“Cancer survivor.” Many people who receive a cancer diagnosis hear this term applied to them. Does it convey hopefulness and accomplishment? Or is it inadequate and even hurtful? A study published Jan. 7 in the Journal of Psychosocial Oncology indicates that while some people embrace being cancer survivors, others do not identify with the title.

The term “cancer survivor” has had many definitions over the years. Physician Fitzhugh Mullan used the term in an influential 1985 essay, defining survival as beginning “at the point of diagnosis.” Mullan, who is sometimes credited with popularizing the term, had himself been diagnosed with cancer and went on to be a co-founder of the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. Today, many organizations, including the National Cancer Institute, say that people are cancer survivors from diagnosis through the end of life. However, others define the term as referring only to people who have completed treatment, or only to people who have no evidence of disease. In practice, the label is used for people at all stages of all cancer types.

“It really interested me because in marketing, we’re trained early on … that when you use one word to describe a heterogeneous group of people, you’re asking for trouble,” says Leonard Berry, a marketing professor at Texas A&M University in College Station who co-authored the study.

Berry and his co-authors asked members of the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation Army of Women—an initiative that connects breast cancer research studies with participants—to evaluate their feelings about “cancer survivor.” The 1,401 respondents to the survey were predominantly women who had received a breast cancer diagnosis.

In a quantitative portion of the survey, respondents rated their level of agreement with the statement “I identify myself as a ‘cancer survivor’” on a seven-point scale. They also rated their feelings about the term on a scale from 0 (negative) to 100 (positive). Answers to both questions returned slightly above neutral levels of agreement or positivity. Those in active treatment or in more advanced stages of the disease were less likely to have positive reactions.

Participants also answered the open-ended question “What is your personal opinion about the phrase ‘cancer survivor’ and why do you feel as you do?” Their responses were grouped into themes. The most common positive theme was that the term promotes a sense of accomplishment (about 14 percent of total responses). The most common negative response was that the term disregards the fear of recurrence (about 16 percent of total responses). Of all open-ended responses, nearly 60 percent were negative, about 29 percent were positive and nearly 11 percent were neutral.

Berry acknowledges the study’s many positive responses about the term “cancer survivor.” But when more than half of the open-ended answers had negative reactions—some revealing anguish—he and his co-authors posed a question in their paper: In a profession guided by “first, do no harm,” is it harmful to use “cancer survivor” as a blanket term?

One participant’s answer to the open-ended question especially affected Berry: “I never self-identified as a ‘survivor’ and now that I am metastatic I am angry that the lie of survivorship is perpetrated on us.”

“The language that we’re routinely using is creating needless anxiety and emotional harm,” Berry says. “What we’re asking is: Why are we doing that?”

The term “survivor” is part of a larger family of battleground terminology used to talk about cancer, says Shelley St. Godard of Vancouver, British Columbia, who was diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer in 1996 and metastatic breast cancer in 2013. St. Godard, who participated in an online discussion of the paper, does not identify with “survivor.”

“We do feel like we’re battling a disease, but by connotation, when we die, we fail,” St. Godard told Cancer Today. “I respect people who identify as a survivor, but I don’t see why anyone would want to identify themselves so closely with the disease. I’m someone living with a terminal disease who’s living the best life I can.”

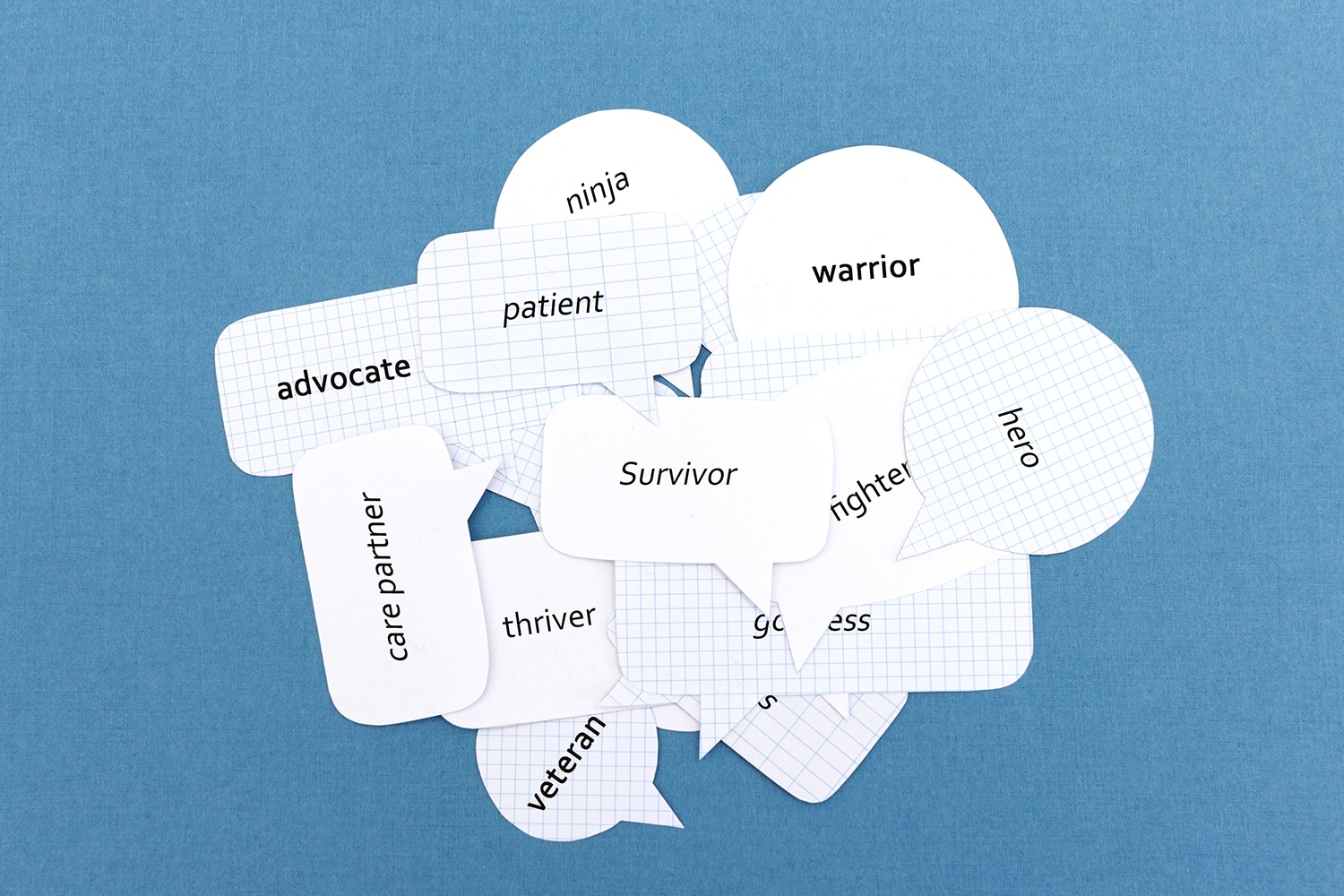

Deanna Attai, a breast surgeon at UCLA Health Burbank Breast Care in California, who was not involved in the study, says that online discussions taught her how divisive “cancer survivor” is and showed her some ideas for new labels, including “warrior,” “thriver” and even “badass.” Some people prefer no label at all. People’s terminology preferences are rooted in their personal experiences of cancer.

Attai co-moderates the weekly #BCSM Twitter chat about breast cancer, which on Feb. 4 focused on the word “survivor.”

Attai now follows each patient’s lead: If a patient celebrates a milestone, she celebrates with that patient. If a patient is fearful of recurrence, she is more measured. If a patient uses the term “survivor,” she will, too. But she no longer assumes that her patients identify with it.

“We can’t have the same conversation with every patient,” Attai says. “Every patient is different, and we need to talk to each of them differently.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.