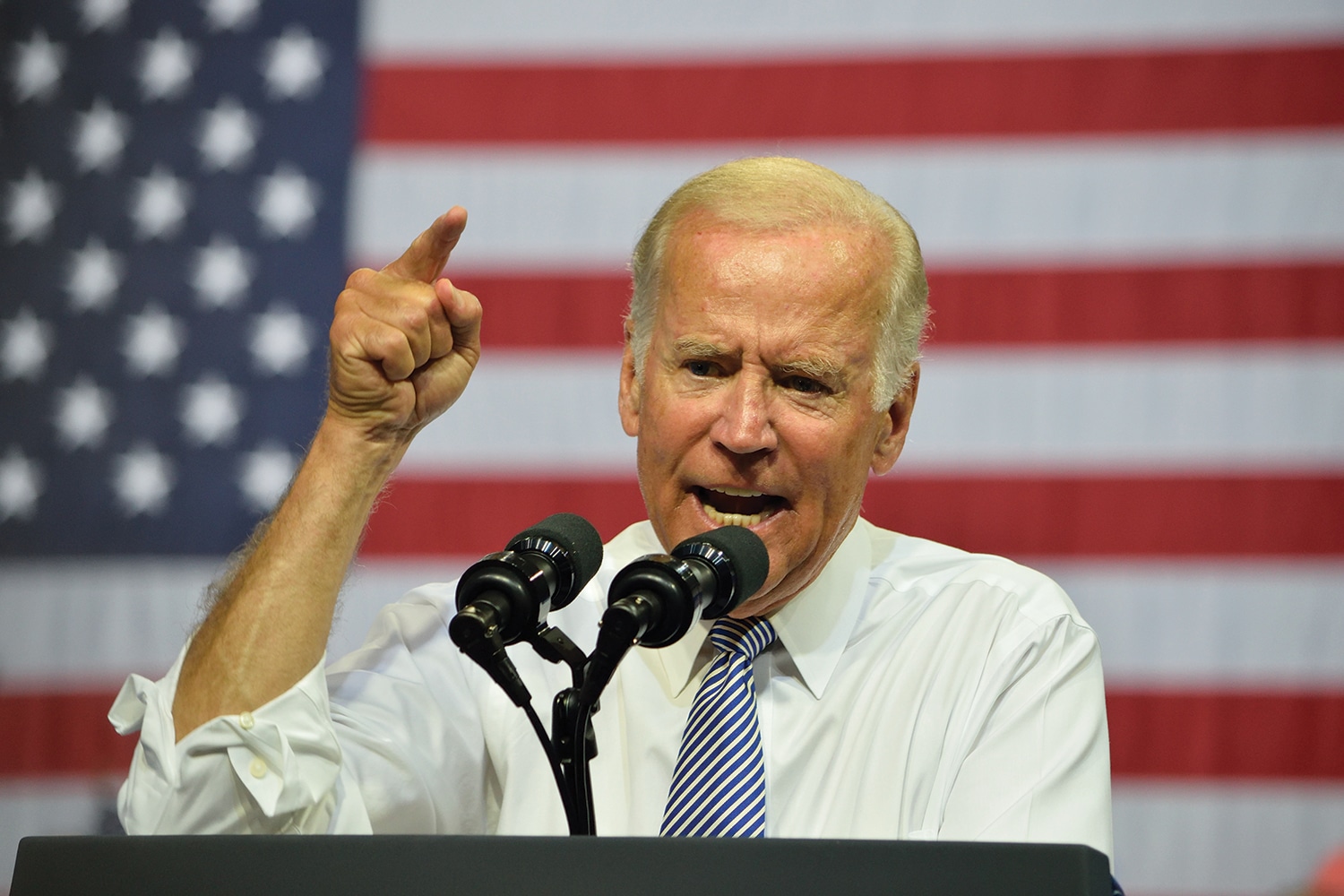

When Beau Biden died from brain cancer in May 2015, his father, then-U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, turned grief into action. He spent his last year in office helping to develop the Cancer Moonshot, a U.S. government initiative designed to accelerate the pace of cancer drug development.

In December 2016, the Cancer Moonshot became law as part of the 21st Century Cures Act. The law authorizes $6.3 billion to be spent over 10 years on research into treatments and patient care for a variety of diseases. Through the Moonshot, 28.6 percent of the total amount, or $1.8 billion, will go to research focused on cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment, including cancer vaccines and immunotherapies.

Nearly 1.7 million people in the U.S. will be diagnosed with cancer and more than 600,000 will die of the disease in 2017, according to American Cancer Society estimates. Kim Thiboldeaux, CEO of the Cancer Support Community, based in Washington, D.C., is one of the advocates who have commended the new law for drawing attention to cancer patients. Thiboldeaux calls the Cures Act a “win for patients, future and current.”

In response to recommendations from a panel of cancer experts who met in 2016, the Cures Act focuses more attention on patient-reported outcomes. For example, one of the act’s provisions requires the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to report on patient experience data associated with a drug’s approval. Shelley Fuld Nasso, CEO at the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) in Silver Spring, Maryland, thinks the new requirement will help doctors and patients learn more about the short- and long-term side effects cancer patients experience. She hopes it will also encourage scientists to develop less toxic treatments.

Medical oncologist Nancy Davidson, executive director of oncology for the Fred Hutchinson/University of Washington Cancer Consortium in Seattle and president of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, says she is excited about the cancer research areas supported in the Cures Act. Davidson is also president of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), which publishes Cancer Today. “We are now reaping the benefits of yesterday’s science with today’s treatments,” she says. “It’s new findings from research that will ultimately inform the treatments of tomorrow.”

In January 2017, the FDA implemented part of the new law by establishing its Oncology Center of Excellence. The Center will focus on identifying new and better ways to get effective drugs to cancer patients. However, Fuld Nasso cautions patients not to expect to see changes overnight. “The Moonshot funding accelerates the science, but that’s not going to translate to new cures immediately.” The journey from laboratory findings to patient benefit will still take years, she says, hopefully just not as many.

Some advocates and doctors say the Cures Act will financially benefit pharmaceutical companies at the expense of patient safety, in part by loosening regulations. Previously, the FDA could base approvals only on findings from clinical trials. Under the Cures Act, it can also take into account “real-world evidence,” such as safety reports and observational studies, when considering requests for expanded approvals of a drug. Critics say they fear this could lead to approvals of treatments that haven’t been thoroughly investigated. However, both Fuld Nasso and Davidson say they do not expect the law to change the FDA’s patient-centered approach or the way it weighs effectiveness against safety when evaluating new cancer drugs.

The NCCS, the AACR and other cancer organizations say they intend to track implementation of the law under the new administration. “The 21st Century Cures Act is wonderful,” but we still need to do more, says Davidson. “We need to be in front of our legislators to remind them that cancer is a huge problem in the United States and around the globe.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.