WHEN SHE WAS DIAGNOSED with breast cancer in December 2014, Kate Pickert was already accustomed to poring over research and talking with experts in her role as a health care reporter for Time magazine. The skills she’d amassed on the job, such as gathering data and considering multiple perspectives, helped her become a better-informed patient.

“Having a better understanding of my disease helped me to have confidence in my treatment,” she says. “I think it did a lot to ease my anxiety.”

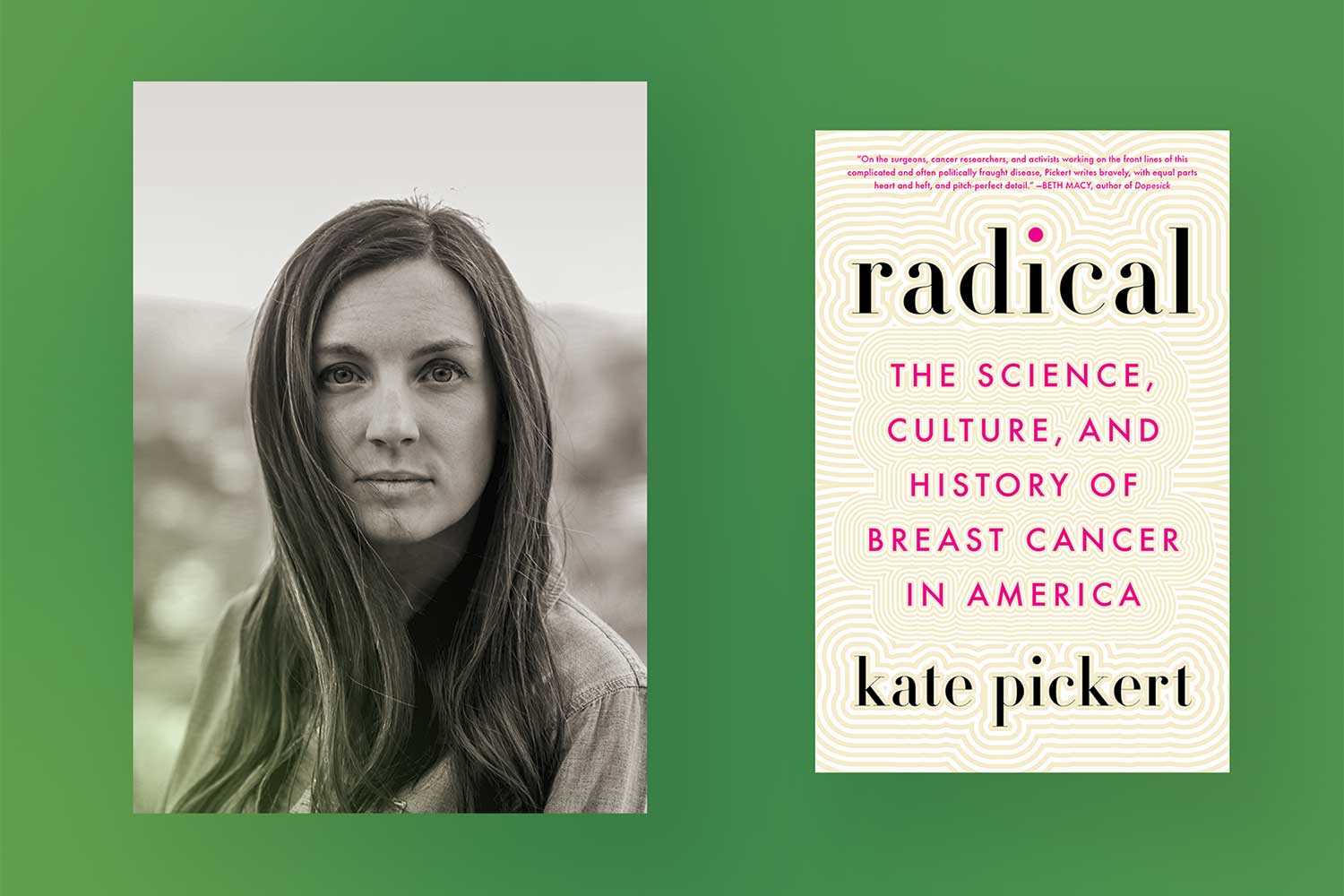

Pickert was 35 when she was diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer. Over the course of a year, she had a double mastectomy, 22 lymph nodes removed, chemotherapy, radiation and targeted therapy. She soon decided she would write a book that would include perspectives from patients, survivors, advocates, and the researchers and clinicians who brought current treatments to the fore.

Talk More About the Book

Through Sept. 18, we will be discussing Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America in our online book group.

The fruit of those efforts, Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America, was published in October 2019. As a reporter used to focusing on other people’s points of view in her stories, Pickert felt most apprehensive about including her own perspective in the book. “Usually, I try to stay out of the way of the story,” she says, noting that distance helps maintain a level of objectivity.

Pickert’s personal experiences add depth to her reporting. She writes about observing a mastectomy from the operating room at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles while standing alongside one of the surgeons who had performed her own surgery. In another part of the book, she describes a tour of Genentech’s packaging facility. The San Francisco-based pharmaceutical company manufactures Herceptin (trastuzumab), the drug that has helped increased survival rates for people with HER2-positive breast cancer, like Pickert.

“This is what journalism is. [It’s] largely getting access to places and people that the general public cannot,” Pickert notes. “Our job is to go to these places and talk to these people and bring back what we learned for the audience.”

Pickert, now a journalism professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, spoke with Cancer Today about what she learned from her experiences as a patient and while writing the book.

CT: What surprised you as you gathered information for the book?

PICKERT: I write about health, but I don’t have a degree in a scientific field. So, like a lot of people, I imagined science unfolding in this orderly and logical way. The thing that surprised me the most is how many assumptions we’ve made about cancer and breast cancer over the years that we later realized were wrong. That gives me some perspective on the way we look at breast cancer and breast cancer treatment now, and how in a few decades, we may look back in wonderment that we viewed the disease in the way we do today. That perspective is always changing. Science can be messy and slow, but it’s also miraculous.

CT: You interviewed a lot of people for this book. Which stories stick with you?

PICKERT: I think about many of the women who are affected by this cancer who shared their stories with me. The women in the book have had a range of experiences. Some are women who would ultimately die of breast cancer, other women overcame it, and others are still living it and in the middle of it. I wanted to convey the spectrum of the breast cancer experience. I was a breast cancer patient myself, but I am just one person with one experience. It was very important to me to not portray my experience as typical.

CT: You write about metastatic disease in the book. Given your cancer history, was that difficult?

PICKERT: Talking with people with metastatic disease was necessary to provide a full perspective. As a journalist, I feel a tremendous responsibility to tell the story of these metastatic patients because, in the world of breast cancer, they are very rarely written about. Their disease is not well understood. I knew I had to talk to people with metastatic disease and to do as much as I could to learn about metastatic breast cancer.

CT: You portray some upsides and downsides of the advocacy movement, including the pink ribbon movement. What are your thoughts on the pink ribbon?

PICKERT: On one hand, the pink ribbon has helped destigmatize the disease, but it also flattens the breast cancer experience into this generic narrative that makes it seem like it is the same for everyone. I also think the breast cancer advocacy that is most visible, and this includes the pink ribbon, can really obscure the complexities of the disease.

I think women diagnosed with breast cancer are very likely to go into the treatment experience with a lot of misconceptions about the disease, about what treatment will be like, and about the likelihood of survival. We haven’t really done a good job of educating American women about some of the complexities of breast cancer beyond the pink ribbon.

CT: How are you feeling?

PICKERT: I am very fortunate to have been doing well since I finished treatment. Typically, the type of breast cancer that I have recurs within a couple of years, if it does come back—unlike a hormone-driven cancer that can recur many years or decades later. It’s been more than five years since my diagnosis. That said, I still think about recurrence every day. It is an increasingly remote possibility, but I know it’s still a possibility.

CT: Is there anything you’d like to share with people who are diagnosed with cancer?

PICKERT: I try to let newly diagnosed people know that they have the ability, to some degree, to shape their own experience. Sometimes patients have different concerns than their doctors. You have to tell them what you are concerned about. You have to share your priorities.

I also encourage everyone to get a second opinion. If you aren’t close to a big academic medical center, you can get second opinions remotely or via Skype. I am a big fan of getting as much information about your disease as possible.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.