IN JUNE 2016, Whitney Hayden’s life was upended when her 34-year-old husband, Adam, was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. The family’s schedule, already strained by their three children ranging in age from 8 months to 4 years, would now have to integrate Adam’s ongoing treatment and the changes to his physical capabilities. The Haydens sold their home in Indianapolis and moved in with Adam’s parents for extra support.

Glioblastoma affects the brain or spinal cord and can develop at any age, but it’s most common among older people. Faced with an uncertain future for her young family and only 35 years old herself, Hayden felt isolated and alone. In October 2016, she decided to start a blog called Faith, Hope, and Wine to keep in touch with their circle of friends and family members. The blog allowed her to inform everyone of new developments, but her writing unexpectedly attracted new readers connected to her only through shared experiences of cancer.

“Hearing from others in a similar situation has been one of the unexpected upsides of this,” she says. “I guess I didn’t ever think about people reading [the blog] and reaching out and telling me their stories.”

A study published in 2013 in Sociology of Health & Illness analyzed 37 interviews with people affected by various health conditions who shared their experiences across several forms of media. Many people described how reflecting publicly on their experiences helped them and seemed to help others who read their posts. Whether through blogs, social media, zines (homemade printed publications) or something else entirely, people with cancer and their loved ones are finding ways to express their thoughts and concerns and build bridges to others with similar experiences.

Blogging the Honest Truth

Hayden’s unwillingness to sugarcoat the realities of living with Adam’s glioblastoma makes some of her posts uncomfortable reading. “The honest truth is not pretty,” begins an entry titled “The Truth.” “But it’s always better to tell the truth so that’s what I’ll try to do. I want [to] be honest in the fact that we are struggling.” In the post, Hayden reflects on the 28 months following Adam’s diagnosis, weaving in references to Adam’s brother’s wedding and Whitney’s work life. The juxtaposition of significant moments in Adam’s illness with scenes from day-to-day life demonstrates how cancer intrudes on normalcy.

Whitney Hayden and her husband, Adam. Photo courtesy of Whitney Hayden

Hayden has received emails from readers all over the world who have found something in her writing that speaks to their own lives. Knowing that someone else out there experiences the same struggles—even if they’re hundreds or thousands of miles away—can help readers feel less isolated.

“I’ve made some connections through this experience that I think will be lifelong connections,” says Hayden. “Even though we have a very strong, supportive community, and I have the best friends in the world who I would never have made it through this without, none of them has had a husband with terminal cancer and small kids. There are some things you can’t put words to, and you can’t understand until you live it.”

Tapping Into Twitter

When her mother was diagnosed with stage IIIB lung cancer in 2012, Deana Hendrickson, now 60 and living in Los Angeles, wanted to spend as much time as possible with her. While sitting in waiting rooms or by her mother’s bedside during extended hospital stays, Hendrickson began exploring Twitter, a social network of hundreds of millions of people worldwide who communicate in short posts of up to 280 characters. She discovered free-flowing exchanges among people affected by breast cancer that were tagged with #bcsm, which stands for “breast cancer social media.” The hashtag serves as a virtual signpost to help those affected by breast cancer find discussions and share their firsthand experiences, with a focus on regularly scheduled conversations on topics ranging from treatment options to the realities of survivorship.

Hendrickson searched for the #lcsm hashtag for lung cancer and found only a handful of tweets from radiation oncologist Matthew Katz of Lowell General Hospital in Lowell, Massachusetts. The two began discussing ways to build a larger lung cancer social media community.

Deana Hendrickson, right, and Janet Freeman-Daily stand with medical oncologist Jack West. The trio have worked together in developing the #lcsm chat. Photo courtesy of Janet Freeman-Daily

“It was not an original thought on my part—I loved what they were doing with #bcsm and I wanted to do something for lung cancer,” says Hendrickson. From the beginning, she felt strongly that the #lcsm community should have a focus on science and education. She sought the help of researchers, medical professionals and advocates, who agreed to take part in Twitter chats and use the hashtag. She also enlisted the help of Janet Freeman-Daily, a lung cancer survivor with a background in engineering, to be the linchpin for conversations that straddled the personal and the scientific.

“Lung cancer treatments are changing really fast,” says Freeman-Daily. “It’s important to me, as a patient, to see that other patients try and get the best possible care, so we’re trying to educate people about their options, and about being able to speak up for themselves, and being able to take part in shared decision-making, because I think it saves a lot of lives.”

Since the first Twitter chat in July 2013, #lcsm has seen its numbers grow dramatically. Despite the relatively loose sense of affiliation offered by a shared Twitter hashtag, the content and community of #lcsm seem to create a welcoming feeling for users. A study published June 10, 2019, in npj Digital Medicine found that the Twitter hashtags #lcsm and #LungCancer had a higher percentage of posts categorized as “companionship support,” defined as support intended to offer a sense of belonging, compared with a lung cancer support group on Facebook and a lung cancer discussion forum.

Hendrickson, who wasn’t deeply involved in social media before becoming a part of #lcsm, now feels close to the people she has met, whether in person or online. “Everybody is connecting via social media, and I think it’s outstanding,” she says. “Because we’re all over the country—all over the world.”

For those who take part in #lcsm, gathering with other lung cancer patients and survivors can also provide a break from the stigma they might feel elsewhere. To many people, lung cancer still carries a strong association with tobacco use, and even well-meaning comments from others can place blame for the illness on those who have it. Making a supportive space with the sole intention of discussing lung cancer encourages people with the disease to talk openly with like-minded and accepting people.

Using Zines to Create Community

Thanks to the internet, it’s easier than ever for people to find others who have similar experiences. That’s how Roman Ruddick, who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2013, and Charlie Manzano, who was diagnosed with stage IIA melanoma in 2016, and then with stage IIIB melanoma in 2018, found each other in 2017. They were both blogging about their experiences as transgender cancer patients in order to provide support to other trans people with cancer. They began messaging each other via the internet and met in person for the first time a few months later.

In the spring of 2018, Ruddick, now 24, and Manzano, now 20, attended a zine fest in San Jose, California. Zines are typically created by individuals or small groups and are geared to specific audiences. Ruddick, who is from Medford, Oregon, observed marginalized communities using zines to spotlight underrepresented voices and saw an opportunity to do the same for transgender people affected by cancer. The do-it-yourself ethos among zine creators seemed conducive to creating something truly authentic. “We were both so inspired by the social justice projects happening there for the purposes of community instead of profit,” remembers Manzano. “Something just sort of clicked.”

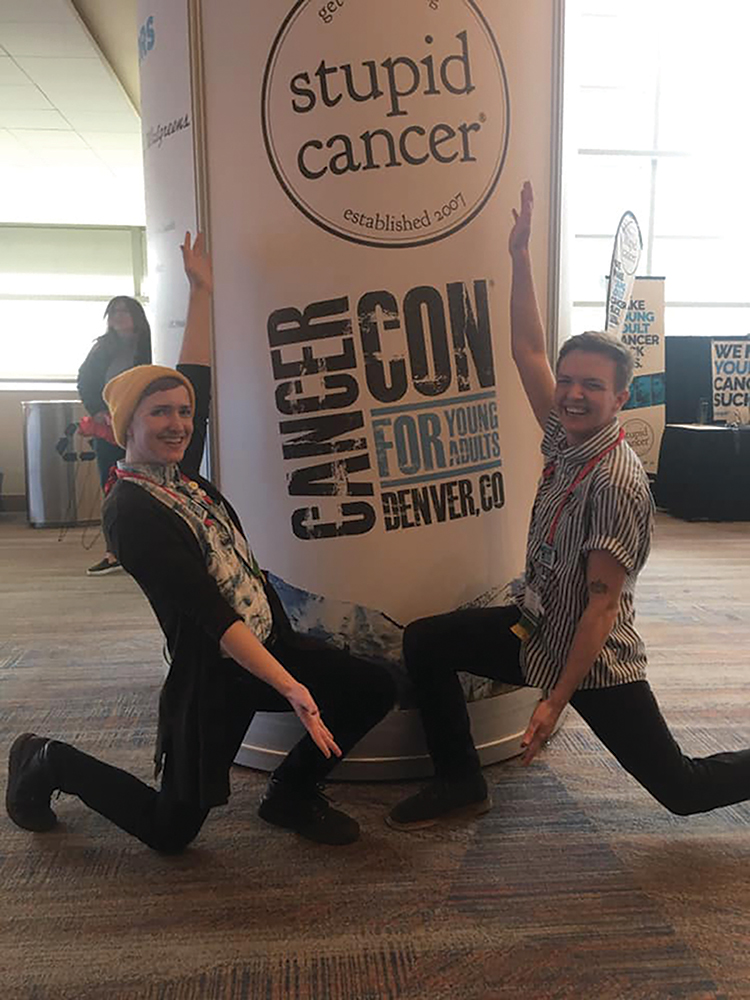

Charlie Manzano, left, and Roman Ruddick attend CancerCon in Denver in April 2019. Photo courtesy of Charlie Manzano and Roman Ruddick

Ruddick and Manzano, who now share a residence in Martinez, California, started out producing zines that captured a single facet of their experience or addressed one issue in detail. For instance, Manzano wrote a zine about the facial disfigurement resulting from his cancer, and Ruddick wrote one about the perceived rarity of young people getting diagnosed with cancer. These zines were made available online under the banner of the Transgender Cancer Patient Project, a website the pair set up to publish their works, and that now includes community resources, an event listing and educational opportunities. In addition, printed copies are distributed at community events and conferences.

Despite having different types of cancer, Ruddick and Manzano found parallels in the lack of support they received as they navigated the health system as trans people. Hoping to capture their experiences and those of others, they began conceptualizing a zine that would be released in the summer of 2019 under the name Transpire. “The hope with Transpire was to create community, offer emotional support and connection, and show that [the experiences and needs of a transgender cancer patient] are not as big an anomaly as society might think,” says Ruddick. In contrast to their previous zines, Ruddick and Manzano were eager for Transpire to feature a number of voices expressing similar but distinct experiences, hoping that any trans person with cancer who reads them might draw strength from the fact that others have weathered similar circumstances.

Several trans people who had been diagnosed with cancer reached out, looking to contribute writing and art to the project. The finished product is a collection of honest, open reflections on diagnosis, treatment and recovery that allow readers to draw parallels between experiences, while also recognizing differences that make each entry personal.

When Ruddick and Manzano were blogging, they became aware of the often-unspoken demands on cancer patients to present their stories in ways that depict their bravery as an inspiration for others. In response, the Transgender Cancer Patient Project and Transpire make a space for more honest discourse about cancer through a different lens.

“A big struggle is finding a space where we can be trans and be cancer patients,” explains Ruddick. “Many cancer support groups have gendered aspects that put trans people in uninclusive situations, and as a young person I’ve been met with a lot of uncomfortable silences when I bring up cancer in trans peer groups. But our experiences with cancer and gender greatly influence each other, and they can’t exist void of the other.”

Ruddick cites their own experience as a transgender cancer patient in a society where certain illnesses are gendered—norms that make it impossible for them to talk about having ovarian cancer without also talking about being transgender—to illustrate the intersectionality between illness and gender.

As a means of hastening social change, Ruddick and Manzano also make zines that are explicitly intended to educate groups outside of their audience of transgender cancer patients. Ruddick wrote a zine called A Pocket Guide to the Gender Neutral Patient that advises health care providers on the basics of caring for nonbinary patients, while Manzano penned How to Talk to Me, which helps friends and relatives of cancer patients navigate conversations about cancer with their loved one. Making zines that can be widely reproduced and distributed via the internet and in print allows the Transgender Cancer Patient Project to have a significant reach and impact. These guides are meant to direct and guide social change, says Ruddick. “Trans people—and any person with a marginalized identity, including cancer patients—are the only people that can truly talk about their experiences from their perspectives, so I think that it’s important for education to involve us, or better yet, come directly from us.”

Read about cancer patients’ and caregivers’ experiences in their own words.

Faith, Hope, and Wine: 849 Days

In honest and open fashion, Whitney Hayden describes how new challenges and breaking points can arise well after diagnosis.

Transgender Cancer Patient Project: Fill in the Blank

This zine draws a parallel between the unsolicited comments and questions author Charlie Manzano receives as a cancer patient and those he receives as a transgender person.

#lcsm: Slicing the Pie

This discussion takes full advantage of the broad spectrum of people who participate in #lcsm chats by exploring how clinicians and researchers can play productive roles in patient communities.

Finding a Voice

Whether the goal is to inform, to help process difficult emotions, or to create a safe place for expression, these outlets help many people affected by cancer to articulate their unique experiences—on their own terms.

“Sometimes I lay my head down at night and think, ‘This sucks,’” says Hayden. “And I would never want anyone to go through this, but I do think, ‘Man, is there anybody else out there that’s feeling the way I feel right now?’”

Thanks to her efforts and those of others, cancer patients and caregivers know they are not alone.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.