“GOD, HELP ME. I don’t want to die fat,” Lela Satterfield prayed.

It was 2009, a year after the medically obese music teacher in Oceanside, California, had been diagnosed with stage I breast cancer. Satterfield had weighed about 235 pounds before a lumpectomy, chemotherapy and radiation therapy wiped out her tumor, but she came out of the treatment 30 pounds heavier. She soon changed her eating habits and lost 40 pounds—only to start gaining it back. “I panicked,” she says of regaining weight.

Satterfield is among an increasing number of cancer patients who are obese at diagnosis. Indeed, weight plays a role in greater cancer risk. America’s obesity epidemic has become a crisis in cancer care, with the American Institute for Cancer Research, a cancer prevention nonprofit, estimating that more than 120,000 people in the U.S. each year develop one of a variety of cancers associated with excess body weight. Two decades worth of research have shown a litany of negative consequences for survivors of certain cancers who carry extra weight, such as worse survival rates, increased risk of cancer recurrence and more side effects.

The good news is that an unprecedented effort is underway to improve care and outcomes for overweight and obese cancer patients. More than 2,000 papers on obesity and cancer have appeared in scientific journals in recent decades, which is helping doctors better understand the obesity-cancer link. In May, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) released a guide to help oncologists manage obesity-related challenges in patients.

More than a year after the American Medical Association recognized obesity as a disease in its own right, the verdict is still out on whether losing weight reduces the risk of recurrence or death from cancer for obese cancer patients. But now there is a better understanding about what obese cancer survivors and their doctors can do to improve survivors’ lives, says Jennifer Ligibel, a medical oncologist and researcher at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“I tell my patients early on that there’s more to fighting cancer than medication,” she says.

Extra Weight Equals Extra Risks

In 1980, only about one in seven American adults were obese. Today, one in three are obese, meaning their body mass index, or BMI, is 30 or higher. (A normal-weight BMI is in the range of 18.5 to 24.9; 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight.) By these benchmarks, an obese person would include a 5-foot-5-inch woman who weighs at least 180 pounds or a 5-foot-11-inch man who tips the scales at 215 pounds or more.

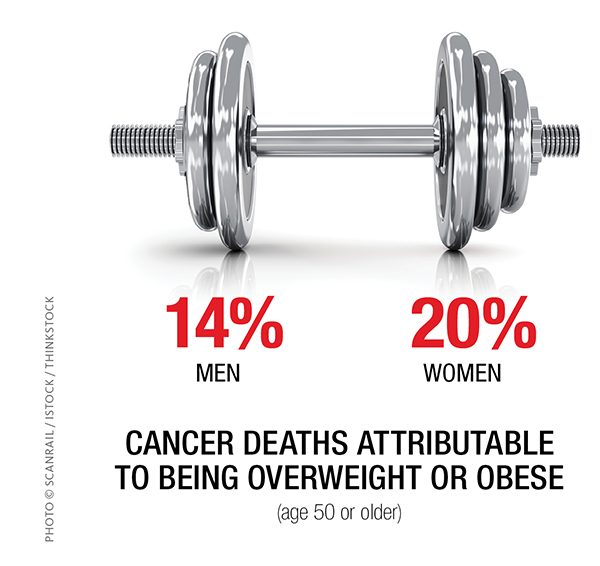

There are nearly 14 million cancer survivors in the U.S., and for many cancers, studies indicate more than two-thirds of those diagnosed are overweight or obese. In addition, researchers from the American Cancer Society (ACS) came to an alarming conclusion in 2003: The condition of being overweight or obese may account for up to 14 percent of cancer deaths in men and 20 percent in women 50 or older.

Obesity correlates with some cancer types more than others. And the increased risk can be substantial: According to an analysis of more than 80 breast cancer studies reported in the Annals of Oncology online on April 27, 2014, obese women diagnosed with breast cancer are 35 percent more likely than normal-weight women to die of their cancer and 41 percent more likely to die of any cause. Another study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2006 found a 38 percent increased risk of cancer recurrence or a new cancer among very obese colon cancer survivors compared with normal-weight survivors. Very obese is defined as having a BMI of 35 or higher.

“A lot of patients are not aware that obesity is a risk factor for recurrence,” Ligibel says. “Even oncologists haven’t paid much attention in the past to a patient’s weight, despite the association between obesity and worse cancer-related outcomes.”

Some of those worse outcomes extend beyond the cancer itself to the side effects of the disease or its treatment. Obese breast cancer survivors are at greater risk for lymphedema, a painful swelling that can occur after breast surgery. Incontinence is more likely and more severe in obese prostate cancer survivors. And obese patients with various cancers are at increased risk of blood clots during chemotherapy, cancer-related fatigue, diminished quality of life and surgical complications such as infection.

Adults and children carrying extra pounds face a higher risk of a cancer diagnosis.

More than 78 million U.S. adults—about 35 percent—are obese, based on the latest statistics from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). One-third are overweight.

Photo © Galdzer / istock

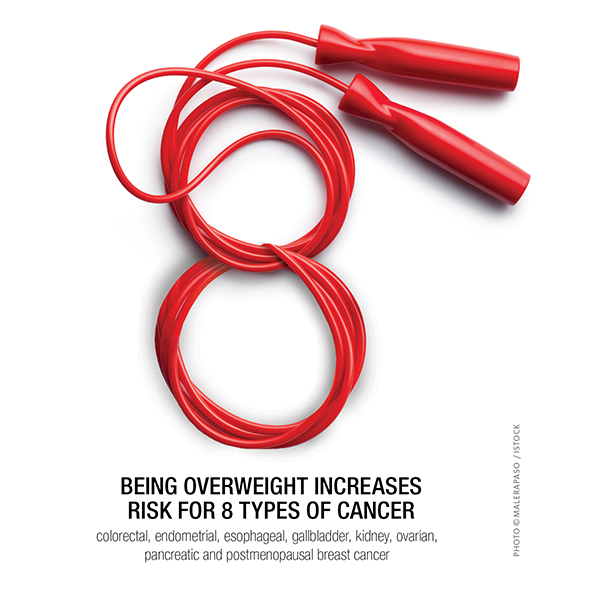

According to the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR), being overweight or obese increases risk for eight cancers: colorectal, endometrial, esophageal, gallbladder, kidney, ovarian, pancreatic and postmenopausal breast cancer. The greatest association is observed in endometrial cancer, for which half of all diagnoses are linked to excess body fat.

Research also suggests being an obese child increases risk for some cancers later in life, putting an estimated 12.5 million obese American children and teens at risk, according to 2012 CDC data.

Yet fewer than half of adult Americans— 48 percent—know that obesity increases cancer risk, according to a 2013 AICR survey.

For people who are overweight or obese, the American Cancer Society recommends losing even a small amount of weight. The organization’s cancer prevention guidelines also recommend that:

- People eat at least 2½ cups of vegetables and fruits a day, limit processed and red meats, and replace refined grain products with those made with whole grains.

- Adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity each week.

- Children and teens get at least one hour of moderate or vigorous activity each day, with vigorous activity at least three days a week.

Why Weight Adds Risk

As study after study showed that cancer recurs or progresses more often in obese patients, researchers started to ask why. What they’ve found is that excess body fat produces more estrogen and more growth factors, and people who are obese often have more insulin and more inflammation—all factors associated with cancer’s development and growth.

Having an obesity-related condition such as diabetes, heart disease or stroke also influences a patient’s survival odds, says Jeffrey Meyerhardt, a gastrointestinal oncologist and the clinical director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber. “Even if people are doing well from their cancer, you can’t neglect these other health issues,” he says.

But the most startling reason obese people with cancer may have lower survival rates than their normal-weight peers is that as many as 40 percent received too little chemotherapy. In the past, oncologists would often cap a chemo dose at a certain amount regardless of a patient’s weight out of fear that larger doses would be too toxic. Yet studies show obese patients treated with full doses based on their weight have no more side effects from chemotherapy than healthy-weight patients.

“Underdosing may in part explain why obese patients have a higher risk of recurrence and mortality,” says Gary Lyman, a medical oncologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and a co-director of the Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research.

In 2012, ASCO released guidelines for oncologists that warned against dose-capping and advised them to use actual body weight to calculate chemo doses for obese patients. Lyman led the panel that wrote the guidelines and says many institutions that were dose-capping for obese patients have eliminated the practice. “There are legitimate reasons to cut back on chemotherapy strength, such as heart disease or kidney disease,” he says. “But obesity is not one of them.”

A year before the guidelines’ release, Tracy Smith from Durham, North Carolina, began chemotherapy for stage III breast cancer. She received full doses based on her weight, which at 310 pounds put her in the obese category.

Smith’s doctor told her she’d be getting a high dose of the toxic drugs. “It didn’t worry me,” she says, recalling bouts of mild nausea and shortness of breath but nothing severe. “She knew to base my chemo dose on my body weight, and I’m forever grateful for that.” Smith, 47, shows no signs of cancer and works as an aide for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Use these resources to lose weight and improve your health.

ON THE WEB

Managing Your Weight After a Cancer Diagnosis

A downloadable booklet for cancer survivors and families from the American Society of Clinical Oncology

Choose My Plate

A U.S. Department of Agriculture website that offers weight management tips and SuperTracker, an interactive food and exercise tracker

ON A SMARTPHONE

MapMyFitness

An application that allows you to plan, track and share your workouts using your GPS-enabled mobile device

MyFitnessPal

A calorie counter and food tracker that includes more than 4 million foods

IN PERSON

Livestrong at the YMCA

A 12-week, small-group program to help adult cancer survivors become more physically active

American College of Sports Medicine ProFinder

A listing of certified cancer exercise trainers

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

A national database of registered dietitians and nutritionists, many of whom specialize in cancer

Taking Steps to Better Health

At M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, BMI is measured in every breast cancer patient, says breast medical oncologist Abenaa Brewster. She talks to her obese patients about healthy eating, portion control and exercise. “But it’s probably inadequate. Doctors need some help,” she says.

An ASCO guide for oncologists released in 2014 offers that assistance. It recommends the following formula for obese patients: Eat fewer calories than the body needs to maintain weight, get more exercise and learn the skills to change unhealthy behaviors. If sticking to these lifestyle changes doesn’t result in weight loss, obese survivors should talk to their primary care doctor about whether bariatric surgery is an option, says Ligibel, who led the panel that wrote the guide.

While the ASCO guide stops short of recommending a certain amount of exercise for obese survivors, the ACS and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) advise that all survivors gradually work up to at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise—for example, brisk walking or water aerobics—each week. Less than a third of survivors actually meet that goal.

Being overweight increases risks for eight types of cancer: colorectal, endometrial, esophageal, gallbladder, kidney, ovarian, pancreatic and postmenopausal breast cancer. Photo © Malerapaso / iStock

Kathryn Schmitz, an exercise physiologist at the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center in Philadelphia, thinks she knows why. For some obese survivors, the hope for a longer life is not enough inspiration to overhaul their diet and start exercising. Being told they’ll feel better in the short-term is a stronger motivator, says Schmitz. She was the lead author of the ACSM exercise guidelines for cancer survivors.

“It’s the more immediate chronic issues that make people want to change their behavior,” she says. “Being in pain right now, having lymphedema right now, being fatigued right now seems to be a better driver for people to actually do something.”

For those survivors who do exercise, it appears to pay off. Research suggests exercise can improve quality of life, lower the risk of lymphedema, lessen fatigue, improve body image, boost physical functioning and reduce depression. It might even cut the risk of recurrence and death in people with breast, prostate and colorectal cancers.

In the U.S., Canada and Australia, researchers are testing whether a three-year individualized exercise program among colon cancer survivors reduces the risk of recurrence and affects survival, quality of life and physical fitness. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Schmitz is conducting the WISER Survivor study in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. She and her colleagues want to find out whether a calorie-restricted diet plus exercise works better than either alone in lessening lymphedema symptoms and reducing the hormonal and other biologic factors tied to breast cancer recurrence.

Benefits Beyond Cancer

One big unknown still remains in the quest to help obese cancer survivors: Despite the potential benefits of exercise, evidence currently doesn’t exist to say unequivocally that weight loss itself helps survivors live longer or free from recurrence.

But Brewster says survivors should think beyond cancer: There is no question that losing weight can lower a survivor’s risk for other leading diseases. Research has shown that just a 5 percent sustained weight loss can lower a person’s risk of diabetes and heart disease, the nation’s No. 1 killer. For a 200-pound woman, that’s a weight loss of just 10 pounds.

Back in California, Satterfield has participated in the largest weight loss trial in cancer survivors to date. Nearly 700 breast cancer survivors are taking part in the study, called ENERGY (Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You). The study combines intense behavioral counseling, calorie restriction and an hour a day of exercise.

“There’s a world of difference between knowing what you’re supposed to do and having the skills to do it,” says study leader Cheryl Rock, a nutrition scientist at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center. That’s why Rock’s team is teaching participants to plan meals, set goals and cope with temptations.

The technique that works best for Satterfield is writing down everything she eats along with the number of calories, something she still does today nearly four years after starting the study. Today, her weight is at 180 pounds—down from her peak of 265 at the end of treatment—and dropping. “I learned to be accountable to myself for what I ate. I’m not eating mindlessly anymore,” she says.

By next May, Rock expects to have results on how weight loss affects quality of life, fatigue and depression, as well as joint and muscle pain and medical conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure. She and her co-investigators also hope to someday test whether weight loss has an impact on breast cancer recurrence.

Regardless of whether Satterfield’s weight loss staves off a recurrence, doctors say the 65-year-old already has lowered her risk of heart disease. She no longer needs medication to control her blood pressure and delights in being able to get on the floor to play with her two granddaughters. Her doctors say if she continues to lose weight, she may no longer need medication to keep her diabetes in check.

But getting her energy back has meant the most. “I still want to lose 45 pounds,” she says. “And I’m going to. It’s been slow but steady.”

Cancer Today magazine is free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S. Subscribe here to receive four issues per year.