GERALDINE A. FERRORO recalled in a memoir the “cosmic” force she felt as she walked into the Moscone Center in San Francisco on July 19, 1984, to accept the Democratic Party’s nomination for vice president—the first woman selected for the office by a major political party.

“By choosing a woman to run for our nation’s second highest office, you send a powerful signal to all Americans,” Ferraro said in her acceptance speech that night. A sea of delegates, some in tears, waved flags and stomped their feet for the nominee. “There are no doors we cannot unlock,” she added. “We will place no limit on achievement. If we can do this, we can do anything.”

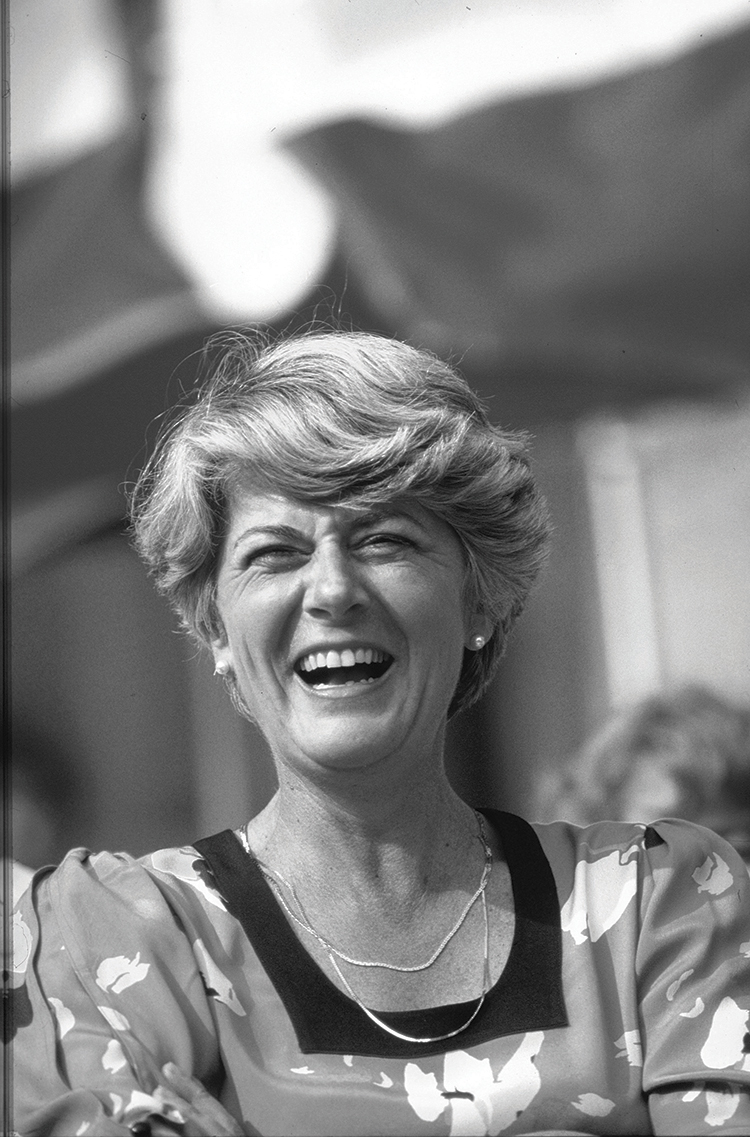

Vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro waves to the crowd at a campaign rally in Atlanta on Oct 3, 1984. Photo © AP Photo.

Ferraro’s “cosmic” moment running with Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale would be the high point in what turned out to be a losing campaign against incumbent President Ronald Reagan and Vice President George H.W. Bush. Mondale and Ferraro gained electoral votes only from Mondale’s home state of Minnesota and the District of Columbia. But Ferraro’s quick wit and down-to-earth style resonated with many Americans.

The candidate held her ground on numerous occasions when she was patronized as a female politician. During a campaign stop at a Mississippi farm, the state’s agricultural commissioner asked, “Can you bake a blueberry muffin?”

“Sure can,” Ferraro shot back. “Can you?”

Long after the cheers and political fervor subsided, Ferraro combined her political savvy and genuine concern for others to advance research on multiple myeloma, a blood cancer she was diagnosed with in 1998 and kept private until 2001, when she shared her personal story to help get legislation passed to increase federal research funding.

‘Taking a Man’s Place’

Born on Aug. 26, 1935, in Newburgh, New York, about 60 miles north of New York City, Ferraro was the daughter of Antonetta Corrieri, a skilled beadworker, and Dominick Ferraro, an Italian immigrant who owned a restaurant and a five-and-dime store.

Ferraro was the couple’s fourth child and only daughter. Her mother regularly supported the little girl, for example, when she wanted to dress as Uncle Sam instead of Miss America for Halloween. “It doesn’t make any difference whether you’re a boy or a girl,” Ferraro recalled her mother saying. “You can be whatever you want.”

When Ferraro was 8, in May 1944, her father died of a heart attack at the age of 45. She described the event as a “dividing line” that ran through her life. Ferraro’s mother sold everything, moved to the South Bronx section of New York City in 1945 and began working countless hours—doing her painstaking beadwork day and night and cooking on weekend nights at her small restaurant.

“I was no longer anyone’s princess,” Ferraro wrote in her book Framing a Life: A Family Memoir, describing a time of lonely struggle. “I was suddenly forced to concentrate on lessons I would never forget—the importance of always having another plan at the ready, the realization that nothing can ever be taken for granted.”

Ferraro was a bright, hard-working student and earned a scholarship to Marymount College in Tarrytown, New York. She attended classes at the school’s Manhattan location. Though she had ambitions to be a newspaper reporter, her mother urged her to pursue teaching as a more stable profession.

Ferraro was 20 when she received her teaching degree and began to educate second-graders in New York City public schools. She continued to pursue her passion for learning by attending law school at night at Fordham University. Ferraro recalled a person in the Fordham admissions office telling her, “I hope you’re serious, Gerry. You’re taking a man’s place, you know.”

Undaunted, she passed the New York State Bar exam the same year she graduated from law school and just a few days before her wedding on July 16, 1960, to real estate developer John A. Zaccaro, whom she met in a Greenwich Village club while still in college.

Although she was serious and energetic, major law firms were reluctant to hire women in 1960, and Ferraro was overlooked when she applied. She spent the next 13 years raising their children—Donna, born in 1961; John, born in 1964; and Laura, born in 1966—while doing pro bono legal work for women in family court and diving into community activism.

Ferraro started her first government job in 1974 as an assistant prosecutor in the Queens district attorney’s office in New York City, and she became head of the Special Victims Bureau a little more than three years later. The experience opened her eyes to social injustices committed against women, children and the elderly, and the lack of legislation to protect them. Her frustration fueled her political aspirations, and in 1978 Ferraro ran a grassroots campaign for the U.S. House of Representatives. With her law-and-order background and the slogan, “Finally, a tough Democrat,” she was elected in the Ninth Congressional District in Queens with 54 percent of the vote. She was one of only 17 women in the U.S. Congress in 1979 and would serve three two-year terms in the House.

In the nearly six years before she became the first woman to run on a major-party ticket, Ferraro’s can-do attitude became well-known in the House. She earned the respect and friendship of House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr., who described her as “solid as a rock” and appointed her to the important House Budget Committee. Her legislative achievements included sponsoring the Economic Equity Act, which reformed pension options for women.

A Clinical Trials Pioneer

Following the 1984 presidential campaign, Ferraro traveled across the country raising money for Democrats and female candidates. From 1988 to 1992, she taught as a fellow at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics. Ferraro would go on to be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Human Rights Commission and a co-host of the political talk show Crossfire, in addition to lecturing, writing and building a reputation as a public policy expert.

The 63-year-old Ferraro had just completed an unsuccessful run for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate from New York when she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in late 1998. At the time, Ferraro had no symptoms, but as part of a checkup, her internist noticed her blood test results over the years showed a gradual increase in white blood cells. Additional tests confirmed that she had the disease.

American Cancer Society: Multiple Myeloma

International Myeloma Foundation

Multiple myeloma starts in the plasma cells in bone marrow, the spongy tissue found inside bones. Myeloma cells may begin to interfere with the processes that keep bones healthy. The illness is commonly experienced as bone pain, bone weakness and fractured bones. These symptoms don’t usually occur until the disease has progressed, however, which makes it difficult to diagnose early.

Physicians who suspect a patient has multiple myeloma may start by taking blood and urine samples to measure the amounts of certain antibodies and other proteins made by the myeloma cells. An abnormal amount of these substances may be a sign of the disease. Doctors could also order tests such as bone marrow biopsies, skeletal surveys and magnetic resonance imaging to confirm the diagnosis and determine the extent of cancer in the body.

Ferraro’s multiple myeloma was identified at an early stage and was initially considered inactive. She didn’t show any of the common myeloma symptoms, nor were certain proteins in her blood or urine elevated. Though immediate treatment wasn’t required, Ferraro’s oncologist prescribed monthly infusions of a bone-strengthening drug called Aredia (pamidronate) and closely monitored his patient with frequent bone marrow biopsies and blood and urine tests. About 18 months after her diagnosis, she learned in June 2000 that her multiple myeloma had become active.

Fortunately for Ferraro, researchers had been studying Thalomid (thalidomide) as a possible new treatment for multiple myeloma. A landmark trial published in 1999 in the New England Journal of Medicine analyzed the drug’s effectiveness in 84 patients with multiple myeloma who were no longer responding to chemotherapy. Thirty-two percent of the patients who took oral thalidomide for a median of 80 days responded to the drug, as shown by a reduction in blood and urine levels of paraprotein, an abnormal protein indicating myeloma.

Ferraro consulted with myeloma expert Kenneth C. Anderson, an oncologist and cancer researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. They discussed next steps, including a possible stem cell transplant. But Anderson was able to offer alternatives such as Thalomid, Revlimid (lenalidomide) and Velcade (bortezomib).

Ferraro, never afraid to take risks, enrolled in the earliest clinical trials of Velcade and Revlimid—before their approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat multiple myeloma. The FDA approved Velcade in 2003 and Revlimid in 2006.

“Geraldine was a pioneer and a hero to me, to caregivers and to patients nationally and internationally in many ways,” Anderson says. “One way is that she had the courage and the willingness to participate very early on in clinical trials. She was in fact enrolled in the earliest clinical trials of lenalidomide and bortezomib, back when they were just being tested in terms of finding the right dose and schedule.”

The Political and Personal Intersect

Ferraro, with Anderson present, publicly disclosed her illness in June 2001 while testifying before a Senate health subcommittee in support of the Hematological Cancer Research Investment and Education Act, which dedicated $250 million in federal funds to blood cancer research.

“Gerry was in the gallery when the House passed the bill, and it was very, very touching,” says former Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas, who introduced the legislation with Sen. Barbara Mikulski, a Democrat from Maryland. “We were happy because we knew there were going to be people who would have treatments that they never would have known about before.”

Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman nominated for vice president on a major-party ticket, lived for more than a decade with multiple myeloma. She died from cancer-related complications in March 2011. Photo by Bill Pierce / The Life Images Collection / Getty Images

Former President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on May 14, 2002, with Ferraro, Hutchison and Mikulski standing beside him. As part of the legislation, Congress also earmarked $5 million to create the Geraldine Ferraro Blood Cancer Education Program to accelerate awareness of new blood cancer therapies, treatment options and clinical trials.

Through speaking engagements and events, Ferraro used her illness to increase awareness of multiple myeloma and other blood cancers and would speak with patients on the phone, referring them to experts, clinical trials and drugs while using her sense of humor to help them persevere.

“I think Gerry was trying to say to everybody, ‘You can ask these questions. Don’t be nervous about being proactive in your care. Make sure you’re looking for every option available to you,’ ” recalls Kathy Giusti, who was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 1996 and soon after founded the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation with her twin sister.

Ferraro lived more than a decade with multiple myeloma, which was two to three times longer than what would have been predicted prior to the new drugs that became available when she began treatment, Anderson says. She died at age 75 from cancer-related complications on March 26, 2011.

Exploring All Options

The five-year relative survival rate for all multiple myeloma cases rose steadily from 26.6 percent in 1975 to 45.1 percent in 2007, and treatments have continued to advance.

“We have seen seven new drugs approved in the last decade,” says Giusti. “We have three new drugs that we expect to be approved in the next nine to 12 months. Two of those drugs are in the incredible, fast-growing field of immune therapy. And one is an oral proteasome inhibitor, which is looking incredibly promising.”

Advances in multiple myeloma treatment continue to come, as scientists combine drugs to try to produce better results. For example, a study in the Jan. 8, 2015, New England Journal of Medicine indicated that the addition of the drug Kyprolis (carfilzomib) to Revlimid and dexamethasone increased progression-free survival by more than eight months, compared with Revlimid and dexamethasone alone.

“There really has been remarkable progress, and I do think the best is yet to come,” says Anderson of Dana-Farber. He credits patients like Ferraro as the inspiration for his pursuit of rapid development of drugs for multiple myeloma.

“She lived a very full life every day in spite of her multiple myeloma,” Anderson says of Ferraro. “She approached her disease like she approached other things—with a zest to face challenges head-on. Geraldine didn’t accept the standard often and was always striving to make the world a better place.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.