAR T-cell therapy to treat their cancer. In chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a patient’s T cells are removed from their body, genetically engineered to recognize and kill cancer cells, and then infused back into the patient. The FDA said it received 19 reports of new blood cancers developing in patients after receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Since 2017, the agency has approved six CAR T-cell products to treat various types of blood cancer, and the therapies have extended the lives of thousands of patients, according to cancer specialists. The FDA stated that, despite the warning, the benefits of CAR T-cell therapy far outweigh the risks. Doctors who use the treatments agreed. In a New York Times story, hematologist-oncologist John DiPersio, director of the Center for Gene and Cellular Immunotherapy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said his center had treated 500 to 700 patients with CAR T-cell therapy, and he didn’t see any cases of new cancer developing. “They are all going to die and they are all going to die quickly without this treatment. It saves their life,” DiPersio said of patients who receive the treatment after other therapies have failed. “It works in a substantial portion of patients. The benefit is enormous.”

Precision Therapies Not Available for Most Cancer Patients

Precision cancer treatments that target mutations in cancer cells as a way to treat the disease are growing in importance. But most cancer patients don’t benefit from them because their mutations aren’t treatable with currently available therapies. According to a study published in Cancer Discovery, the percentage of tumor samples analyzed that had actionable mutations, that is, alterations that are treatable, increased from 18.1% to 35.9% between 2017 and 2022. Despite this gain, the study found that most FDA-approved precision oncology drugs target only a few biomarkers, leaving most patients without a precision drug to treat their cancer. “Our study shows that as of October 2022, almost two-thirds of patients do not have viable precision oncology options for treatment, despite 43% of currently FDA-approved therapies being precision oncology therapies that require biomarker testing for patient selection,” molecular geneticist and study author Debyani Chakravarty of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City said in a Healio article.

Hospitals Treating Racial and Ethnic Minorities Offer Fewer Cancer Services

A study published in JAMA Oncology found that hospitals serving large numbers of Black and Latino patients are less likely to offer advanced medical treatments that could improve the quality and effectiveness of cancer care. Lower funding and lack of resources at these hospitals create disparities in cancer screening and treatment that could lead to worse outcomes for patients, compared with patients treated at other hospitals, researchers found. Hospitals serving large numbers of minority-group patients “can’t do their job without adequate financial and physical resources,” resident physician and study author Gracie Himmelstein of the David Geffen School Medicine at UCLA in California said in a Healio article. “Our fragmented hospital payment system pays lower fees for the care of Medicaid-insured or uninsured patients,” she added. “This unjustly compromises cancer services, and potentially cancer outcomes for poor and minority patients, and is just one of the myriad ways that structural racism plays out in our health care system.” Himmelstein called for equal distribution of resources for health care across all settings and for further research to better understand the connection between access to cancer care resources and patient outcomes. “It feels pretty self-evident that not having access to the resources to receive gold-standard cancer care would be bad for outcomes, but it would be interesting to look at [how it] plays out in the data,” she said.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.