OVER THE PAST 14 years, prostate cancer survivor Westley Sholes has had many reasons to feel proud. But there’s one experience, he says, that tops them all.

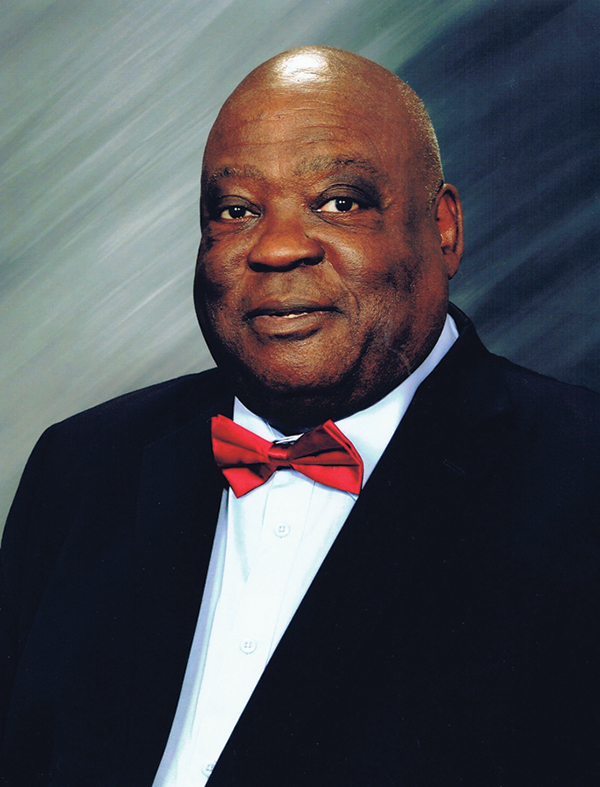

Westley Shoals

It was 2005, and Sholes had just testified before the California State Senate in support of a bill that would permanently protect coverage of prostate cancer treatment for low-income uninsured and underinsured Californians. (The effort ultimately succeeded—led by the group Sholes helped found, the California Prostate Cancer Coalition.) As he walked down the hallway, a woman who had recently lost her husband to prostate cancer approached him and said, “Even though [the bill] couldn’t save [my husband], he was highly appreciative of the work you are doing.”

Looking back, says Sholes, 72, “I can’t think of an entire moment in my life that had greater satisfaction.”

Sholes, who was diagnosed with prostate cancer at 57, believes his awareness of his high risk for developing the disease was a key factor in his early stage diagnosis. His father had died of the disease in 1992. Moreover, Sholes knew that African-American men have the highest incidence of prostate cancer in the U.S. and that they are more than twice as likely as white men to die of it. After his surgery, he decided to make sure that other men in his community also knew about the risk they faced.

Not knowing where to begin, Sholes, who lives in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif., searched the internet. He found an African-American prostate cancer survivor named Bob Samuels in Tampa, Fla., who put Sholes in contact with a small group of people in California who were also interested in working on prostate cancer issues. Volunteering, Sholes soon learned, “begins with one person talking to somebody.” Less than two years later, in 1998, Sholes and his new friends founded the California Prostate Cancer Coalition.

Not all of Sholes’ volunteer work involves lofty policy discussions. Some days, he simply spends time on the phone talking with men who have been newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, or giving advice to those who have advanced disease. After Sholes’ own diagnosis, he says, “I felt the need to give back and I had the time to do that. And as I got more and more into it, my interest grew.”

His advice to others who want to volunteer: “Find out what it is you want to do and then start searching for information, start talking to people, look online, talk to your doctor. Then one thing leads to another. … The main thing is motivation—and a get-off-your-butt-and-do-something attitude.

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.